Thank you, Mr. Chairman. Chaverim, the topic I am going to speak on is very dear and close to my heart, for the topic is Yiddish theatre. As most of you know, I was born into and bred by the Yiddish theatre. Its demise has often caused me much grief and sadness, and when I was asked to speak on this subject, I readily accepted even though I am not a speaker per se. However, I am going to try in this short talk to give you a picture of the rise and fall as it were of the Yiddish theatre. The characteristic changes in theatre are directly attributed to the changes in its directors. It can lead its art to the highest of cultural levels or drag it down to the gutter. It is particularly difficult to document the history of Jewish directorship. In the beginning, Jewish theatre consisted of the mechanics of learning a script, but not really acting until the night of the performance. Rehearsals were strictly dry and mechanical. It is interesting to note that this attitude prevailed with many of the Jewish actors until the very end of their career. Scripts or plays had no, or very little directions for the director to follow. Sholem Aleichem once wrote that “nothing has become so frozen as the Yiddish theatre, and that no progress has been made in it since the Purim Shpielers or the Bretel Singers.” Chaverim, that is not entirely true for we have seen expressionistic experiments where one actor would read a whole play such as Maurice Siegler doing the entire play of “Akaidos itzchok”, or Maurice Schwartz doing the entire play of the “Dybbuk" when they went on tours as a one-man play. Jewish theatre has gone from the gesture-type of acting, where one actor sits on the knee of another and makes gestures while the other speaks – a sort of “Charlie McCarthy” type to a three-stage theatre such as the New York Art Theatre.

I guess you might say that the first real theatre was opened in 1903, especially built and was called the Grand Theatre, where such actors as Sophie Karp, Berl Bernstein, Maurice Finkel, Joseph Lateiner, Jacob P. Adler et al. played. A few other theatres came along later [from] 1909 to 1912. Theatre really began to prosper after World War I, and a few more theatres opened up such as the Public Theatre, Art Theatre and so on. At one time in and around New York, there were as many as ten permanent theatres, and [it] soon became known as the center of Yiddish theatre in the Americas. Other cities became known for Yiddish theatre [were] Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, Minnesota, St. Paul, where these traveling troupes went. Then Canada became a place to play, such as Toronto, Montreal, Winnipeg, where troupes remained for a full season. It was considered that only second-class troupes came to Canada, but in my own opinion, I think that was wrong, for Boris Shumsky who played two seasons in Winnipeg was no second-class actor. Madame Karaleva was one of the finest; my own parents [were] another example of the better class of actors. In South America, Jewish theatre began to grow, and such actors as Finkel and Blank did much to make a fine theatre outlet. In 1902 Karl Gutenberg and wife, Boris Auerbach and wife did such plays at Shulamis, but it wasn’t until 1906 that a permanent troupe remained in Buenos Aires. Jewish theatre in those days was a "sometimes thing", until Boris Thomashevsky started to play professional theatre during weekdays in 1924. Their repertoire was Gordin, Goldfaden, Shakespeare (Siegmund Feinman did Othello), Lateiner, Zolotarevsky. However, printed plays in the olden days were unknown. Troupes would travel and engage a playwright who would not only write the plays, but also the scripts, and prior to that there was little order and a lot of dialogue off the cuff -- “arble prose” it was known. I guess the first play writer to draw American life into Jewish plays was Joseph Lateiner when he wrote “The Immigration to America”. But the real production-line playwriting began in 1886 when Mogulesko brought a European troupe in with David Kessler, Leon Blank, [and] Bina Abramovitch. Even the importation of Goldfaden didn’t do much to change this situation. Hear Sydney Swerdlow talk about famed Yiddish playwright Jacob Gordin, and his impact on the Yiddish theatre.

We see a tremendous surge towards realism in 1929-30, especially in Europe where repertory theatre [was] still popular with such performances as Shakespeare’s “King Lear”, Goldfaden’s “Shulamis” or "Bar kochba", Sholem Aleichem's “Tevye”. It seemed that only in America, Yiddish theatre was satisfied to remain stagnant, satisfied with the status quo as it were. Stars still ruled the roost, and they guarded their position with jealousy and zest. There were those actors who tried to keep theatre on a high level, but it seemed that the lust for the dollar prevailed. There were actors like Kessler, Thomashevsky etc, etc. But the intelligent theatre-goer knew that his cravings for intelligence were not fulfilled, and the better actors knew that also. Maurice Schwartz and his repertory Art Theatre strove for better plays by better writers. Now, his rendition of these plays and the playwrights became famous, as for example I. Singer for the “Yoshe Kalb" in 1933; ” Leivick's “Shmates” in 1921, etc., etc. Now others were very active in trying to uphold the image of the Jewish theatre, e.g. Rudolph Schildkraut's theatre opened in 1925. Other little professional theatres, under the directorship of such as Jacob Mestel, Avrom Brekher, etc. where they did not only Jewish plays, but plays translated from English with a social message, such as Sinclair Lewis' “It Can’t Happen Here”, Clifford Odets' “Wake Up and Conquer”. And then in 1925, Artef was born with a performance of “Beym toyer”. Artef allowed its actors a lot of freedom of movement and expression. Artef under the directorship of Jacob Mestel was a sort of a proving ground, an experimental theatre. But theatre is only as strong as its weakest link, and Jewish theatre gave way to the cheap sensationalism of cheap Broadway melodramas, cheap films and cheap radio buffoonery. The actor, as well as the times, were a great deal responsible for the decline in Yiddish theatre. The first actors were very seldom intellectuals. They were shop workers who could barely read and write. Now even to this day, one Jewish actress, I know one who cannot read Yiddish and has therefore never read a Jewish book. There was one actor in particular [who] I know who couldn’t even read or write in any language. So that the intellectual level of the Yiddish actor was in the beginning very low. I don’t want to leave the impression that there were not any well-read and learned actors, because there were but they were not in the majority. It was these well-learned people [who] strove for better theatre. As a matter of fact, as early as 1908 intellectuals were drafted into the Yiddish theatre, as for example the Hirshbein troupe, doing literary work came into mode. In the main, Yiddish theatre adopted the star system, where the star ruled supreme and the play centered around him. This of course was a mimic from the English stage. If Yiddish theatre did achieve a certain prominence, it was directly due to the fact that the Yiddish stage was blessed with excellent actors who even were asked to appear in English stage such as Adler, Kessler, Bertha Kalich, Thomashevsky, Ben Ami, Schwartz, Paul Muni, Stella Adler, Molly Picon, Buloff, but only [a] few managed to make their mark on the English stage. Very rarely do we find in the Yiddish theatre a director per se, but usually the star is also the director, and in that way he would omit any scene [that] did not glorify his characterization, or scenes would be added to the script that helped him come out on top with no regard for the mechanics of the script. Songs both single and duets were inserted into the script where they are not really called for, but just to let the actors with somewhat decent voices air their talent. In short, too little respect [was] given the playwright until Gordin forced this respect and consideration for reality. As mentioned before, the Purim Shpielers never had scripts. They just learned lines from each other from a certain plan, and that is the way it all started, with one actor would even prompt[ing] another actor right on stage. It was Goldfaden who first instituted rehearsals, and even then an actor who had already played a certain role, very seldom came to rehearsals when he was called to do that same part again. Dress rehearsals were then not heard of, and that situation prevailed even to the end. No general analyzation of characters were ever made, and each actor played his part according to his own understanding, and because there were no studies in characterization, very often there was a clash of personalities. Now no corrective rehearsals were ever held (except for very rare instances), even though the play suffered and was a flop. Scenery was, of course, in the beginning none existent. Actors would very often announce, “Now I’m in the garden”, etc., etc., and it wasn’t until Goldfaden that any kind of scenery was used, and then of course, it was on a primitive plane. But little by little scenery became more in demand, and because the demand became more sophisticated, that included props to a point were Maurice Schwartz use a real horse and wagon in “Tevye der milkhiger”. Scenery was either built or borrowed from non-Yiddish theatres. Furniture became more realistic, that is, they were more in keeping with the scenery. But realism only went to a certain point. For religious purposes, realism was often set aside. For example, a cross was seldom brought on the Jewish stage. The character never, never smoked a cigarette on stage on the Shabbos. Even in the Art Theatre on the week of Passover, matzos were eaten on stage instead of bread. But later realism took on a more realistic form. Real water was used in rain scenes, real blood was used on stage as I mentioned before, for example in Gordin’s play “Der vilder mensh” of the murder and suicide scene. In a poor home, a soiled towel was used to depict poverty. Maurice Schwartz even used a live monkey in the play, “The Kishufmakherin”. [24'15"] While there are about a ten thousand plays written in America and read by all theatre builders, but only a hundred are considered, about twenty-five actually performed and maybe two are a hit. Now you must remember and understand that the Jewish market is much smaller, so that the yearly output of Jewish plays [was] very small, which means if no Jewish plays are forthcoming the Jewish theatre had to resort to doing the old repertoire. The playwright before the Art Theatre and before Artef was too little acquainted with theatrical technique and many plays were actually not playable. This was especially true amongst the new playwrights. The most successful playwrights are the ones who are theatre people: Goldfaden, Gordin, Hirshbein, Kobrin. Realism in theatre as professed by Stanislavski has, however, been debated whether it was right to ask the actor to leave his own personality and take on another, or was rather the interpretation of a character by the actor...which reflected his ability and the art? The functions of the play or a script was to give substance; but to give it life and to give it meaning that is the true function of the actor. To achieve a semblance of realism, one must choose his character not unlike the live character. For example, if you are producing the life of Napoleon you would certainly not choose a tall, slender man, but a short and stocky man etc. In this facet the English stage and film ruled supreme. They had a vast field in which to choose from. In many cases, they would even match up the voice. But in the Yiddish theatre, this vast field of choice did not exist and with the star system, the field of choice was even more limited, and also with the English Theatre and film the potential audience was so large, that they had writers write a play around the star, whereas the Yiddish theatre with its limited audience could not afford this luxury. I have spoken till now about the growth of the Yiddish theatre, its failures, its successes. The tragedy is that the Yiddish theatre was barely Bar Mitzvah, just as it became a man, it died; at least in the North Americas. It is true [that] from time to time we do see some Jewish theatre with strange names, but theatre amongst the Jews as such is dead. It is interesting to many, [so] why did it happen? How could the Yiddish theatre that had such wonderful names attached to it disappear? I shall now try to give you my version of the autopsy. I say my version, because it seems to me that if you speak to a dozen knowledgeable persons, you would have a dozen different versions of the autopsy. You will recall that I spoke of the position of the actors, how jealously they guarded it. The Hebrew Actors Union helped the actors guard that position. It was in the strictest word a "closed shop". Its members knew or felt that the only way they could guard their position was to have a closed shop. If you were an actor with talent, that alone was not sufficient to get you into the union. Now because the theatre managers didn’t want any trouble with the union, they went along with them. It is true that in many cases non-union members played with a cast that were union members, but they suffered in as much as the better parts were not given them, even if they were more qualified and talented in the features and voice, but while they played with the union cast, they paid union dues. A person who wanted to go on stage found all kinds of obstacles, and mainly from the actors. You see, to get into the union, a committee of actors sat in judgment of you; whether or not they are going to accept you. If their position as an actor was not threatened, you were in, but if they thought that because of your talent, their own position would be in jeopardy, you were out. It is rumored that Maurice Schwartz had trouble getting into the union and because of the great fuss the Forward made. The union was forced to take him in, but then Schwartz had money and could fight them. But to the good actor who had no money – well? It was a requirement of the union that before he was considered for membership, an actor had to play the provinces for three years. That was because no actors wanted to leave his home, so that was one way they could send these troupes to the provinces. You might call it blackmail, but even then you were not assured that you would get into the union. My own parents were not union members because they were not permitted to join. Many reasons were given, but none held water. I know for a fact that an actress, Celia Pearson, who was a third-rater but a union member, voted against my father who was acclaimed one of the finest character actors on the Jewish stage. All this held the Jewish theatre back. New blood was not permitted to infiltrate, and so theatre began to stand still. Women who were fat and forty played soubrettes. Sally Josephson was forty-five when she played buff comediennes. Mrs. Meyerovitch was over fifty and weighed over two hundred pounds when she sang on stage “Ich vil zich shpilen”. This is the situation that prevailed in the late 1930s and early 1940s. I have heard that the famous Danny Kaye couldn’t get a job in New York in Jewish theatre. Now in his case it was a blessing in disguise. The children of Jewish actors did not follow in their parent’s footsteps because of the hardship in Yiddish theatre. My own parents kept me from entering into the Jewish theatre for that reason, although later in life I played many seasons with them, but because I was a Canadian and not an American where some of the action really was, I drifted further and further from the scene. I know of very few of the famous actors whose children did go on stage, that is the Jewish stage. Only a few come to my mind, for example, Luther Adler, Stella and Celia Adler, Hershel Bernardi and a few others, the son of Maurice Schwartz. Because new blood was not allowed to enter, the old blood became older and older and soon had to resort to type casting. Now how many plays are there where the lead is an elderly man or woman? Because of smaller audiences, writers, i.e. the newer writers, who received greater rewards by writing for the English stage....drifted to that field in which they busied themselves. The older authors soon died off and so the Jewish stage was left with the old repertoire and with old actors. Because of small audiences, the Jewish theatre changed plays as often as once a week. Seldom did a play run for more than two or three weeks. “Yoshe Kalb”, it’s true, ran for two years but how many plays do you have like “Yoshe Kalb”? “Khelmer khachamim ("The Wise Men of Chelm" -ed.)” ran, I believe for a few months, but mainly two or three weeks was the life a Jewish play. Actors became so set in their ways, and too often was a character portrayed without first studying the play and what was supposed to be handed down to the audience. Too often was a play miscast. Too often was a play done without a drop of interest of just what was the author trying to convey. Too often was a play written without rhyme or reason, and too often was a play underdirected and overplayed. Now I don’t want to leave the impression that all actors had this attitude. No, it is not true. The dedicated artist knew that progress must be maintained. Some took on parts not entirely in keeping with their own age, but on the other side of the scale. For example, as long as I can remember my own parents played character parts. When my father was thirty-five he played Reb Elie in “Shmates ("Rags" - ed.)”, a man of about eighty or so. The critics acclaimed it as one of the finest interpretations of Reb Elie that they had ever seen. Now, it’s much easier for a man of thirty-five to play a character of eighty, than it is for a man of fifty to be playing a boy of twenty or twenty-five, because you could always have the aid of makeup. A young man can act feeble, but a feeble man can not convincingly play a young man. I think another factor [that] contributed to the decline of the Yiddish theatre. In the early days, the actor was a sort of a person who surrounded himself by mystery. The actor kept to himself and truly enjoyed that aura of mystery that surrounded him. People came to see the actor because that was the only time they could see him. In Europe the Jewish actors even had their own jargon expressions that added to this air of mystery. For example, “Neskim” meant, “stop talking there is an outsider coming”, and so on and so on. Now this air of mystery lasted as late as the late 1920s. In Winnipeg, for example, the troupe that played a whole season, all the actors chipped in and bought a large car so that they could be by themselves. But then came the time when actors left that closed circle and began to mingle with the people. Soon greed overtook the actors, and the actor began off-season to go to the mountains where he made a fool of himself for a few bucks. That broke his shell of mystery. The people saw him as a plain man, instead of someone whom he would have to pay to go and see. He began to question the value of the actor whom he had seen for nothing while stuffing himself with food. And then also came a time of no money. Fifty-cent tickets in the balcony could not be sold. To charge two or three dollars for a ticket was almost unheard of. And the tougher it was in the theatre, the more the actor ran to the mountains. And the more he ran to the mountains, the tougher it was to get the audience to the theatre. Again, you must remember that there were still actors who refused to shame themselves. Schwartz never played the mountains. Ben Ami, Lazar Freed, Itzhok Swerdlow and many other well-known actors would not lower themselves to go back to the Purim Shpiel-type of acting. These were the people who truly pioneered in their profession, and made it last as long as it did. The Jewish resort hotels soon were nicknamed the Borscht Belt, and it was the Borscht Belt that contributed a great deal to the downfall of Jewish theatre. The smaller the audiences grew, the more desperate the Yiddish actor became, and in order to keep this small audience coming, they had to change the plays more often. Here in Toronto, in the late 1930s, we used to play two new shows a week and a Sunday concert. Now, I wonder if you can appreciate the amount of work that is involved to put on a new show. How then can you keep the standard of quality and also quantity? Something must suffer, and suffer it did. Audiences became smaller and smaller, until it became not profitable to play Yiddish theatre. Actors became totally involved in night clubs, [the] making of records with double meanings [such] as Jennie Goldstein, Mintz, and many others, Skulnik, and devoted [themselves] full-time [to] the Borscht Belt, telling dirty stories for overstuffed audiences until one by one they died off. The better actors of various troupes teamed together and tried to hang on, but the times were against them. While Yiddish theatre is not entirely dead, it is quivering. There are names, as I said before, that I know nothing of. They are strange to me, a new breed, and maybe if they change and not make the same mistakes, maybe, just maybe, Yiddish theatre can become the grandiose theatre that it once was.

Thank you.

Please visit an

exhibition about

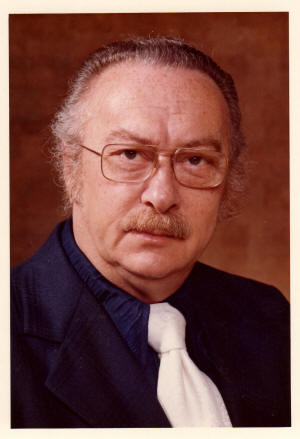

Sydney's parents, Yiddish actors Isaac and Adele, |

|

|