|

After years of strenuous effort, we finally realized the publication

of this memorial book, which commemorates the cherished name of our

hometown of Zambrów, the place of our birth, that was and is no

more.

Many ties have bound me all of my life

to this place, where I first saw the light of day. I left it as an

eleven-year-old boy. I have wandered a great deal since that time,

and I have absorbed both familiar and unfamiliar cultures. However,

I have never become estranged from the culture of my home town and

my mother's tongue. And when Zambrów was so tragically wiped off the

Jewish horizon, she rose spiritually anew before my eyes, and an

innermost impulse began to drive me on with an impelling force: to

arise and erect a spiritual memorial to Jewish Zambrów -- to give an

account of its history, those who were well-to-do (its balebatim2),

those Jews who toiled in her midst, her clerical and secular

elements, its learned men and the plain pious folks, her synagogues

and houses of study, its fraternities and institutions. And if it

would not be done at the present time, by the last generation of

Zembrovites, it would be unlikely that it would ever come to pass.

And so I took it upon myself, with a feeling of deep nostalgia, to

bring to realization this high purpose, this labor of love.

The memorial now has been erected. The

book has been published. But to my utmost regret, the enterprise has

not succeeded to its fullest desirable extent.

Zambrów was a small town. There is

practically nothing written about her in both Jewish and non-Jewish

literary writings. Also, our old home town is mentioned very

infrequently in the daily press. The city archives no longer exist,

and the part that did survive is not accessible to us. The

old-timers, as a live source of information, have passed on a long

time ago. Therefore, the one and only thing that remained for us to

do was to bend our head over whatever documents were available to

us, and from the casual remarks or allusions, out of brief

statements, try to restore sketchily the history of the town. And

who is to know how many facts disappeared from our view, and how

many personalities were forgotten by us? We could not resolve this

issue. Despite this, we established this initiative and the book was

published, in which the entire town passes before us as if in a

play. So, here and there, personalities and facts are perhaps

missing.

We turned to our countrymen, both the

young and the elderly, who retained things in their memory and are

wont to wield a pen. Very few responded to our proposal, apparently

because they did not believe that we would be able to accomplish our

task. Nevertheless, here is the book before you, the book that

describes the pathetic story of our Jewish Zambrów -- from her very

beginnings, up to her downfall.

What remained was for us to fashion

something about the history of the town from remnants and old

documents and from glimpses and minor observations, going from point

to point, item to item, to create an organized list of the history

of the town and its Jewish settlement. Despite this, we put together

a book about our Jewish Zambrów, from its inception to its

destruction.

We have written this book in both

languages, as our traditional literature had been written at one

time: The Holy Tongue (Hebrew) and

Ivri-Teitch (Yiddish) together, side by side. The reader will

have to make an effort to find the translation on the second side

but in this way we have done justice to our two languages: the

mother-language (Yiddish) and the father-language (Hebrew). We are

providing a short overview in English let the grandchildren of

those from Zambrów come to know something about the way of life of

their grandfathers and grandmothers. In a few places, we shortened

the text in one of the languages, or made use of only one of the two

languages. We took care to preserve the Zambrów Yiddish idiom3

as it was spoken in Zambrów.

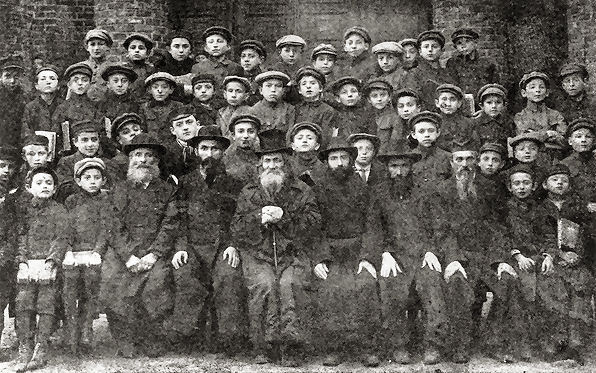

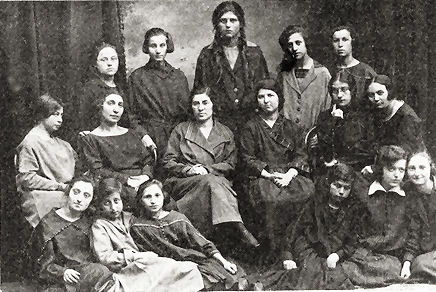

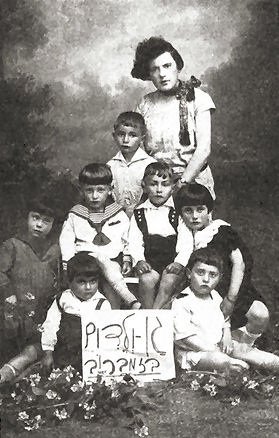

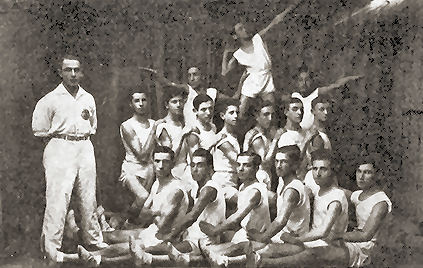

We have been able to provide the utmost

possible number of photographs that we had in our possession, if

only the were in a fairly good condition, as quite a great number of

them were regretfully in such a faded state that they would be unfit

to print. We have incorporated into the book more that two thousand

images of the Jewish Zambrów children, pupils of cheders and

folkshuls, with their rabbis and teachers. We incorporated

several hundred young people pictures of members of societies and

political parties, to the extent that we had them, not

differentiating between one party and the other. We have also given

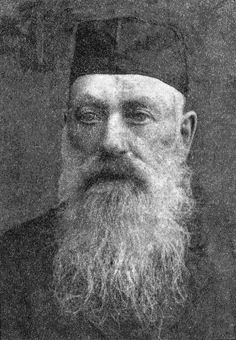

a series of portraits of singular personalities, portraits that are

in most cases the one and only thing that remained to remember them

by. We have included things about the ambience of the town this

freshens our memory and links us all the more to the cradle of our

childhood.

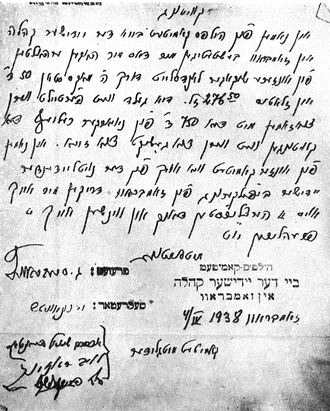

Regarding the eve of the destruction of

Zambrów and the Holocaust itself, we exclusively relied on primary

sources: from letters and eyewitness accounts. Regardless, if

certain details are not consistent, e.g. dates, etc., we have

included everything, just the way it was recalled.

The subject matter of the book can, in part, serve as an historical

source of Jewish life in Poland during the last century in general,

and of the last several decades in particular. To this end, we have

included Zambrów into the golden chain of Polish Jewry that was

exterminated by the German Amalek4

and its accomplices.

It is my responsibility here, to bring

to mind with gratitude and respect, those numbered few who helped me

with my work: My friend, Mendl Zibelman (son of R Israel-David,

Miami, Florida), adorned this book with his inspiring memories.

Professor Berl Mark (Warsaw). Chaim ben David (Moshe-Aharon, the

painters son, Detroit Israel). Zvi Zamir, Sender Seczkowsky

(Itcheh the Painters son, Tel Aviv), Joseph Srebrowicz (Tel Aviv),

Joseph Jerusalimsky (Ashkelon), The three Yitzhaks: Golda, Golombek

and Stupnik, and Moshe Levinsky smoking embers snatched from fire

and sword. And last, but not least: my beloved father and teacher,

Israel Levinsky ז"ל, who did not write just a little for the book,

but was not privileged to see it come to fruition. Chaim Zur (son of

Fyvel Zukrovich, Ramat HaKovesh) designed the cover of the book and

sketched a map of the town from memory.

Three Zambrów landslayt organizations contributed generously

to the material expenses for the book: The United Zembrover Society,

Inc. in New York, with its brother societies headed by our American

ambassador Joseph Savetsky, Isaac Rosen, Isaac Malinovich (who

gathered untold tens upon tens of pictures for the book), Eliezer

Pav and many others. With their broadness of heart and full and open

hands, the book became a reality.

Our countrymen in Argentina, led by the recently deceased Ch. Y.

Rudnik ז"ל, and to be mentioned for long life: Boaz Chmiel, Joseph

Krulewiecki, Jacob Stupnik, Crystal and many others also

contributed to the book, and from time to time offered us

encouragement.

"The Society of Zambrów in Israel" is

headed by the comrades: Zvi Zamir (Hershl Slowik), chairman; Zvi ben

Joseph (Hershl Konopiateh), secretary; Pinchas Kaplan, the sisters

Malka and Liebehcheh Greenberg, Leib Golombek, et al. They have all

done their beneficial share for the book.

At the end, our small Zambrów families:

In Mexico City, our friends Chaim Gorodzinsky, Isaac Rothberg and

others; and in France Esther Smolar-Shleven.

All those whom I have mentioned here,

and to those whom I have perhaps forgotten may they be designated

for good, and may they all bless themselves with this book, which

they cooperated in producing.

Yom-Tov Levinsky, Tel Aviv

|

A Word from the Zembrover Organization in

Israel |

The Pinkas5

of Zambrów is edited and partly written by our landsman Dr. Yom-Tov

Levinsky.

A full eight years have gone by since

we decided to publish a Yizkor Book about our Zambrów. In

that time we made strenuous efforts but I am not exaggerating when

I say that were it not for the editor, Mr. Levinsky, the book would

not have appeared. His phenomenal memory made it possible to dig up

from the past, and from forgotten memories men and facts, incidents,

ways of life, histories of families and other interesting things

that ran their course in Zambrów years ago. He searched, rummaging

relentlessly day and night and uncovered sources relating to the

history of the town, especially in the Hebrew newspapers of the

times. He looked after giving a voice to the landslayt in

Israel and the world at large, especially those not inclined to take

pen in hand, encouraging and directing many in their writing. And

now, when the book lays before my eyes, a book of some seven hundred

pages beautiful Zambrów passes before my eyes like a panorama: The

streets and byways of the town, the Pasek6

and the marketplace, its synagogue and houses of study, its clergy,

the rabbis, dayanim7

and shamashim,8

and community political organizations; their leaders and hordes of

members; HeHalutz; prominent families who were so extensively

branched out; porters, wagon drivers, storekeepers and bakers, the

erudite bookseller Abba Rakowsky and other prominent townsfolk, the

young schoolchildren and the elderly hundreds of pictures that

preserve every aspect of the town of those days up to the Holocaust.

Many pictures that were donated were obtained only with great

difficulty in Israel and the United States. It seems to me that the

whole town, as it [once] existed, appears in this book. Not a one

has been overlooked.

The special chapter about the

destruction of Zambrów during the Holocaust is written by Yitzhak

Golombek, one of the living eyewitnesses and a survivor of

Auschwitz, and with him Yitzhak Golda and others. Read it with an

ache in your heart, but with respect and recognition for our heroic

martyrs, parents, brothers and sisters from the beginning of the

predation, the concentration in the ghetto to the extermination

you hear the reverberation of the cries of those who were taken to

slaughter, and you breathe in their final minutes.

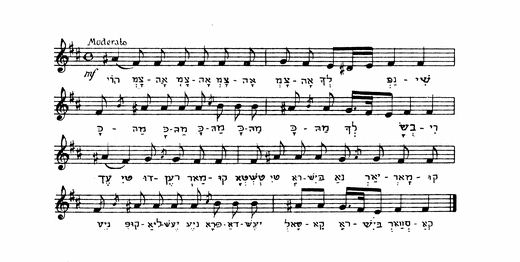

The folklore pages of the book have

special meaning. The editor has incorporated words and expressions

from Zambrów, which in part we still use to this day in our daily

affairs. Special chapters are dedicated to education, political

movements and social assistance. In addition there are descriptions

of various type of Zambrów folks, writings about the way of life,

etc. Using this, he truly takes us into the old home (alte haym)...

he deals here with the young people in the synagogue, societies,

work and industry, mutual aid, etc. The Zambrów societies of all

countries are described, their activities on behalf of the local

countrymen (landslayt), and for their brethren in all corners

of the world. I will not be exaggerating when I say that our

Yizkor Book will be one of the best of those that have already

appeared up till now, and we may take pride in it.

Our old home, Zambrów, is no more.

The sacred bones and remains of our townsfolk have not been given a

proper Jewish burial. Their remains lie in the great mass graves in

the forests of Szumowo and [Rutki]-Kosaki, and in the ash heaps at

Oświęcim. In the town only Christian peasants go about, who have

seized Jewish assets, and no one remains to take it back from their

hands. Only a few faded headstones remain in the cemetery among the

overgrowth and thorns, which indicate that at one time there was

Jewish life and a sizeable Jewish city.

This book is, and will remain for

generations to come, the truest memorial of Jewish Zambrów. In it we

have preserved the memory of the lives and the echo of the suffering

of the Jews who no longer exist. It is here that we have put a place

and a name9

to their light and their memory.

We therefore wish to thank our brother

organizations in the United States, with our comrade Joseph Savetsky

at its head, and in Argentina, and so forth for their material

help and great interest in the book. We thank those who took part in

the book by sharing their memories. We thank all of our landslayt

in Israel and outside the Land, and especially our friend Zvi ben

Joseph in Israel, who gave so much of his energy and attention to

the book. All of those who participated encountered difficulties

with all of the obstacles that laid in our way, and despite this we

produced a book that is both pleasing and substantive. At a suitable

time, let our townsfolk consult it, and let us leave thereby a

legacy to those children who will follow us, about the eternal way

of life of our people who lived it in our town of Zambrów הי"ד.

All, all of you, consider yourselves

saluted and blessed.

In the name of the Zembrover Landslayt-Organization in Israel

Zvi Zamir (Slowik), Chairman

|

The Historical Pages |

| |

|

By Dr. Yom-Tov Levinsky |

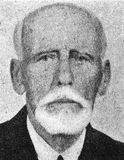

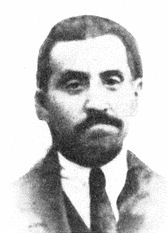

Dr. Yom-Tov Levinsky

|

|

A. When Did Zambrów Become a City?

|

A city does not simply spring into

being all at once. First, a small settlement appears, then a

village, and later when the village spreads out it becomes a town.

This certainly must have been the case with Zambrów. It was a small

village for many years, and after that a village. It was first, only

in the second half of the fifteenth century, that it grew large and

the residents demanded from the authorities the Mazovian

Principality that they grant it the status of a city. Their request

was accepted, after it was certified that Zombrowo satisfied all the

criteria to be considered a city.

In the year 1479, 5239 after creation, the ruler of Mazovia, who

ruled over the Płock Region, the Prince, Janusz II, was persuaded to

grant the Zambrów settlement the right to call itself a city

(Zombrow/Zomrow), and from that time on to enjoy all the privileges

of a city. Several years later, the residents of the city again

petitioned, on the basis that they did not have any regularly

scheduled fairs and the merchants of the surrounding towns avoided

coming to Zambrów, and therefore compelled the residents to travel

to buy goods at the market fairs of neighboring cities. Then, Prince

Janusz II officially designated this privilege upon Zambrów, even

nominating it to be a powiat (a central city). At this time, it was

already being called Zombrowo (Zambrówa)..

|

B. The Privileges of the City

|

The ruler granted the right to the city

to conduct two fairs a year. One on June 24 (Czerwiec), on the day

of St. John (Swiaty Jan) and the second on September 21

(Wrzesien), meaning: one fair before the harvest, and the second

after the harvest. The populace needed to wait three-quarters of a

year until the new fair. First, forty-four years later, when the

city had developed further and a number of villages became

affiliated with it, in the year 1523, the government of the Kingdom

of Poland, to which Mazovia de facto already belonged at that time,

decided to designate four additional fairs for the year a total of

six fairs. This was a symptom of a progressing city. With ceremony,

it was, once again, designated as a powiat. In 1527, when

Mazovia officially became part of Poland, the privileges of Zombrowo

were again certified.

In the year 1538, Zambrów was destroyed

by fire and sword. The war between Poland and Prussia, by

happenstance, took place in Zombrowo. The Prussian military

fortified itself in this place, afterwards called Pruszki. The Poles

were on the other side. The city, which was in the middle, was

meanwhile burned down and the residents all fled. In the year 1575

Zambrów belonged to Ciechanow, where the castle of the ruling noble

was located.

The new Polish King, Zygmunt I, son of

Casimir IV, heartily received a delegation of balebatim from

Zambrów, listened to their complaints, and took a hand in their

plight, promising to alleviate it. There were no Jews among them. He

lowered the taxes of the city, annulled all of their debts, and

renewed the privileges of the city, that had been lost when the

original copy of their official charter was burned. The members of

the delegation certified the details of the burned declarations by

oath.

|

C. The First Sign of Jews |

Were there Jews already [present] in

Zombrowo? It was not made clear to us whether there was already an

established Jewish community in the city, but what is known to us

[is that] the city government turned to the King, Zygmunt I,

10 to have him allow the movement of the market day

from Wednesday to Thursday, so that the Jews would be able to

purchase their requirements for Shabbat, the Jews being present in

the area in not insignificant numbers. However, a number of

incidents took place in the city that caused its decline. It is

possible to see this from the revenues [sic: of the market days]

that in the year 1620 the revenues from meat, honey, liquor and

grains were close to five hundred and eight florins (approximately

like gulden), and those [same revenues] in the year 1673 had fallen

to an income of thirty-five gulden. The area of the city and its

environs reached fifty-two voloki (the volok was twenty marg11),

and only nine of them constituted land that was being worked, with

forty-nine voloki remaining fallow.

We have already documented the fact

that the name was first written as Zambrów 'o, and later as

Zombrow.12

Stanislaw August II who ruled from 1764-1795, called it Zembrow

(according to Starozhitnya Polska 530-523). In the nineteenth

century, it was already being called Zembrow, and in Russian,

Zambrów. The Jews always called it Zembrow (according to

Pinkas Tykocin13),

and in the last century Zembrowo. In the list of the Jewish

census in Warsaw, from the year 1781, there are listed, among others

Jews that lived in Warsaw, but that came from Zembrowo. One

individual registered himself as follows: I come from Zembrowo,

and another, from Zambrów...

The name Zamrow-Zambrów appears to be

derived from the small river, Zambrzyce which is beside the town, or

perhaps the other way around does the river take its name from the

town? One is led to believe that in the thirteenth or fourteenth

century, there was a Prussian colony of the Teutonic Knights (who

were crusaders). Here, a summer vacation spot was located for the

German rulers, because the location was encircled by forests. It was

called the Sommerhof which [it is believed] that the Poles later

modified to Zomrow and according to the linguistic rules, either a

b' or a p gets inserted between the m and the r, for example,

Klumar Klumfurst, Kammer Chamber, Numer Number, etc. [In this

way] Sommerhof became Zombrow Zambrów.

|

E. The Political Situation |

Zambrów is administratively divided

into two parts: the city proper (called the

osada in Polish) and the gmina (the greater vicinity,

or community). The city itself was small, encompassing one market

square (Rynek), from which small streets emanated in all

directions. The horse market bounded the town on the west, and the

Poświątne on the east.

The gmina, however, had under

its jurisdiction, twenty villages and hamlets. By 1880, the gmina

had forty-four villages under its jurisdiction and numbered 12,154

souls. Jews also lived in those villages, some as tenant farmers (pokczary,

but the majority, up to about ten or more, were: Gardlin (Galyn, the

Bialystoker Road, where Shlomleh Blumrosens brick works was

located), Grabowka, Gorki, Grzymaly, Długobórz, Wadolki, Wiśniewo,

Wola [Zambrówska], Wiebrzbowo, Tabedz, Cieciorki, Laskowiec, Nagórki

[-Jablon], Sędziwuje, Poryte [-Jablon], Pruszki, Konopki, Koretki,

Klimasze, etc.

Zambrów belongs to Mazovia, an

independent but poor land that is rich in water, arable land,

forests, cattle and fish but is little-developed and stands at a

low cultural level. After the Crusades in Germany, from the year

1096 onwards, the local Jews began to immigrate to Poland. In the

twelfth century thousands streamed here thousands of German

Jews. Thousands also took up residence in Mazovia, [and] in the

older cities such as Płock, Czersk, Sochaczew, Wyszogrod, Płońsk,

Ciechanow.

With their full ardor, the Jews began

to occupy Mazovia and industrialize it. The lived here in

tranquility and were not subject to predation. Only when Mazovia

first began to draw close to Poland [proper] did limitations begin

to be imposed on Jewish citizenship rights. Nevertheless, Jews

enjoyed the privileges through a special law for Jews, Jus

Judaicum (Privilegium Judaeorum). The Jews integrated themselves

well into the local life and the Mazovian laws, even calling it our

law (Jus Nostrum). In the year 1526, Mazovia was integrated into

Poland, and they became one country. The Mazovian Jews now fall

under the laws and limitations that apply to Polish Jews.

|

F. Geography and Topography |

From time immemorial, Zambrów belonged

to the Łomża Guberniya (province) and is counted as its

second largest city according to its population. At the end of the

fifteenth century Zambrów was officially a powiat

(center). In the year 1721, the Polish Sejm divided the Łomża

Guberniya into two municipal districts: Zambrów and Kolno.

The chief city elder (starosta), resided in Zambrów.

Zambrów lies within the Cieciorki and

Wandolki forests, among others, not far from the famous forest area

of Czerwony Bór (about thirteen versts from Zambrów). And between

the cities: On the east is Czyżew, which has an important train

station to Warsaw and Bialystok; Wysoka and Jablonka to the west;

the train station Czerwony Bór and Łomża,

the provincial capitol of

north Bialystok and south Ostrów Mazowiecka.

Three small rivers ring the town: A.

The Jablon whose headwaters are in the town of Jablonka, courses

through Zambrów, flowing for a distance of about twenty versts to

Gać. B. The Prątnik, which emanates from the town of Prątnik near

Sędziwuje, and C. The Zamrzyce, which emanates from Wiebrzbowo and

flows into the Jablon. Jablon (or Jablonka) is the principal river

of the area.

Following a regulation promulgated by

the Zambrów community at the behest of the Rabbi, all of the little

rivers were officially referred to as the Jablon, in order to

facilitate the preparation of ritual divorce documents (e.g. a

get) in Zambrów: this is because the town river has to be

documented in the get. The provincial leadership accepted

this proposal.

About one verst from the town to the

east, the Uczastek of the military region is located. There were

[more than a few] Jews who lived here, who made a living from the

military. They had their own Bet HaMedrash

there, two bridges one made of wood and was [located] on the

ulica14

Ostrowska; and a concrete one on the ulica Czyżewska, which

connected the town to the surrounding settlements.

The Jews built out the market square (Rynek),

and one after another they erected houses around the marketplace,

opening stores, and in this way worked over the center of the town

and took commerce and industry into their hands. The gentiles

concentrated themselves around the horse market and the Poświątne

and engaged in agriculture.

Zambrów had good drinking water from

its streams. The principal stream was behind the Red Bet

HaMedrash, which provided for more than half of the town. A

second stream was on the

Rynek itself, and the water was obtained by a pump.

Water-carriers would also draw water from the river.

There were two (Jewish-operated)

steam-driven mills -- one was a water-mill, and four to five Jewish

manufacturing facilities. On the ulica

Ostrowska, near the water, there was a large Jewish dye plant. On

the other side of the city a large Jewish brick works (Gardlin).

Jews participated in small industry/business: they distilled

whiskey, made wine, brewed beer and made kvass and soda-water.

According to the census of 1578, there were six distilleries and

eight shoemakers, which also employed workers, five butchers and

eight bakeries. Having about itself the rich Jalowcowa forests, much

beer was brewed, which was given the name Jawlocowca Beer. In the

referenced year, in accordance with the tax rolls, it was

established that two hundred and forty-one barrels of beer were

brewed in Zambrów.

The city was consistently ruined by

fires, plagues, peasant uprisings, invasions by the Tatars, Swedes

and Prussians, such that, in the year 5560 (1800) it only had

eighty-one houses in it and a population of five hundred and

sixty-four residents. Part of the population lived in barracks, and

they cooked and baked under the open sky. In the year 1827, there

were ninety-one houses already (ten new houses in twenty-seven

years!) And the population numbered eight hundred and eighty-six15

people. And it was at this time that the Jewish initiative and

spirit of commitment to develop the city got started. In the passage

of four to five years the entire Rynek was built up, with

thirty new houses of Jews. In each house there was one or two

stores. The city established a cemetery, retained a rabbi, built a

synagogue, two houses of study, a bathhouse with a mikvah,

established a building for a religious court, founded a yeshiva

and Zambrów was a Jewish city.

In the year 1868, there are 1,397 Jews

in Zambrów, approximately sixty percent of the general population.

In the year 1894 there were already 1,652 Jews in Zambrów. In the

year 1895, at the time of the First Great Fire according to the

newspapers more than four hundred Jewish homes were consumed,

among them about a hundred Jewish stores and eating places, and

about two thousand Jewish residents were left without a roof over

their heads. The numbers speak for themselves.

The Jews of Zambrów had an interest in

making the city attractive to Christian worshipers, the lesser

nobility (szliachta), peasants and dyers, who, in going to

church, would along the way buy all their necessities. So, outside

the city, there stood a half-built church dating back to 1283. It

became ruined and had been burned several times. At the end of the

eighteenth century, the Canon of Płock, Martin Krajewski, became the

senior cleric of the Zambrów parish, and in memory of his parents he

reconstructed a wooden church, with a bell and a mortuary. The

Christians in the villages would go to worship in Szumowo, Jablonka,

Sędziwuje, etc., so that in Zambrów, a larger central church could

be built, which could accommodate hundreds of worshipers every

Sunday. The old church stood at the west of the city, beside the

horse market, to serve the worshipers there. The new church stood to

the east and attracted scores of peasants from all of the villages,

filling it on Sunday, along with the city streets and stores.

Two years after the fire the number of

Jews rose substantially, as seen in the census of 1897, where in the

Zambrów gmina (including the surrounding villages), there

were 10,902 residents, among them 3,463 Jews, nearly thirty-two of

the general population.

|

H. From When On, Were There

Jews in Zambrów? |

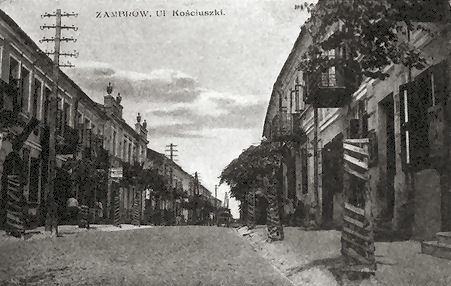

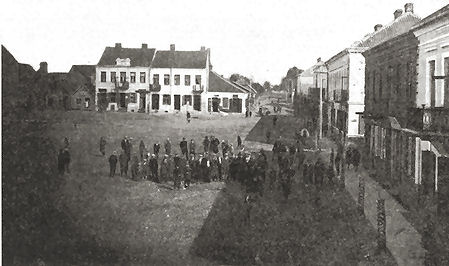

The Market Place (Zambrów Rynek)

It is difficult to answer this

question. Jews were already in Mazovia, the part of Poland where

Zambrów is located, since the beginning of the fourteenth century.

However, impoverished Mazovia did not have much attractive power,

and consequently few Jews settled here. Apart from this, the

political situation was not conducive; there were continuous

invasions by the Prussians and others that destroyed the land. It

was first at the beginning of the fifteenth century that the

circumstances began to improve, with the Lithuanian princes16

Janusz I in Warsaw and Ziemowit IV in Płock, who strove for peace

under the aegis of Poland. Consequently, economic conditions also

improved. Fields and woods bloomed anew, fish and wildlife, leather

and hides, flax and wool, honey and oil, all developed, and the Jews

found an attractive location here. Cities were established here, and

therefore for the first time, in the year 1471, we hear about Jews

in Łomża for the first time; the diocese of Płock spread its

ecumenical purview also to cover the Łomża district, and accused the

Scholastic, Stanislaw Modzielow of Łomża, in an assault on Jewish

merchants of Łomża and has him arrested.

|

I. Tykocin Protects the

Zambrów Jews |

Since the year 1549, the Jews of

Mazovia paid their national head taxes through the Vaad Arba

Aratzot, the Jewish Sejm, which was required to present the

kingdom with a specific sum of taxes on an annual basis, which was

collected in accordance with a set formula from all cities and

towns. Zambrów does not appear in this list, because a Jewish

community did not exist there yet. Tykocin, which was one of the

three central cities of Podlisze and collected the Jewish head tax

from the residents of Łomża, Grodno and other centers, imposed a

levy on the surrounding small settlements where there was no

community, and strictly demanded taxes and regulated issues between

Jews and gentiles, and took care to assure that one party would not

unjustly take away the livelihood of the other, in land leasing and

in liquor distilling, fields and gardens, milk and cattle, mills and

the like. If there was a larger settlement then Tykocin would

impose the mission on the community or on the religious court of the

town, to the point that if a city in the area was mentioned in

referenced acts, for example, even one that was as large as

Bialystok, it was added to be in the vicinity' of Tykocin, because

Tykocin was the capitol city of the district up to 1764, until the

Polish regime dissolved the Jewish Sejm the

Vaad Arba Aratzot, which was a government within a government,

and adopted other and better means to collect more head taxes from

the Jewish populace. Also, afterwards, Tykocin continued to be the

chief city of the district. Regarding Tykocin, we know that in the

year 1676 (5436) the community adopted a resolution under penalty

of excommunication consisting of seven decrees, and extinguishing

black candles, with trumpets and blowing of the shofar: that

no one has the right to raise either hand or foot to deal in strong

drink, not as a business or for sustenance, whether by license under

the government, as a tenant, under beverage-making duty, or

beverage-selling duty, etc., without the cognizance and express

permission of the community. Everything must first be presented to

the community and its leadership, who must thoroughly and completely

examine it without the presence of the petitioner. Whatever they

decide is to be recorded in the Pinkas of the community (all

this according to the Pinkas of the Vaad Arba Aratzot,

p. 148, sign שנ"ב). The Pinkas of the Tykocin community no

longer exists, as was the fate of many of the

Pinkasim of other cities. However, during the First World

War, when the Jews of Tykocin were compelled to abandon their city

the

Pinkas was placed in the hands of the Rabbi of Bialystok,

Rabbi Chaim Hertz. His grandson, who is today a professor of Jewish

history at the University of Jerusalem, Dr. Israel Heilperin,

secretly made a copy of the protocols of the ancient Tykocin

Pinkas and in this way, managed to preserve them for posterity.

Among the protocols (which are still in manuscript form) we find the

name of Zambrów mentioned in isolated places, and we have made note

of them.

|

J. The Jews of Zambrów in the

Year 1716 |

ulica Kościuszki

(Koshare Road)

We now turn back to Zambrów, as it was

in those times. There is a theory that in this location there

already was a small Jewish settlement in the sixteenth century, but

that it was disbanded in response to the residents, who had the had

the discretion not to tolerate having Jews in their city (de non

tolerandis Juudaeis), as was also the case in Łomża and other tens

of cities and towns in Poland. We do not possess any documents with

which this can be established. Zambrów was also not an important

point and did not have any substantial undertakings that would merit

mention in government regulations.

We are able to extract from the Tykocin

Pinkas that in the year 5476 (1716) there still was no Jewish

community, despite the fact that Jews lived here and ran substantial

businesses. On page 164, volume 748 of the Pinkas, it says:

income-producing business and the house where R Shmerl ben Yitzhak

lived, passed into the hands of the brothers Yehuda and Shmuel, the

son of the previously mentioned Shmerl, and they are entitled to

right of enjoying its benefits in perpetuity. This remains the case

even if there is a change in city Elder, or the Elders death, or if

a gentile will have possession of the business for a number of

years, and if someone wants to repurchase the business from gentile

hands he has no right to do so, because it belongs only to

Shmerls children. This was approximately in the year 1716.

On page 271,volume 796 of the year 5476

(1716) it is again told that Yitzhak son of R Yaakov of Jablonka

bought the franchise (the right of Furmanka use of a wagon) to

collect franchise taxes from the Zembrowski Powiat in the

Łomża Guberniya. All the franchise promissory notes from the

previously mentioned powiat, are his prerogative in

perpetuity, even in the event that he should no longer reside in the

powiat.

|

K. Zambrów Has No Control over

Cieciorki |

In the same

Pinkas, page 797, of the year 5476 (1716) there is a

reference to a sharp discussion that took place between Tykocin

and the Jews of Zambrów, with regard to the control of the liquor

franchises in Cieciorka. The noble of that region had constructed a

distillery on his estate and leased it to the Jews. As was the

custom, a Jew could not independently come to lease such a facility

only with the facilitation of the Tykocin community could that be

accomplished. And here, the community permitted the lease to go to

one, R Jekuthiel. The Jews of Zambrów argued that they had a prior

right to the lease, based on proximity.

In the same year, and on the same page,

it is recorded that the lease to the distillery of Cieciorki, which

is near Zambrów, was sold by the dozors of the community to

Mr. Jekuthiel son of R Mordechai, and 'no Jew may approach there

(to infringe on his territory) because it belongs to him, in

perpetuity' after it was certified that Cieciorki is further from

the boundary of Zambrów, and that is why it was sold in perpetuity

to R Jekuthiel. This means: the Zambrów community has no say in

whether the distillery is leased to a Jew from Zambrów, or a Jew

from Jablonka, because Cieciorki is far from the Zambrów border and

therefore does not belong to it.

|

L. To Whom Does Sędziwuje

Belong? |

It appears that the previously

mentioned R Shmerl was a businessman on a large scale and had

leases on businesses, not only in the city of Zambrów, but also in

the gmina, meaning the larger district encompassing Zambrów

and its surrounding villages (Wola Zambrówska), Nagórki, Klimasze,

which according to all our information were attached to Zambrów, and

whoever had a franchise for a certain way to make a living in

Zambrów that privilege extended to the villages. Sędziwuje was

exempted because allegations were made that it was far from the

Zambrów city limits, and is therefore not included, and as a result

a local resident has the right to take the franchise for this

village.

In protocol number 784 of the same

Tykocin Pinkas, we read: The decision of the chief rabbi,

Rabbi Yehuda, son of the [former] chief rabbi Shmeri Zembrover,

that all the villages in the ambit of the city of Zambrów are under

his jurisdiction, and no man has the right to infringe upon that

right, as if it were in the city of Zambrów itself and within its

borders. And these are the villages whose status was clarified as

being within this ambit: Sędziwuje, Wola, Nagórki, Klimasze.

However, a protest went out regarding Sędziwuje, which is further

from the borders [of Zambrów], and an outcry was made to settle the

matter by measurement by someone trusted by us, and for as long as

the matter is not clarified the village will remain under the

jurisdiction of the [Zambrów] community.

Tuesday, 14

Iyyar 5476 (1716)

This means: The previously mentioned

Yehuda son of R Shmerl, one of the two brothers who inherited the

franchise for the spirits business in the city of Zambrów from their

father, and no one is permitted to infringe on their franchise in

the city registered a complaint in the religious court in Tykocin,

that other Jews were grabbing pieces of his income, and violate his

right. because they have income from the nobles, part of whose

assets is from Zambrów. The defendants defended themselves with the

excuse that they transact business only in those villages that are

not under the control of Zambrów. A special session was called to

clarify this matter. All the previously mentioned villages were

measured, to determine if they were close to Zambrów, from the

border to the city. They discovered that the villages of Sędziwuje,

Wola, Nagórki and Klimasze were close to Zambrów, and therefore are

included in its ambit. For this reason, no one may infringe on the

franchise of R Yehuda son of R Shmerl. The protest of the accused

is just, in that Sędziwuje is more distant from the Zambrów border.

However, their complaint was not yet researched enough, and calls

to attain the truth by means of measurement. Because of this,

Sędziwuje was declared to be a free-city; it did not belong to

Zambrów, but was not considered out of Zambróws ambit. In the

interim, the Tykocin community will manage the village, and will

designate who may practice the businesses and estates of the nobles

of Sędziwuje. The judgment was carried out on 27 Iyyar of the

year 5476 (1716).

A short time after this, we read, in

volume 785 of the Tykocin Pinkas

(page 269) that the religious court determined that the village of

Sędziwuje is at a further distance from the border of the city of

Zambrów, but not more than one quarter of a verst. This became clear

through the testimony given by someone who had personally measured

the distance. The judgment was carried out on Monday, 2 Elul,

of the year 5476 (1716) and the protocol was signed by: Abraham

Auerbach, Yitzhak son of R Abraham, and Gedaliah son of Menachem

the Kohen.

The previously mentioned R Yehuda son

of R Shmerl appears not to have remained silent, and complained

that one quarter of a verst was hardly a distance that was

significant, and that he alone, had the right to [the business of]

Sędziwuje, and that right was his as a citizen of Zambrów, and did

not belong to anyone else. This matter dragged on from the month of

Elul 1716 [5476] to Iyyar 1717 [5477]. And finally, in

the end, a judgment was promulgated on the basis of research and

investigation, and credible witnesses that Sędziwuje is far from

Zambrów and does not belong to it, therefore it is under the aegis

of the Tykocin community, and that the owner of the Zambrów

franchise has no longer any basis for dispute and complaint against

the village, [written] Wednesday, 16 Iyyar 5477 (Lag

B'omer

eve, 1717). Signed by Yitzhak ben R MY.

We did not find anything else in the

Tykocin Pinkas about Zambrów. We can, however, infer with

great confidence that if there had been a community in Zambrów with

its own religious court building, that Tykocin would not have

involved itself in the issues of the city. Zambrów would have

independently defended its own interests, even if it would have had

to secure the concurrence of Tykocin.

|

M. The Founding of the Chevra Kadisha

in the Year 1741 |

The cemetery at Jablonka served Zambrów also, as well as other towns

in the area including the villages of Nagórki, Pruszki, etc. At the

beginning the bodies of the deceased were brought to Jablonka by

wagon, as they were. The Chevra Kadisha of that town then

dealt with the bodies subjecting them to ritual purification,

dressing them in burial shrouds and interring them. However, this

was not out of respect for the deceased having to leave them for a

period of time without undergoing purification, but this was the

custom in the smaller settlements. When the settlement at Zamborow

grew more populous, it was decided to establish a Chevra Kadisha

there, which was to deal with the deceased in that location, and to

bring [the body] already purified to Jablonka to its final resting

place. As is recorded in the Pinkas HaYashan [The Old

Folio] (according to the eye witness R Yehoshua Gorzelczany) the

Chevra was established on 17 Kislev 5501 [Tuesday,

November 25, 1740].17

It seems that the founding was accompanied by a festive banquet,

because the above date is the day of the Chevra

banquet in several [sic: neighboring] communities. Because the

simple goal of the Chevra, the dirty work, was the digging

of the grave and performing the burial that was done by the men of

Jablonka. The men of the Zamborow Chevra permitted them to

add a condition in the Pinkas: whoever is not knowledgeable

in the study of a chapter of the Mishna, cannot be a member

of the Chevra Kadisha.18

In a similar fashion, the honorific Morenu [Our Teacher]

that is added to one called for a Torah aliyah, was given to

a man only by the Chevra. The heads of the Chevra were

learned men, and it was possible to establish who was a scholar and

rightly could be called: Let Our Teacher R So-and-So the son of

So-and-So..., and from whom to take away the title of Morenu

if it was improperly bestowed. From this point in the Pinkas,

it is possible to easily infer that these were learned Jews. The

Chevra Kadisha was a catalyst to the formalization of a

community, with all of the requisite appointments, and that did not

tarry in coming.

|

N. By 1767 There Still Is No [Jewish] Community |

On March 21, 1767 (20 Adar 5527)

the government commission of the royal treasury (Kommisja

Rzeczypospolitej Skarbu Koronnego) designated those communities that

now belong to the Tykocin region, with regard to the level of taxes

and the collection from both. Nineteen towns are enumerated there:

Augustow (Yagustowa), Bocki, Bialystok, Goworowo and its

surroundings, Goniądz, Wizna and its surroundings, Zawady and its

surroundings, Jesionowka, Jedwabne, Loszyc, Niemirow, Sokoly,

Sarnak, Konstantynow, Rutki and its surroundings, Rostki and its

surroundings, and Rajgrod.

Zambrów, which is not far from

Jablonka, and Rutki are not in the list! And yet, we know from the

dispute between Yehuda son of R Shmerl and other lessees, in

connection with the rights over the Zambrów [liquor] franchise,

Tykocin got involved and decided who was right. [We deduce that]

Zambrów was, indeed, under Tykocin tax control. This means: Jews

were living here, but not organized into any sort of a community,

without a rabbi, without a mikvah, and without a cemetery.

It is only first, at the beginning of

the eighteenth century, that the history of the [Jewish] community

in Zambrów begins. The original settlement was in the villages of

Pruszki and Nagórki. The distance between these two villages was not

great, and it was there that a Bet HaMedrash

was built, which also served as a cheder for the children.

Older children were sent for education to the surrounding towns:

Jablonka and Śniadowo. Śniadowo has a reputation as a large Jewish

community, and its rabbi even had aegis over Łomża, which at that

time still did not have its own rabbi, and not even a bathhouse.

(According to Polish municipal regulation, it was necessary to have

a special concession for a bathhouse). The Jews of Łomża, from one

side, and the Jews of Zambrów from the other, would travel or walk

on Friday, so... as to go to Śniadowo to bathe, and wash themselves,

get their hair cut, and sometimes be cupped or have blood let all

in honor of the Sabbath.

|

O. The First Cemetery In the

Year 1828 |

ulica Wodna (Wodna Street)

The number of Jews who took up

residence in Zambrów proper grew larger and larger. They observed

that it did not make sense to leave Zambrów to go pray at the Bet

HaMedrash in Pruszki, so they formed their own prayer quorum in

Zambrów and two Torah scrolls were brought in from Tykocin, borrowed

for a short period of time. The Jews of Zambrów set about having

Torah scrolls written for themselves. The settlement in Pruszki

supported its existence and remained connected with the Zambrów

Jews, as if they were one town. An incident occurred where a Jew in

Zambrów died, and it was necessary to have him taken for burial to

Jablonka, by way of ulica Sędziwuje. The weather was bad

with heavy rain, and the road was covered in mud, rivulets of water

and potholes, because no paved road existed there yet at that time.

Therefore, it was necessary to defer the funeral to the following

day, and to the day after, and this was considered to be a great

offense to the deceased. So on Saturday night the Jews of Zambrów

and Pruszki came together in an assembly and decided to create their

own cemetery, on the way that was, indeed, between Zambrów and

Pruszki. R Leibeleh Khoyner, the ancestor of the Golombeks, then

donated a parcel of land, and with ceremony, it was decided to step

up to the preparations: obtaining permission from the authorities

and indeed, also the concurrence of the Chevra Kadisha in

Jablonka, which each year demanded a certain stipend from the

Zambrów Jews towards the upkeep of their cemetery and the expenses

of the Chevra [Kadisha]. A liberal wind was blowing

through Poland at the time under Russian rule. This was evident in

the relationship of the Poles to the Jews in Łomża, the provincial

capitol, from which the permission was supposed to come. When the

permission arrived, they began to cordon off the field and build a

small structure for purification of the deceased bodies. In the year

1828 (5588) the first cemetery was dedicated.

The community in Łomża was established

anew in the year 1812, under the influence of the spirit of

Napoleon, who created the slogan among the Poles with regard to the

Jews: Kochajmy się, meaning, Let us love one another! In 1815

Poland came under Russian rule. The Russian authorities wanting to

disrupt the unity among the Polish population, removed many of the

Polish limitations placed on Jews. Despite this, the Polish

Kingdom under the Russians resisted this, and in the effort of a

delegation sent before the regime in Warsaw, in the year 1822, they

succeeded to create anew, a ghetto for the Jews and limit their

rights in Łomża. This was also the case in Ostrołęka and other

places. It was first, in the years 1827 and 1828, that Poland

secretly began to prepare for its first uprising (powstanie)

against Russian rule (1831). It was necessary to co-opt the Jews,

and because of this, liberal winds began to blow in Poland. It was

therefore not difficult to establish a Jewish community council in

Zambrów. The Jews of Zambrów, at that time, actually favored Poland,

and were patriots on its behalf, even in the uprising of 1863.

The

Chevra Kadisha grew and reorganized itself. A Pinkas was

initiated. The first gabbai was the father of R

Chaim-Pinchas Sheinker. Later gabbaim were: Monusz Golombek,

Shmueleh Wilimowsky, Binyomleh Golombek, Abraham Moshe Blumrosen,

Abraham-Yossl Wilimowsky, and Yankl Zuckerowicz. Zuckerowicz was the

last gabbai. The Nazis drove him to Germany and tortured him.

When he returned exhausted, at the end of 1939, under the rule of

Russians, he collapsed and died.

Of the martyrs, the names of the

following are recalled: Abraham-Moshe and Wolf-Hirsch Kuczapa, his

son, Elyeh, Israel-David Zibelman, Motl Melsheinker, and Yitzhak

the Dyer.

Approximately in the year 1890, the

cemetery was filled to capacity. The community then purchased a new

location for a new cemetery, which bordered on the old cemetery and

appeared like an extension to it. It has been said that a question

arose among the gabbaim at that time, about what is to be

done with the ohel (the small building for purification of

the dead): should the old one remain in place, which will now be at

the [extreme] end of the new cemetery, and the deceased will have to

be carried through the cemetery to be purified over all of the

graves that will in time appear or build a new ohel, at

the entrance of the new cemetery. R Shmueleh Wilimowsky said that

the ohel should remain in its old location, and all that is

needed is to rebuild it and enlarge it. Monusz Golombek argued that

it makes better sense to have it at the entrance, so that it will

not be needed to carry the deceased for a long distance, if it

should be on a rainy day or during a snowstorm. To this end, he

proposed with humor: we are not going to live here forever. In a

hundred years, we are going to be buried somewhere here, in a

respectful place, at the front as gabbaim, and in the

coming generation when the cemetery will be full of graves, and the

members of the Chevra Kadisha will exhaust themselves by

carrying the deceased for such a long distance they will point to

other graves on their way through, saying: Here lie the elder sages

of the community, who lacked the common sense to build the ohel

at the entrance, and put it so far away... [at that time] will it be

pleasant for us to hear such talk? When no good will be said about

us at the entrance, at least we will not be in a position to hear

this embarrassment... At this, Shmueleh Wilimowsky laughed heartily,

and agreed to what R Monusz proposed.

In the government regulation about

having their own cemetery, they already had incorporated the right

to create a Jewish community in Zambrów. And this did not take

very long. The communal statute was declared in the same year.

|

P. The Synagogue and Houses of

Study |

|

The Synagogue

|

|

The Entrance of the Synagogue

|

At first, prayer was conducted in small quorums. In general, the

town consisted of small, wooden buildings, with straw roofs, and

without making any comparison, even the church was made of wood,

just outside the town, not far from the horse market.

One of the wealthy balebatim, R

Leibeh, the son-in-law of Elyeh Katzin, built the first building on

the marketplace and opened a very large tavern there. He was

schooled in Kabbalah, and a very decent Jewish man. R Leibeh

died suddenly while still young. His young widow, Rosa the Tavern

Keeper or Rosa of the Building gave over part of her house to be

used as a Bet HaMedrash, and this was the first house of

study in the town.

They were not, however, content with

this: the town needed a synagogue. Accordingly, a collective action

was taken. Balebatim bought places even before the

synagogue was built, and up front they paid a larger amount of money

for the good of the building. R Monusz Golombek donated the

parcel that stretched past his yard in the direction of ulica

Łomżyńska, for the synagogue. The provincial engineer permitted a

street to be cut between his house and the synagogue.

The synagogue was constructed of stone

and mortar, made of strong bricks and stone walls. At the beginning

of the construction, the history of the synagogue building was

written down on parchment, who donated the parcel, and who made

contributions to the building fund, and it was sealed well in an

earthenware po and embedded in the foundation19.

When the foundation was torn apart in later years, at the time the

new synagogue was built, it was found it was reread, and once

again imbedded in the foundation.

After the construction of the barracks,

when the town had grown by several hundred new worshipers and the

synagogue became crowded it was decided to build a large Bet

HaMedrash. A dispute arose in the shtetl: The grumblers

complained: it is necessary to build a stone Bet HaMedrash,

on the other side of town, on the way to Cieciorki, so that it would

be nearby for those that lived far off. The Golombeks argued: we

dont have to be pretentious, and if the synagogue is made of stone

the Bet HaMedrash should be made of wood, since this is the

way things are done by Jews.

Until the time Monusz Golombek turned

over his parcel, which bordered on the synagogue, and wood was

procured, and boards were carpentered, and the wooden study house

started to go up slowly, beside the synagogue... at which time

Shlomleh Blumrosen and his partners donated ten thousand bricks from

his brick works, Herszak Bursztein donated a place, and a stone

Bet HaMedrash was erected. It was at that time that they began

to call [them] the Wooden Bet HaMedrash and the Stone

Bet HaMedrash, or the New

Bet HaMedrash. During the time of the First Great Fire of 1895,

the wooden Bet HaMedrash was consumed along with the

synagogue. The stone Bet HaMedrash remained intact. In place

of the wooden synagogue, a stone synagogue was erected already in

about three years time, made of red brick, in accordance with the

initiative of the forthcoming Golombeks Leibl and Binyomleh. It

was therefore called the Red Bet HaMedrash, and the New-Old

Bet HaMedrash, which was colored white, was called the White

Bet HaMedrash, until the town was destroyed. The synagogue

remained in burned ruins for nearly thirteen years. At first, when

the Red

Bet HaMedrash was not yet available, they would worship in

the burned out synagogue, between the walls, covered with a sort of

tarpaulin.

Rosas building, where the first Bet

HaMedrash in Zambrów was housed, went into the hands of R

Hirsch Michal Cohen. When the synagogue was built, the Bet

HaMedrash was liquidated. This then became the location for R

Chaim Nahums dry goods store. The house was rented to the municipal

chancellery, and in place of the old Bet HaMedrash...the

municipal jail was put in place [die Kozeh]. The building was last

bought by Yisroeleh Shia-[Be]zalels.20

|

Q. The Bathhouse and the

Mikvah |

There is no city that does not have a

bathhouse and a mikvah. There had been a mikvah in

Zambrów for many long years. Without one, a Jewish settlement cannot

exist; however, a bathhouse requires special permission from the

authorities. It was difficult going with the bathhouse: the

authorities were not easily persuaded to permit a bathhouse to be

built that is to say, a place to bathe in honor of the Sabbath.

From the perspective of the authorities, it had not yet been

demonstrated that this was necessary for the populace... the Poles

actually did not bathe. Up to the nineteenth century, only special

towns had concessions for a bathhouse. It was the gabbai

Shmueleh Wilimowsky, who built the bathhouse in Zambrów. The Jewish

community invested about fifteen hundred rubles in the building. It

was built on community land near the Hekdesh. The bathhouse

had its own special brook, a cold and warm mikvah, a sauna to

steam oneself, and a cold room, after being switched with branches.

The bathhouse was leased for either a year or three years, and the

community had a significant income from it. It was lit and heated on

Thursdays for the womenfolk, and on Fridays for the menfolk.

Occasionally, the baths would be kindled in the middle of the week,

and it was shouted out in the streets: the bath is being heated!

Friday, at midday, when the bath was thought to be sufficiently

heated (only men used the steam room) the stones in the oven would

glow, and Józef the Shabbos-Goy had provided for enough

switching branches, and the shammes would go out into the

street intersections and announce: To the baths! The military

represented a large clientele for the baths. Soldiers, officers

would fill up the baths, sometimes causing a scandal.. accordingly,

for a while the bathing season was regulated: after candles were lit

the soldiers can come and a gentile keeps watch and collects the

entrance fees.

They did not always succeed in having a

good bathhouse manager. The last of these was R Alter Dworzec (Koltun),

and it appears that the whole history of the baths came to an end

with him.

Together, with the growth of the

[number of] Jews in the city, the Christian population also grew.

They began to settle in the northeast side of the outskirts of the

town. Here also is where the post office was set up, the court, and

the religious Catholic institutions. And this is the history of the

gentile section at the outskirts.

Behind the Rynek, on the way to

Czyżew there was a large stretch of government land, that was called

Poświątne. Shmueleh the Butcher bought this land from the

government for a song. Shmueleh the Butcher had an in with the

government and was the contractor who supplied meat to the military.

Accordingly, he got this parcel for a cheap price. A short time

afterwards, the Zambrów parish decided to build a large, stone Roman

Catholic church in place of the older wooden building that stood at

the entrance to the town, not far from the Jewish cemetery. Since

Shmueleh the Butcher sold off a parcel at a cheap price for the

construction of a church, Jews also bought parcels and built new

little houses along the church street, ulica Kościelna,

because this location had developed into a source of livelihood:

every Sunday, when the gentiles would gather from the surrounding

villages, to perform their religious rites, they provide a great

deal of earnings. The Jewish settlement grew and branched out

further in this manner.

In the year 1882, Zambrów became a

military [focal] point. The Russian authorities decided to garrison

two full infantry divisions and an artillery brigade there. Smaller

detachments of soldiers had been in Zambrów for a while, previously.

Immediately after the Polish uprising (powstanie) of 1863,

soldiers were stationed in Zambrów. Seeing as there were no barracks

yet, they were dispersed throughout the town. At the location where

later there was a place for receiving guests, and the old home of

the Rabbi, and his small court house was the post, and at the

place of the Red Bet HaMedrash a mustering place for the

soldiers. The Jewish populace suffered some bit of morale problems

because of the soldiers. They would constantly come around begging

for food, especially on the Sabbath a piece of fish and a piece of

challah. Jewish daughters would be fearful of answering the door

at night. Jewish children learned the profanities used by the

soldiers. On the other side, they brought in income to the town.

Jewish tailors and shoemakers, bakers and storekeepers who sold

clothing, made a good living, and the population of Jews in the town

increased. It was only after deciding to station two divisions of

soldiers, that consideration was given to constructing barracks. To

this end, Captain Radkiewicz was sent to Zambrów from the Warsaw

Military District. He then purchased a large parcel of land from

Shmueleh the Butcher, on the road to Czyżew, on which to erect the

military compound: tens of barracks, places for drilling and

mustering, a Russian Orthodox chapel, housing for the officers,

warehouses and stables, an arsenal for ammunition, clothing, etc.

The contract to put up the entire military compound was taken by a

Jew from Łomża, named Manes Becker. He was an orphaned and solitary

young boy who studied at the Talmud Torah in Łomża. Later on

he apprenticed with a mason and worked his way up a little at a

time, until he became a contractor for sizeable structures. Together

with his son-in-law Abramowicz (the son of the coppersmith of

Lochow), he built the first of the military barracks on ulica

Kościelna, and the street then took the name Koszaren21.

Many Jews, tradespeople, merchants, contractors, all made a good

living at the Koszaren. Those Jews who were engaged in the

construction, were called' koszarers: Avreml Koszarer, Herschel

Koszarer, etc.

Zambrów became a large Jewish town that

provided sustenance to hundreds of families, and people came to

engage in employment from all directions.

With the growth of the town in line

with the needs of the Jewish populace, which made meaningful use of

the post and telegraph services, the small post office on ulica

Wola near the nobleman Sokoliewski, moved over into the large

premises in Bollenders house on the Uchastek. The post office was

in Jewish hands and was closed on the Sabbath. Letters and other

posted articles were conveyed by Jewish wagon drivers to the train

station, and from the train station in accordance with an annual

agreement with the postal authorities. The first mailman was Jewish,

Alter the Mailman. His mother was a midwife and had relationships

with the wives of the nobility and the wives of appointed and

employed people. It was because of her connections that he became

the mailman. The post office served the entire Zambrów gmina.

However, it would not distribute to local addresses in the villages.

They would have to come to get their mail.

No small number of Poles fled the

country after the Polish uprising. Accordingly, their parents and

relatives would come every Sunday to Alter the Mailman, to inquire

whether or not a letter had arrived. Often he would set out a small

table on Sunday, not far from the church, and respond to the

interested parties. He was well compensated for letters with produce

from the villages and money. So Alter became rich. His two-story

wooden house on ulica Ostrowska was one of the nicest in the

town.

In time, the post office bought its own

horse and wagon and transported the postal items to the train, as

well as passengers. The post office could no longer remain closed on

the Sabbath because of the Jewish mailman.

The post office became secularized, and

the meaning of Jewish mail was again applied to letters that were

not delivered in a timely fashion, but languished somewhere in a

pocket. Alters position was taken over by a gentile from Goworowo.

As previously mentioned, Zambrów

survived a number of fires concurrently. However, of special note

was a Jewish fire that broke out in the month of Tammuz (July) of

1895, which burned down the entire Jewish settlement, the synagogue

and the Bet HaMedrash. From that time, Jewish Zambrów began

to reckon time with reference to this fire: [to wit]: I was born a

year after the fire. Such-and-such was before the fire, etc.

The first great Zambrów fire made

[quite] an impression and was written up in HaMelitz and

HaTzefira the two Hebrew daily newspapers of Russia-Poland. No

Yiddish newspaper existed yet.21

Mr. Benjamin Cogan writes in

HaTzefira, Friday, the Parsha of Balak, 5655 (1895), that

a large fire broke out. Approximately four hundred houses were

consumed, [as well as] one hundred stores, food shops and storage

facilities, two houses of study, and the synagogue. Only twenty

houses remained, and about two thousand people were left without a

roof over their heads. When the news reached Łomża, R Nachman

Drozowsky organized an aid initiative. The rabbi, R Malkhiel, went

from house to house with

balebatim on the Sabbath to collect food, clothing and money.

In

HaTzefira of 15 Av 5655 (1895) number 167, the committee

thanks Mr. Eliyahu Frumkin of Wysokie, on behalf of the victims of

the fire, for the bread and one hundred rubles that he came up with.

The committee approaches the public with a request for assistance to

the unfortunate of the town after the fire. When Czyżew, Sędziwuje,

and Rutki had burned down Zambrów did not rest, and it collected a

lot of money and clothing. Accordingly, it was now time to return

that help.

In

HaMelitz of November 19,1895 in 29/11. The rabbi, R Dov

Regensberg, thanks his friend the editor for the aid initiative that

he published in his newspaper, which on one occasion brought in one

hundred and fifty rubles and another time fifty rubles.

In

HaTzefira, number 55 of 3 Nissan 5556 (1896), the

correspondent complains that since the Kozioner Rabbiner22

R Moshe David Gold moved to Nowogród, municipal affairs have been

neglected. The Chevra Kadisha requires one thousand rubles a

year for its needs, and no fence has been put around the cemetery.

Today, one finds bones there...the money that was sent for those who

were burned out has been distributed without an accounting, and

those who stood closest to the trough were the first to benefit from

it...

In

HaTzefira Number 36, from the year 1897, Y. Gurfinkel writes

that the economic situation in the town has already improved, the

kosher canteen for the observant soldiers who do not wish to eat

non-kosher food from the [regular] canteen has reopened after two

years of dispute. Before this, a midday meal would cost a soldier

ten kopecks, and as a result there were few patrons. Now a midday

meal is much cheaper because the contributions from the supporters

have increased.

|

V. The Zambrów Gangsters |

Every town had its own pejorative

nickname. For example there were the Wise Men of Chelm, and Warsaw

Thieves. In the Zambrów area there were: the Gartl-Wearers of

Czyżew, the Bullies of Ostrów, the Kolno package [carriers], the

Jablonka Goats, the Guys from Łomża, the Jedwabne Crawlers, the

Cymbal Players from Staewka, etc. Every town knew how to describe

its pedigree and the story of its nickname.

Zambrów also had such a nickname: the

Zambrów Gangsters, meaning, bands of thieves. This name was

notorious in Poland. In a book, By Us Jews, which appeared in

Warsaw in the year 1923, Mr. Lehman tells in his article Thieves

and Robberies (page 56) why people from Zambrów are called

gangsters: In the sixty to seventy years (it really should be

seventy to eighty) of the previous century, there were gangs of

horse thieves in Zambrów. It has been told that the horses were

stolen from deep inside Russia, and at night they were brought to

Zambrów, and they were quartered in the stables of the large Zambrów

taverns. A couple of nights later the horses were taken out of their

clandestine stalls and taken off to the Prussian border. The

investigating judge, Tuminsky, undertook to excise these gangs, and

he succeeded. That is what is written there in the book.

Correspondence concerning the trial of

the gangsters was printed in the two Hebrew daily newspapers at the

end of the prior century [in] HaMelitz in Odessa, and

HaTzefira in Warsaw, and we will introduce them here, in

abbreviated form: A certain A. Z. Golomb wrote the following in

HaMelitz Number 123, on June 4, 1887: Approximately ninety men

joined together, from the entire area, even as far as Grodno, and

carried out large scale thievery and murders, assaults with intent

to rob, and so forth. However, they were especially notorious for

the stealing of horses. The Chief of the Secret Police in Łomża

harassed these thieves, so they stole his horse as well. When he

became very upset and ashamed, the thieves told him: he was to put

two hundred rubles in a certain place, and they will then return his

horse to him. He placed the money in that spot and they took the

two hundred rubles and didnt return the horse as well. At that

time, he did a very daring thing: he traveled to Petersburg, and

went through a course on how to apprehend thieves. Upon his return

to Łomża, he had acquired the [added] title of 'Court

Investigator and obtained all the rights to arrest the gangsters.

His attack against the gangs lasted for three years, until he

captured and arrested them all in Łomża. The trial took place in May

1887 in the Łomża district court. Among the accused and held in

irons were thirty-three Jews from Zambrów. The sentence was

announced on May 28: Of the men, twenty-three were found guilty, and

ten innocent. One of them, Moshe, was accused of informing on a

gentile. Joseph L. and Joseph Sh. robbed and raped a noblewoman. A

boy, Mikhl L,. stole a goose and a few days later attacked the owner

and beat him, because the goose was so scrawny. Among those arrested

were a number of prominent and respected balebatim from

Zambrów, owners of taverns, who were sentenced to several years of

imprisonment. Two prominent horse dealers from Zambrów, Y. and N.,

were sent to Siberia with their wives and children.

In the June 28, 1887 edition of

HaTzefira, Abcheh24

Rokowsky (see a separate chapter about him later on) offered a

rebuttal to the article by Mr. Golomb, indicating that he was guilty

of a sacrilege, because the Russian and Polish dailies seized on it

and reprinted it. Mr. Rokowsky argued that the court had added a

variety of criminals to the trial of the gangsters, because the

police, in this manner, wanted to raise its prestige. [He complained

that] prominent

balebatim from Zambrów were arrested, not because they were

partners in the gangs, but because they were considered disloyal

citizens: they had not told the authorities that the gangsters were

stopping off in Zambrów on their way to the Prussian border. Abba

Rokowsky writes that Mr. Golomb created a tempest in a teapot

[literally: a storm in a glass of water] and had insulted the

Zambrów Jews.

This matter was discussed for many

years in the shtetl. It was later shown that a political

issue was involved here: Germany was interested in buying Russian

dragoon horses. A gang of non-Jews, Poles, carried this out. They

would bribe soldiers who stood watch, officers, etc., and they

opened the military stables. Some of them would then mount some of

the horses, tie a row of other horses to them, and go off in the

dark of night to the border. Zambrów was a strategic point for them.

It was possible to reach the border in one night. Here there were

large stables that belonged to the three brothers B. who owned

taverns. From time to time, the gangsters would lodge there, posing

as horse merchants. The local Polish community put pressure on the

Zambrów Jews, the owners of the taverns, to maintain silence. Also

the gabbaim of the community, who were responsible for the

deeds of their brethren, had to keep quiet. For this reason they to,

were arrested, but later on they were released.

However, for purposes of enhancing

their prestige, the criminal police added charges of ordinary theft

and murder to the charges against the gangsters, which had been

discovered and were incidentally recorded in reporting to the

authorities. It was said that horses had been stolen from a nobleman

near Zambrów, night after night, the Chief of Police said to the

nobleman: leave two good-looking horses in the stable tonight, and I

will hide in the haystack and will harass the thieves. So that

night, they not only stole these horses, they also stole the jacket

and sword of the secret agent.

For many years, the family of horse

traders that was sent to Siberia were called the 'Siberians, when

they came back from Siberia. In town, the truth was known, and the

dignity of those who were mixed up in this trial was not impaired.

So this is the story of the Zambrów

Gangsters, who marked our town with a less than stellar reputation

in the larger world.

After the [First Great] Fire, the town

got itself back up on its feet. The marketplace and the surrounding

side streets were quickly rebuilt. Instead of single small houses,

two-story houses were built. Several tens of additional Jewish homes

were added on ulica Ostrowska, on

ulica Bialostocka and ulica Cieciorka. Commerce

flourished, and the houses of study were full of worshipers. Zambrów

became the principal city of all the surrounding settlements.

Zambrów looked after the Jewish settlement in Brzeznica, in Szumowo,

etc.

Approximately four hundred Jewish

recruits were installed in Zambrów, and the town had to provide for

their kosher food., for their Sabbath, and Festival holidays, and

other matters pertaining to their Jewish faith. In general, it was

the military that contributed most of the income to the town. During

the summer, the Jewish small businessmen and tradespeople would be

drawn to the summer residence in Goszerowo, where the Zambrów

soldiers would spend the summer in camp. Maneuvers would frequently

be conducted and at that time, the town was packed with soldiers

and the stored were full of them. The town considered itself to be

entirely Jewish and was enclosed in an eruv,23

thereby permitting the town Jews to carry a handkerchief, or a

prayer book on the Sabbath, or to carry a

cholent, etc., until the Second Great Fire arrived, which broke

out on Saturday night, May 1, 1909.

About five hundred Jewish houses were

burned down. The misfortune was laid at the foot of the Zambrów

Christian Fire Fighters Command, which was anti-Semitic in its

sentiments. Once again, the town got back on its feet quickly and

became much more beautiful and prosperous than before. Ulica

Kościelna, with its sidewalks and pretty businesses, became

equivalent to what one would see in a large city.

|