|

Editor’s Foreword

After

several years of strenuous effort, the Yizkor Book about our

tragically destroyed home town of Zambrow finally is appearing.

Many strands

tied me all of my life to Zambrow, the town where I was born, more

than sixty years ago. I left it as an 11-year-old boy. I have

wandered a great deal since that time, and absorbed both familiar

and unfamiliar cultures – however, I have never forgotten my ‘Old

Country’ [home] with its Mameloshn1 culture. And

when Zambrow was so tragically wiped off the Jewish vista, it came

back to life again before my eyes, as a ‘spiritual’ Zambrow, and a

mysterious impulse began to nag me: get up and set down a spiritual

memorial for Jewish Zambrow! Record its history, its balebatim2,

and Jews who were common working people, her clergy, and those

activist Jews in secular life, scholars and simple people who just

recited Psalms, the synagogue and the houses of study, societies and

institutions. And if not now – by the last generation of those

personally from Zambrow – it will never come to pass. And so, I took

to the creation of the book with affection and longing, but the task

was a difficult one.

The memorial

has been placed, the book has already appeared. Regrettably, I was

not able to accomplish this for everyone:

Zambrow was

a small shtetl. There is practically nothing written about it

in Jewish and non-Jewish writings. Also, our ‘old home’ is mentioned

very infrequently in newspapers. And the municipal archives no

longer exist, and in the best circumstance they are no longer

available at our disposal. The older people, who were eye witnesses,

and can tell us [what we want to know] – have passed on a long time

ago. So we turned to our landsleit, older and younger, who

remember, and are capable of writing. But few volunteered – not

believing that anything would come of this.

What

remained was for us to fashion something about the history of the

town from remnants and old documents and from glimpses and minor

observations, going from point to point, item to item, to create an

organized list of the history of the town and its Jewish settlement.

And who is to know how many facts disappeared from our view, and how

many personalities were forgotten by us? We could not resolve this

issue. Despite this, we established this initiative, and the book

was published, in which the entire town passes before us as if in a

play. So, here and there, personalities and facts are perhaps

missing. Despite this, we put together a book about our Jewish

Zambrow, from its inception to its destruction.

We have

written this book in both languages, as our traditional literature

had been written at one time: ‘The Holy Tongue’ (Hebrew) and

‘Ivri-Teitch’ (Yiddish), together. The reader will have to make

an effort to find the translation on the second side – but in this

way we have done justice to our two languages: The Mother-language

(Yiddish) and the Father-language (Hebrew). We are providing a short

overview in English – let the grandchildren of those from Zambrow

come to know something about their grandfathers and grandmothers...

In a few places, we shortened the text in one of the languages, or

made use of only one of the two languages. We took care to preserve

the Zambrow Yiddish idiom3 as far as possible.

We have been

able to provide somewhat more in the line of pictures, as much as we

could, and as much as we had in our ambit, and as far as they were

in good condition. We incorporated into the book more that two

thousand images of the Jewish Zambrow Heder schoolchildren,

with their Rebbes and teachers. We incorporated several

hundred young people – pictures of societies and the committees of

parties, to the extent that we had them, making no distinction with

regard to party and political persuasion. We have also incorporated

a few pictures of townsfolk. For the majority of them, their sole

remembrance is to be found in this book.

We have

included things about the ambience of the town – this freshens our

memory, and links us all the more so to the cradle of our childhood.

Regarding

the eve of the destruction of Zambrow, and the Holocaust itself, we

exclusively relied on primary sources: from letters and eye-witness

accounts. Regardless if certain details are not consistent, dates,

etc., we have included everything, just the way it was recalled.

The material of the book can, in part, serve as historical sources

for Jewish life in Poland, of the last century in general, and of

the last several decades in particular. To this end, we have

included Zambrow into the golden chain of Polish Jewry, that was

uprooted by the German Amalek4 with its

accomplices.

It is my

responsibility here, to bring to mind, with gratitude and respect,

those numbered few who helped me with my work:

My friend, Mendl Zibelman (son of R’ Israel-David, Miami, Florida),

adorned this book with his inspiring memories. Professor Ber’l Mark

(Warsaw). Chaim ben David (Moshe-Aharon the Painter’s son, Detroit –

Israel). Zvi Zamir, Sender Seczkowsky (Itcheh the Painter’s son,

Tel-Aviv), Joseph Srebrowicz (Tel-Aviv), Joseph Jerusalimsky

(Ashkelon), The three Yitzhaks: Golda, Golombeck, and Stupnik, and

Moshe Levinsky – smoking embers snatched from fire and sword. And

last, but not least: My beloved father and teacher, Israel Levinsky

k”z, who did not write just a little for the book, but was not

privileged to see it come to fruition. Chaim Zur (son of Fyvel

Zukrovich, Ramat HaKovesh) designed the cover of the book, and drew

a map of the town from memory.

Three landsleit-organizations seriously participated in the

material expenses for the book: The Organization of the Zembrover

Society in New York, with its brother societies, headed by our

American ‘ambassador’ Joseph Savitzky, Yitzhak Rosen, Isaac

Malinovich (who gathered untold tens upon tens of pictures for the

book), Eliezer Pav and many others. With their broadness of heart

and full and open hands, the book became a reality.

Our landsleit in Argentina, led by the prematurely deceased

Ch. Y. Rudnik k”z, and to be mentioned for long life: Boaz Chmiel,

Joseph Krulewiecki, Yaakov Stupnik, Crystal, and many others – also

contributed to the book, and from time-to-time offered us

encouragement.

The

Organization of Zembrover in Israel, headed by the comrades: Zvi

Zamir (Hershl Slowik), Zvi ben Joseph (Hershl Konopiateh), Pinchas

Kaplan, the sisters Malka and Liebehcheh Greenberg, Leib Golombeck,

etc. They were the ones who led the creation of the book.

At the end:

Our small Zambrow families: In Mexico City, our comrades Chaim

Gorodzinsky, Yitzhak Rothberg, and others, and in France – Esther

Smoliar-Shlieven, and others.

All – Those

whom I have mentioned here, and those that I have perhaps forgotten

– may they be designated for good, and may they all bless themselves

with this book, that they cooperated in producing.

Yom-Tov Levinsky, Tel-Aviv

A Word from the Zembrover Organization in

Israel

The

Pinkas5 of Zambrow is edited and partly written by

our landsman Dr. Yom-Tov Levinsky.

A full eight

years have gone by since we decided to publish a Yizkor Book

about our Zambrow. In that time, we made strenuous efforts – but I

will not exaggerate when I will say that were it not for the editor,

Mr. Levinsky, the book would not have appeared: his phenomenal

memory made it possible to dig up from the past, and from forgotten

memories, men and facts, incidents, ways of life, the history of

families and other interesting things that ran their course in

Zambrow years ago. He searched, rummaging relentlessly, day and

night, and uncovered sources relating to the history of the town,

especially in the Hebrew newspapers of the times. He looked after

giving a voice to the landsleit in Israel, and the world at

large, especially those not inclined to take pen in hand,

encouraging and directing many in writing. An now, when the book

lays before my eyes, and the book of some 700 pages – beautiful

Zambrow passes before my eyes like a panorama: The streets and

byways of the shtetl, the Pasek6 and the

marketplace, its synagogue and houses of study, its clergy, the

Rabbis, Dayanim7 and Shamashim8;

and community political organizations, their leaders and hordes of

members; HeHalutz; prominent families who were so extensively

branched out, porters, wagon drivers, storekeepers and bakers, the

erudite bookseller Abba Rakowsky, and other prominent townsfolk, the

young schoolchildren and the elderly – hundreds of pictures, that

preserve every aspect of the town of those days, up to the

Holocaust. Many pictures, that were donated, were gotten only with

great difficulty in Israel and the United States, It seems to me

that, the whole town, as it existed, appears in the book. Not a one

has been overlooked.

The special

chapter about the destruction of Zambrow during the Holocaust is

written by Yitzhak Golombeck, one of the living [eye]- witnesses,

and a survivor of Auschwitz, and with him: Yitzhak Golda, and

others. Read it with an ache in your heart, but with respect and

recognition for our heroic martyrs, parents, brothers and sisters, –

from the beginning of the predation, the concentration in the

ghetto, to the extermination – you hear the reverberation of the

cries of those who were taken to slaughter, and you breathe in their

final minutes.

The folklore

pages of the book have special meaning. The editor has incorporated

words and expressions from Zambrow, which in part, we still use to

this day, in our daily affairs. Special chapters are dedicated to

education, political movements, and social assistance. In addition

there are descriptions of various type of Zambrow folks, writings

about the way of life, etc. Using this, he truly takes us into the

‘old home’... he deals here with the young people in the synagogue,

societies, work and industry, mutual aid, etc. The Zambrow societies

of all countries are described, their activities on behalf of the

local landsleit, and for their brethren in all corners of the

world. I will not exaggerate when I say that our Yizkor Book

will be one of the best of those that have already appeared, up till

now, and we may take pride in it.

Our ‘old

home,’ Zambrow is no more. The sacred bones, and remains of our

townsfolk have not been given a proper Jewish burial. Their remains

lie in the great mass graves in the forests of Szumowo and [Rutki]-Kosaki,

and in the ash heaps at Oswiecim. In the town, only Christian

peasants go about, who have seized Jewish assets, and no one remains

to take it back from their hands. Only a few faded headstones remain

in the cemetery, among the overgrowth and thorns, that indicate, at

one time, there was a Jewish life and a sizeable Jewish city.

This book

is, and will remain for generations to come, the truest memorial for

Jewish Zambrow. In it, we have preserved the memory of the lives and

the echo of the suffering of the Jews that no longer exist. It is

here that we have put a ‘Place and a Name9’ to

their light and their memory.

We therefore

wish to thank our brother-organizations in The United States, with

our comrade, Joseph Savitzky at its head, and in Argentina, and so

forth – for their material help, and great interest in the book. We

thank those who took part in the book by sharing their memories. We

thank all of our landsleit in Israel, and outside the Land,

and especially our friend Zvi ben-Joseph in Israel, who gave so much

of his energy and attention to the book. All of, who participated,

encountered difficulties with all of the obstacles that lay in our

way, and despite this, we produced a book that is both pleasing and

substantive. At a suitable time, let our townsfolk consult it, and

let us leave thereby, a legacy to those children who will follow us,

about the eternal way of life of our people, who lived it in our

shtetl of Zambrow

All, all of

you, consider yourselves saluted, and blessed.

In the name of the Zembrover Landsleit-Organization in Israel

Zvi Zamir (Slowik), Chairman

The Historical Pages

By Dr. Yom-Tov Levinsky

Dr. Yom-Tov Levinsky

A. When Did Zambrow Become a City?

A city does

not simply spring into being all at once. First, a small settlement

appears, afterwards a village, and later, when the village spreads

out, it becomes a town. This certainly must have been the case with

Zambrow. It was a small village for many years, and after that a

village. It was first, only in the second half of the 15th century,

that it grew large, and the residents demanded from the authorities

the Mazovian Principality that they grant it the status of a city.

Their request was accepted, after it was certified that Zambrow

satisfied all the criteria to be considered a city.

In the year 1479, 5239 after creation, the ruler of Mazovia, who

ruled over the Plock Region, the Prince, Janusz II, was persuaded to

grant the Zambrow settlement the right to call itself a city (Zombrow/Zomrow)

And from that time on, to enjoy all the privileges of a city.

Several years later, the residents of the city again petitioned on

the basis that they did not have any regularly scheduled fairs and

the merchants of the surrounding towns avoid coming to Zambrow, and

therefore compel the residents to travel to buy goods at the market

fairs of neighboring cities. Then, Prince Janusz II officially

designated this privilege for Zambrow, even nominating it to be a

Powiat (a central city). At this time, it was already being called

Zombrowo (Zambrowa).

B. The Privileges of the City

The ruler

granted the right to the city to conduct two fairs a year. One on

June 24 (Czerwiec), on the day of St. John (Swiaty Jan) and the

second – on September 21 (Wrzesien), meaning: one fair before the

harvest, and the second after the harvest. The populace needed to

wait three-quarters of a year until the new fair. First, 44 years

later, when the city had developed further, and a number of villages

became affiliated with it, in the year 1523, the government of the

Kingdom of Poland, to which Mazovia de facto already belonged at

that time, decided to designate four additional fairs for the year –

a total of six fairs. This was a symptom of a progressing city. With

ceremony, it was, once again, designated as a Powiat. In 1527, when

Mazovia officially became part of Poland, the privileges of Zombrowo

were again certified.

In the year

1538, Zambrow was destroyed by fire and sword. The war between

Poland and Prussia, by happenstance, took place in Zombrowo. The

Prussian military fortified itself in this place, afterwards called

Pruszki. The Poles – were on the other side. The city, which was in

the middle, was meanwhile burned down, and the residents – all fled.

In the year 1575 – Zambrow belonged to Ciechanow, where the castle

of the ruling noble was located.

The new

Polish King, Zygmunt I, son of Casimir IV, heartily received a

delegation of balebatim from Zambrow, and listened to their

complaints, and took a hand in their plight, promising to alleviate

it. There were no Jews among them. He lowered the taxes of the city,

annulled all of their debts, and renewed the privileges of the city,

that had been lost when the original copy of their official charter

was burned. The members of the delegation certified the details of

the burned declarations by oath.

C. The First Sign of Jews

Were there

Jews already [present] in Zombrowo? It was not made clear to us

whether there was already an established Jewish community in the

city, but what is known to us [is]: The city government turned to

the King, Zygmunt I10 to have him permit the movement of the market

day from Wednesday to Thursday, so the Jews would be able to

purchase their requirements for Shabbat, the Jews being present in

the area in not insignificant numbers. However, a number of

incidents took place in the city that caused its decline. It is

possible to see this from the revenues [sic: of the market days}: in

the year 1620 those revenues from meat, honey, liquor and grains

were close to 508 Florins (approximately like Gulden), and those

[same revenues] in the year 1673 had fallen to an income of 35

Gulden. The area of the city, and its environs reached 52 voloki

(the volok was 20 marg11), and only 9 of them constituted land that

was being worked, with 49 volok remaining fallow.

D. The Name of the City

We have

already documented the fact that the name was first written as ‘Zambrowo,’

and later as ‘Zombrow.’12 Stanislaw August II who ruled from

1764-1795, called it ‘Zembrow’ (according to ‘Starozhitnya Polska’

530-523). In the 19th century, it was already being called ‘Zembrow,’

and in Russian, ‘Zambrow.’ The Jews always called it ‘Zembrow’

(according to Pinkas Tykocin13), and in the last century – ‘Zembrowo.’

In the list of the Jewish census in Warsaw, from the year 1781,

there are listed, among others Jews that lived in Warsaw, but that

came from ‘Zembrowo.’ One individual registered himself as follows:

‘I come from Zembrowo,’ and another, ‘from Zambrow...’

The name

Zamrow-Zambrow appears to be derived from the small river, Zambrzyce

which is beside the shtetl, or perhaps the other way around –

does the river take its name from the shtetl? One is led to

believe that in the 13th or 14th century, there was a Prussian

colony of the Teutonic Knights (who were crusaders). Here, a summer

vacation spot was located for the German rulers, because the

location was encircled by forests. It was called the Sommerhof –

which [it is believed] that the Poles later modified to Zomrow and

according to the linguistic rules, either a ‘b or a ‘p’ gets

inserted between the ‘m’ and the ‘r,’ for example, Klumar –

Klumfurst, Kammer – Chamber, Numer – Number, etc. [In this way]

Sommerhof became Zombrow – Zambrow.

E. the Political Situation

Zambrow is

administratively divided into two parts: the city proper (called the

Osada in Polish) and the Gmina (the greater vicinity). The city

itself was small, encompassing one market square (Rynek), from which

small streets emanated in all directions. The horse market bounded

the town on the west, and the ‘Poswiatne’ on the east.

The Gmina,

however, had under its jurisdiction, 20 villages and hamlets. By

1880, the Gmina had 44 villages under its jurisdiction, and numbered

12,154 souls. Jews also lived in those villages, some as tenant

farmers (pokczary, but the majority, up to about ten or more, were:

Gardlin (Galyn, the Bialystoker Road, where Shlomleh Blumrosen’s

brick works was located), Grabowka, Gorki, Grzymaly, Dlugoborz,

Wadolki, Wiśniewo, Wola [Zambrowska], Wiebrzbowo, Tabedz, Cieciorki,

Laskowiec, Nagorki [-Jablon], Sedziwuje, Poryte [-Jablon], Pruszki,

Konopki, Koretki, Klimasze, etc.

Zambrow

belongs to Mazovia, and independent, but poor land, which is rich in

water, arable land, forests, cattle and fish – but is

little-developed and stands at a low cultural level. After the

Crusades in Germany, from the year 1096 onwards, the local Jews

began to emigrate to Poland. In the 12th century – thousands

streamed here – thousands of German Jews. Thousands also took up

residence in Mazovia, in the older cities such as Plock, Czersk,

Sochaczew, Wyszogrod, Plonsk, Ciechanow, etc.

With their

full ardor, the Jews began to occupy Mazovia and industrialize it.

The lived here in tranquility, and were not subject to predation.

Only when Mazovia first began to draw close to Poland [proper] – did

limitations begin to be imposed on Jewish citizenship rights.

Nevertheless, Jews enjoyed the privileges in a special law for Jews,

‘Jus Judaicum’ (Privilegium Judaeorum). The Jews integrated

themselves well in local life, and the Mazovian laws, even calling

it ‘our law’ (Jus Nostrum). In the year 1526, Mazovia is integrated

into Poland, and they become one country. The Mazovian Jews now fall

under the laws and limitations that apply to Polish Jews.

F. Geography and Topography

From time

immemorial, Zambrow belonged to the Lomza Guberniya (Province), and

is counted as the second largest city according to its population.

At the end of the 15th century – Zambrow was officially a Powiat

(center). In the year 1721, the Polish Sejm divided the Lomza

Guberniya into two municipal districts: Zambrow and Kolno. The Chief

City Elder (Starosta), resided in Zambrow.

Zambrow lies

among the Cieciorki and Wandolki forests, among others, not far from

the famous forest area of Czerwony-Bor (about 13 versts from

Zambrow). And between the cities: On the east – Czyzew, which has an

important train station to Warsaw and Bialystok, Wysoka, and

Jablonka to the west, the train station Czerwony-Bor and Lomza, the

provincial capitol of north Bialystok and south Ostrow-Mazowiecka.

Three small

rivers ring the town: A. The Jablon – whose headwaters are in the

town of Jablonka, courses through Zambrow, flowing for a distance of

about 20 versts to Goszt. B. The Prątnik, which emanates from the

town of Prątnik, near Sedziwuje, and C. The Zamrzyce, which emanates

from Wiebrzbowo, and flows into the Jablon. Jablon (or Jablonka) is

the principal river of the area.

Following a

regulation promulgated by the Zambrow community, at the proposal of

the Rabbi, all of the little rivers were officially referred to as

the Jablon, in order to facilitate the preparation of ritual divorce

documents (e.g. a Get) in Zambrow: this is because the town river

has to be documented in the Get. The provincial leadership accepted

this proposal.

About one

verst from the town, to the east, the ‘Uczastek’ of the military

region is located. There were not few Jews who lived here, who made

a living from the military. They had their own Bet HaMedrash

there, two bridges –one of wood, and was on the Ulica14 Ostrowska, and

a concrete one on the Ulica Czyzewska – connecting the town to the

surrounding settlements.

G. Jews Build the City

The Jews

built out the market square (Rynek) and one after another, they

erected houses around the marketplace, opening stores, and in this

way worked over the center of the town, and took commerce and

industry into their hands. The gentiles concentrated themselves

around the horse market and the Poswiatne, and engaged in

agriculture. Zambrow had good drinking water from its streams. The

principal stream was behind the Red Bet HaMedrash, which

provided for more than half of the town. A second stream was on the

Rynek itself, and the water was obtained by a pump. Water-carriers

would also draw water from the river.

There were

two (Jewish-operated) steam-driven mills, one was a water-mill, and

4-5 Jewish manufacturing facilities. On the Ulica Ostrowska, near

the water, there was a large Jewish dye plant. On the other side of

the city – a large Jewish brick works (Gardlin). Jews participated

in small industry/business: distilled whiskey, made wine, brewed

beer and made kvass and soda-water. According to the census of 1578,

there were six distilleries and eight shoemakers, that also employed

workers, five butchers, and eight bakeries. Having about itself the

rich Jalowcowa forests, much beer was brewed, that was given the

name ‘Jawlocowca Beer.’ In the referenced year, in accordance with

the tax rolls, it was established that 241 barrels of beer were

brewed in Zambrow.

The city was

consistently ruined by fires, plagues, peasant uprisings, invasions

by the Tatars, Swedes and Prussians, such that, in the year 5560

(1800) it only had 81 houses in it, and a population of 564

residents. Part of the population lived in barracks, and they cooked

and baked under the open sky. In the year 1827, there were 91 houses

already (10 new houses in 27 years!) And the population numbered 88615

people. And it was at this time, that the Jewish initiative and

spirit of commitment to develop the city got started. In the passage

of 4-5 years, the entire Rynek was built up, with 30 new houses of

Jews. In each house, there was one or two stores. The city

established a cemetery, retained a Rabbi, built a synagogue, two

houses of study, a bath house with a mikva, established a

building for a religious court, founded a yeshiva and – Zambrowo was

a Jewish city.

In the year

1868, there are 1397 Jews in Zambrow, approximately 60% of the

general population. In the year 1894 – there are, already, 1652 Jews

in Zambrow. In the year 1895, at the time of The First Great Fire –

according to the newspapers – more than 400 Jewish homes were

consumed, among them, about 100 Jewish stores, and eating places,

and about 2000 Jewish residents were left without a roof over their

heads. The numbers – speak for themselves.

The Jews of

Zambrow had an interest in making the city attractive to Christian

worshipers, the lesser nobility (szliachta), peasants, and dyers,

who, in going to church, would along the way, buy all their

necessities. So, outside the city, there stood a half-built church

dating back to 1283. It became ruined and had been burned several

times. At the end of the 18th century, the Canon of Plock, Martin

Krajewski became the senior cleric of the Zambrow parish, and in

memory of his parents, he reconstructed a wooden church, with a bell

and a mortuary. The Christians in the villages would go to worship

in Szumowo, Jablonka, Sedziwuje, etc., so that in Zambrow, a larger

central church could be built, which could accommodate hundreds of

worshipers every Sunday. The old church stood at the west of the

city, beside the horse market, to serve the worshipers there. The

new church stood to the east, and attracted scores of peasants from

all of the villages, filling it on Sunday, along with the city

streets and stores...

Two years

after the fire, the number of Jews rose substantially, as seen in

the census of 1897, where in the Zambrow Gmina (including the

surrounding villages), there were 10,902 residents, among them 3463

Jews, nearly 32% of the general population.

H. From When On, Were There Jews in Zambrow?

The Market Place (Zambrow Rynek)

It is

difficult to answer this question. Jews were already in Mazovia, the

part of Poland where Zambrow is located, since the beginning of the

14th century. However, impoverished Mazovia did not have much

attractive power, and consequently, few Jews settled here. Apart

from this, the political situation was not conducive; there were

continuous invasions by the Prussians, and others, that destroyed

the land. It was first at the beginning of the 15th century that the

circumstances began to improve, with the Lithuanian princes16 Janusz

I, in Warsaw, and Ziemowit IV in Plock, who strove for peace, under

the aegis of Poland. Consequently, economic conditions also

improved. Fields and woods bloomed anew, fish and wildlife, leather

and hides, flax and wool, honey and oil, all developed, and the Jews

found an attractive location here. Cities were established here, and

therefore, for the first time, in the year 1471, we hear about Jews

in Lomza for the first time; the diocese of Plock spread its

ecumenical purview also to cover the Lomza district, and accused the

Scholastic, Stanislaw Modzielow of Lomza, in an assault on Jewish

merchants of Lomza and has him arrested.

I. Tykocin Protects the Zambrow Jews

Since the

year 1549, the Jews of Mazovia paid their national head taxes

through the ‘Va’ad Arba Aratzot,’ the Jewish Sejm, which was

required to present the kingdom with a specific sum of taxes on an

annual basis, which was collected in accordance with a set formula

from all cities and towns. Zambrow does not appear in this list,

because a Jewish community did not yet exist there. Tykocin, which

was one of the three central cities of Podlisze, and collected the

Jewish head tax from the residents of Lomza, Grodno and other

centers, imposed a levy on the surrounding small settlements, where

there was no community, and strictly demanded taxes, and regulated

issues between Jews and gentiles, and took care to assure that one

party would not unjustly take away the livelihood of the other, in

land leasing, and in liquor distilling, fields and gardens, milk and

cattle, mills, and the like. If there was a larger settlement – then

Tykocin would impose the mission on the community or on the

religious court of the shtetl, to the point that if a city in

the area was mentioned in referenced acts, for example, even one

that was as large as Bialystok, it was added to be ‘in the vicinity

of Tykocin, because Tykocin was the capitol city of the district up

to 1764, until the Polish regime dissolved the Jewish Sejm – the

Va’ad Arba Aratzot, which was a government within a government,

and adopted other, and better, means to collect more head taxes from

the Jewish populace. Also, afterwards, Tykocin continued to be the

chief city of the district. Regarding Tykocin, we know that in the

year 1676 (5436) the community adopted a resolution “under penalty

of excommunication consisting of seven decrees, and extinguishing

black candles, with trumpets and blowing of the shofar: that no one

has the right to raise either hand or foot to deal in strong drink,

not as a business or for sustenance, whether by license under the

government, as a tenant, under beverage-making duty, or

beverage-selling duty, etc., without the cognizance and express

permission of the community. Everything must first be presented to

the community, and its leadership, who must thoroughly and

completely examine it, without the presence of the petitioner.

Whatever they decide is to be recorded in the Pinkas of the

community (all this according to the Pinkas of the Va’ad

Arba Aratzot, p. 148, sign c”ba). The Pinkas of the

Tykocin community no longer exists, as was the fate of many of the

Pinkasim of other cities. However, in The First World War,

when the Jews of Tykocin were compelled to abandon their city – the

Pinkas was placed in the hands of the Rabbi of Bialystok,

Rabbi Chaim Hertz. His grandson, who is today a professor of Jewish

history at the University of Jerusalem, Dr. Israel Heilperin,

secretly made a copy of the protocols of the ancient Tykocin

Pinkas and in this way, managed to preserve them for posterity.

Among the protocols (which are still in manuscript form) we find the

name of Zambrow mentioned in isolated places, and we have made note

of them.

J. The Jews of Zambrow in the Year 1716

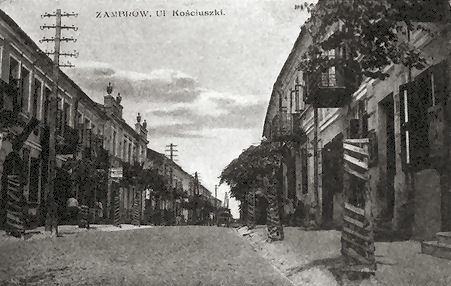

Ulica Kościuszki (Koshare

Road)

We now turn

back to Zambrow, as it was in those times. There is a theory that in

this location, there already was a small Jewish settlement in the

16th century, but that it was disbanded in response to the

residents, who had the had the discretion not to tolerate having

Jews in their city (de non tolerandis Juudaeis), as was also the

case in Lomza and other tens of cities and towns in Poland. We do

not possess any documents with which this can be established.

Zambrow was also not an important point and did not have any

substantial undertakings that would merit mention in government

regulations.

We are able

to extract from the Tykocin Pinkas that in the year 5476

(1716) there still was no Jewish community, despite the fact that

Jews lived here, and ran substantial businesses. On page 164, volume

748 of the Pinkas, it says: “income producing business and

the house where R’ Shmerl ben Yitzhak lived, passed into the hands

of the brothers Yehuda and Shmuel, the son of the previously

mentioned Shmerl and they are entitled to right of enjoying its

benefits in perpetuity. This remains the case even if there is a

change in city Elder, or the Elder’s death, or if a gentile will

have possession of the business for a number of years, and if

someone wants to repurchase the business from gentile hands – he has

no right to do so, because it belongs only to Shmerl’s children.

This was approximately in the year 1716.

On page

271,volume 796 of the year 5476 (1716) it is again told that Yitzhak

son of R’ Yaakov of Jablonka bought the franchise (the right of

Furmanka – use of a wagon) to collect ‘franchise taxes’ from the

Zembrowski Powiat in the Lomza Guberniya. All the franchise

promissory notes from the previously mentioned Powiat, are his

prerogative in perpetuity, even in the event that he should no

longer reside in the Powiat.

K. Zambrow Has No Control over Cieciorki

In the same

Pinkas, page 797, of the year 5476 (1716) there is a

reference to a ‘sharp discussion’ that took place between Tykocin

and the Jews of Zambrow, with regard to the control of the liquor

franchises in Cieciorka. The noble of that region has constructed a

distillery on his estate, and leased it to the Jews. As was the

custom, a Jew could not independently come to lease such a facility

– only with the facilitation of the Tykocin community, could that be

accomplished. And here, the community permitted the lease to go to

one, R’ Jekuthiel. The Jews of Zambrow argued that they had a prior

right to the lease, based on proximity.

In the same

year, and on the same page, it is recorded that the lease to the

distillery of Cieciorki, which is near Zambrow, was sold by the

Dozors of the community to Mr. Jekuthiel son of R’ Mordechai, and

‘no Jew may approach there (to infringe on his territory) because it

belongs to him, in perpetuity” – after it was certified that

‘Cieciorki is further from the boundary of Zambrow, and that is why

it was sold in perpetuity to R’ Jekuthiel.’ This means: the Zambrow

community has no say in whether the distillery is leased to a Jew

from Zambrow or a Jew from Jablonka, because Cieciorki is far from

the Zambrow border and therefore does not belong to it.

L. To Whom Does Sedziwuje Belong?

It appears

that the previously mentioned R’ Shmerl was a businessman on a large

scale, and had leases on businesses not only in the city of Zambrow,

but also in the Gmina, meaning the larger district encompassing

Zambrow and its surrounding villages (Wola Zambrowska), Nagorki, Klimasze, who according to all our information, were attached to

Zambrow, and whoever had a franchise for a certain way to make a

living in Zambrow – that privilege extended to the villages.

Sedziwuje was excepted because allegations were made that it was far

from the Zambrow city limits, and is therefore not included, and as

a result a local resident has the right to take the franchise for

this village.

In protocol

number 784 of the same Tykocin Pinkas, we read:

‘The

decision of the chief Rabbi, Rabbi Yehuda, son of the [former] chief

Rabbi Shmeri’ Zembrover, that all the villages in the ambit of the

city of Zambrow are under his jurisdiction, and no man has the right

to infringe upon that right, as if it were in the city of Zambrow

itself, and within its borders. And these are the villages, whose

status was clarified as being within this ambit: Sedziwuje, Wola,

Nagorki, Klimasze. However, a protest went out regarding Sedziwuje

which is further from the borders [of Zambrow] and an outcry was

made to settle the matter by measurement, by someone trusted by us,

and for as long as the matter is not clarified, the village will

remain under the jurisdiction of the [Zambrow] community.

Tuesday, 14

Iyyar 5476 (1716)

This means:

The previously mentioned Yehuda son of R’ Shmerl, one of the two

brothers who inherited the franchise for the spirits business in the

city of Zambrow from their father, and no one is permitted to

infringe on their franchise in the city – registered a complaint in

the religious court in Tykocin, that other Jews were grabbing pieces

of his income, and violate his right. because they have income from

the nobles, part of whose assets is from Zambrow. The defendants

defended themselves with the excuse that they transact business only

in those villages that are not under the control of Zambrow. A

special session was called to clarify this matter. All the

previously mentioned villages were measured, to determine if they

were close to Zambrow, from the border to the city. They discovered

that the villages of Sedziwuje, Wola, Nagorki and Klimasze were

close to Zambrow, and therefore are included in its ambit. For this

reason, no one may infringe on the franchise of R’ Yehuda son of R’

Shmerl. The protest of the accused is just, in that Sedziwuje is

more distant from the Zambrow border. However, their complaint was

not yet researched enough, and ‘calls to attain the truth’ by means

of measurement. Because of this, Sedziwuje was declared to be a

‘free-city;’ it did not belong to Zambrow, but was not considered

out of Zambrow’s ambit. In the interim, the Tykocin community will

manage the village, and will designate who may practice the

businesses and estates of the nobles of Sedziwuje. The judgment was

carried out on 27 Iyyar of the year 5476 (1716).

A short time

after this, we read, in volume 785 of the Tykocin Pinkas

(page 269) that the religious court determined that the village of

Sedziwuje is at a further distance from the border of the city of

Zambrow, but not more than one quarter of a verst. This became clear

through the testimony given by someone who had personally measured

the distance. The judgment was carried out on Monday, 2Elul, of the

year 5476 (1716) and the protocol was signed by: Abraham Auerbach,

Yitzhak son of R’ Abraham, and Gedaliah son of Menachem the Kohen.

The

previously mentioned R’ Yehuda son of R’ Shmerl appears not to have

remained silent, and complained that one quarter of a verst was

hardly a distance that was significant, and that he alone, had the

right to [the business of] Sedziwuje, and that right was his as a

citizen of Zambrow, and did not belong to anyone else. This matter

dragged on from the month of Elul 1716 [5476] to Iyyar 1717 [5477].

And finally, in the end, a judgment was promulgated on the basis of

research and investigation, and credible witnesses that Sedziwuje is

‘far’ from Zambrow and does not belong to it, therefore it is under

the aegis of the Tykocin community, and that the owner of the

Zambrow franchise has no longer any basis for dispute and complaint

against the village, [written] Wednesday, 16 Iyyar 5477 (Lag B'omer

eve, 1717). Signed by Yitzhak ben R’ M”Y.

We did not

find anything else in the Tykocin Pinkas about Zambrow. We

can, however, infer with great confidence, that if there had been a

community in Zambrow with its own religious court building, that

Tykocin would not have involved itself in the issues of the city.

Zambrow would have independently defended its own interests, even if

it would have had to secure the concurrence of Tykocin.

M. The Founding of the Chevra Kadisha in

the Year 1741

The cemetery

at Jablonka served Zambrow also, as well as other towns in the area

including the villages of Nagorki, Pruszki, etc. At the beginning,

the bodies of the deceased were brought to Jablonka, by wagon, as

they were. The Chevra Kadisha of that town then dealt with

the bodies – subjecting them to ritual purification, dressing them

in burial shrouds, and interring them. However, this was not out of

respect for the deceased – having to leave him for a period of time

without undergoing purification, but this was the custom in the

smaller settlements. When the settlement at Zamborow grew more

populous, it was decided to establish a Chevra Kadisha here,

that was to deal with the deceased in that location, and to bring

him already purified to Jablonka to his final resting place. As is

recorded in the Pinkas HaYashan [The Old Folio]

(according to the eye witness R’ Yehoshua Gorzelczany) – the

Chevra was established on 17 Kislev 5501 [Tuesday, November 25,

1740].17 It seems that the founding was accompanied by a festive

banquet, because the above date is the day of the Chevra

banquet in several [sic: neighboring] communities. Because the

simple goal of the Chevra, the “dirty” work, was – the

digging of the grave, and performing the burial – that was done by

the men of Jablonka, the men of the Zamborow Chevra permitted

them to add a condition in the Pinkas: whoever is not

knowledgeable in the study of a chapter of the Mishna –

cannot be a member of the Chevra Kadisha.18 In a similar

fashion, the honorific, ‘Morenu’ [Our Teacher] that is added

to one called for a Torah aliyah, was given to a man only by

the Chevra. The heads of the Chevra were learned men,

and it was possible to establish who was a scholar, and rightly

could be called: “Let Our Teacher R’ So-and-So the son of

So-and-So...,” and from whom to take away the title of ‘Morenu’

if it was improperly bestowed. From this point in the Pinkas,

it is possible to easily infer that these were learned Jews. The

Chevra Kadisha was a catalyst to the formalization of a

community, with all of the requisite appointments, and that did not

tarry in coming.

N. By 1767 There Still Is No [Jewish] Community

On March 21,

1767 (20 Adar 5527) the government commission of the royal treasury

(Kommisja Rzeczypospolitej Skarbu Koronnego) designated those

communities that now belong to the Tykociner region, with regard to

the level of taxes and the collection from both. Nineteen towns are

enumerated there: Augustow (Jagustowa), Boczki, Bialystok, Goworowo

and its surroundings, Goniadz, Wizna and its surroundings, Zawady

and its surroundings, Jesionowka, Jedwabne, Loszyc, Niemirow, Sokoly,

Sarnak, Konstantynow, Rutki and its surroundings, Rostki and its

surroundings, and Rajgrod.

Zambrow,

which is not far from Jablonka, and Rutki are not in the list! And

yet, we know from the dispute between Yehuda son of R’ Shmerl and

other lessees, in connection with the rights over the Zambrow

[liquor] franchise, Tykocin got involved and decided who was right.

[We deduce that] Zambrow was, indeed, under Tykocin tax control.

This means: Jews were living here, but not organized into any sort

of a community, without a Rabbi, without a mikva, and without

a cemetery.

It is only

first, at the beginning of the 18th century, that the history of the

[Jewish] community in Zambrow begins. The original settlement was in

the villages of Pruszki and Nagorki. The distance between these two

villages was not great, and it was there that a Bet HaMedrash

was built, that also served as a Heder for the children.

Older children were sent for education to the surrounding towns:

Jablonka and Sniadowo. Sniadowo has a reputation as a large Jewish

community, and its Rabbi even had aegis over Lomza, which at that

time, still did not have its own Rabbi, and not even a bath house.

(According to Polish municipal regulation, it was necessary to have

a special concession for a bath house). The Jews of Lomza, from one

side, and the Jews of Zambrow from the other, would travel or walk

on Friday, so... as to go to Sniadowo to bathe, and wash themselves,

get their hair cut, and sometimes be cupped or have blood let – all

in honor of the Sabbath.

O. The First Cemetery – In the Year 1828

Ulica Wodna (Wodna Street)

The number

of Jews, who took up residence in Zambrow proper, grew larger and

larger. They observed that it did not make sense to go from Zambrow

to pray at the Bet HaMedrash in Pruszki, so they formed their

own prayer quorum in Zambrow and two Torah scrolls were brought in

from Tykocin, borrowed for a short period of time. The Jews of

Zambrow set about having Torah scrolls written for themselves. The

settlement in Pruszki supported its existence, and remained

connected with the Zambrow Jews, as if they were one shtetl.

An incident occurred where a Jew in Zambrow died, and it was

necessary to have him taken for burial to Jablonka, by way of Ulica

Sedziwuje. The weather was bad – with heavy rain, and the road was

covered in mud, rivulets of water and potholes, because no paved

road existed there yet at that time. Therefore, it was necessary to

defer the funeral to the following day, and the day after, and this

was considered to be a great offense to the deceased. So, on

Saturday night, the Jews of Zambrow and Pruszki came together in an

assembly, and decided to create their own cemetery, on the way that

was, indeed, between Zambrow and Pruszki. R’ Leibeleh Khoyner, the

ancestor of the Golombecks, then donated a parcel of land and with

ceremony, it was decided to step up to the preparations: obtaining

permission from the authorities and indeed, also the concurrence of

the Chevra Kadisha in Jablonka, which each year demanded a

certain stipend from the Zambrow Jews towards the upkeep of their

cemetery, and the expenses of the Chevra [Kadisha]. A

liberal wind was blowing through Poland at the time, under Russian

rule. This was evident in the relationship of the Poles to the Jews,

in Lomza, the provincial capitol, from which the permission was

supposed to come. When the permission arrived, they began to cordon

off the field, and build a small structure for purification of the

deceased bodies. In the year 1828 (5588) the first cemetery was

dedicated.

The

community in Lomza was established anew in the year 1812, under the

influence of the spirit of Napoleon, who created the slogan among

the Poles, with regard to the Jews: – Kochajmy się, meaning, ‘Let us

love one another!. In 1815, Poland came under Russian rule. The

Russian authorities wanting to disrupt the unity among the Polish

population, removed many of the Polish limitations placed on Jews.

Despite this, the ‘Polish Kingdom’ under the Russians, resisted

this, and in the effort of a delegation sent before the regime in

Warsaw, in the year 1822, they succeeded to create anew, a ghetto

for the Jews, and limit their rights in Lomza. This was also the

case in Ostrolenka, and other places. It was first, in the years

1827, 1828, that Poland secretly began to prepare for its first

uprising (powstanie) against Russian rule (1831). It was necessary

to co-opt the Jews, and because of this, liberal winds began to blow

in Poland. It was therefore not difficult to establish a Jewish

community council in Zambrow. The Jews of Zambrow, at that time,

actually favored Poland, and were patriots on its behalf, even in

the uprising of 1863.

The

Chevra Kadisha grew and reorganized itself. A Pinkas was

initiated. The first Gabbai was the father of R’

Chaim-Pinchas Sheinker. Later Gabbaim were: Monusz Golombeck,

Shmueleh Wilimowsky, Binyomleh Golombeck, Abraham Moshe Blumrosen,

Abraham-Yossl Wilimowsky, and Yankl Zuckerowicz. Zuckerowicz was the

last Gabbai. The Nazis drove him to Germany, and tortured

him. When he returned exhausted, at the end of 1939, under the rule

of Russians, he collapsed and died.

Of the

martyrs, the names of the following are recalled: Abraham-Moshe and

Wolf-Hirsch Kuczapa, his son, El’yeh, Israel-David Zibelman, Mottl

Melsheinker, and Yitzhak the Dyer.

Approximately in the year 1890, the cemetery was filled to capacity.

The community then purchased a new location for a new cemetery,

which bordered on the old cemetery, and appeared like an extension

to it. It is told that a question arose among the Gabbaim at

that time, what is to be done with the ‘Ohel’ (The small

building for purification of the dead): should the old one remain in

place, which will now be at the [extreme] end of the new cemetery,

and the deceased will have to be carried through the cemetery to be

purified, over all of the graves that will, in time appear – or

build a new ‘Ohel,’ at the entrance of the new cemetery. R’

Shmueleh Wilimowsky said that the Ohel should remain in its

old location, and all that is needed is to re-build it and enlarge

it. Monusz Golombeck argued – that it makes better sense to have it

at the entrance, so that it will not be needed to carry the deceased

for a long distance, if it should be on a rainy day or during a

snowstorm. To this end, he proposed with humor: we are not going to

live here forever. In a hundred years, we are going to be buried

somewhere here, in a respectful place, at the front – as Gabbaim,

and in the coming generation when the cemetery will be full of

graves, and the members of the Chevra Kadisha will exhaust

themselves by carrying the deceased for such a long distance – they

will point to other graves on their way through, saying: here lie

the elder sages of the community, who lacked the common sense to

build the Ohel at the entrance, and put it so far away... [at

that time] will it be pleasant for us to hear such talk? When no

good will be said about us at the entrance, at least we will not be

in a position to hear this embarrassment... At this, Shmueleh

Wilimowsky laughed heartily, and agreed to what R’ Monusz proposed.

In the

government regulation about having their own cemetery, they already

had incorporated the right to create a Jewish ‘community’ in

Zambrow. And this did not take very long. The communal statute was

declared in the same year.

P. The Synagogue and Houses of Study

|

The Synagogue

|

|

The Entrance of the Synagogue

|

At first,

prayer was conducted in small quorums. In general, the town

consisted of small, wooden buildings, with straw roofs, and, without

making any comparison, even the church was made of wood, just

outside the town, not far from the horse market.

One of the

wealthy balebatim, R’ Leibeh, the son-in-law of El’yeh Katzin,

built the first building on the marketplace, and opened a very large

tavern there. He was schooled in Kabbalah, and a very decent Jewish

man. R’ Leibeh died suddenly – while still young. His young widow,

‘Rosa the Tavern Keeper’ or ‘Rosa of the Building’ gave over part of

her house to be used as a Bet HaMedrash, and this was the

first house of study in the shtetl.

They were

not, however, content with this: the town needed a synagogue.

Accordingly, a collective action was taken. Balebatim bought

‘places’ even before the synagogue was built, and up front they paid

a larger amount of money – for the good of the building. R’ Monusz

Golombeck donated the parcel which stretched past his yard in the

direction of Ulica Lomzynska, for the synagogue. The provincial

engineer permitted a street to be cut between his house and the

synagogue.

The

synagogue was constructed of stone and mortar, made of strong

bricks, and stone walls. At the beginning of the construction, the

history of the synagogue building was written down on parchment, who

donated the parcel, and who made contributions to the building fund,

and it was sealed well in an earthenware pot, and imbedded in the

foundation19. When the foundation was torn apart in later years, at

the time the new synagogue was built, it was found – it was re-read,

and once again, imbedded in the foundation.

After the

construction of the barracks, when the town had grown by several

hundred new worshipers, and the synagogue became crowded – it was

decided to build a large Bet HaMedrash. A ‘dispute’ arose in

the shtetl: the grumblers complained: it is necessary to

build a stone Bet HaMedrash, on the other side of town, on

the way to Cieciorki, so that it would be nearby for those that

lived far off. The ‘Golombecks’ argued: we don’t have to be

pretentious, and if the synagogue is made of stone – the Bet

HaMedrash should be made of wood, since this is the way things

are done by Jews.

Until the

time Monusz Golombeck turned over his parcel, which bordered on the

synagogue, and wood was procured, and boards were carpentered, and

the wooden study house started to go up slowly, beside the

synagogue... at which time Shlomleh Blumrosen and his partners

donated ten thousand bricks from his brick works, Herszak Bursztein

donated a place and a stone Bet HaMedrash was erected. It was

at that time that they began to call [them] the ‘Wooden’ Bet

HaMedrash and the ‘Stone’ Bet HaMedrash, or the ‘New’

Bet HaMedrash. During the time of the First Great Fire of 1895,

the wooden Bet HaMedrash was consumed along with the

synagogue. The stone Bet HaMedrash remained intact. In place

of the wooden synagogue, a stone synagogue was erected already, in

about three years time, made of red brick, in accordance with the

initiative of the ‘forthcoming Golombecks’ – Leibl and Binyomleh. It

was therefore called the Red Bet HaMedrash, and the ‘New-Old’

Bet HaMedrash, which was colored white, was called the White

Bet HaMedrash, until the town was destroyed. The synagogue

remained in burned ruins for nearly 13 years. At first, when the Red

Bet HaMedrash was not yet available, they would worship in

the burned out synagogue, between the walls, covered with a sort of

tarpaulin.

Rosa’s

building, where the first Bet HaMedrash in Zambrow was

housed, went into the hands of R’ Hirsch Michal Cohen. When the

synagogue was built, the Bet HaMedrash was liquidated. This

then became the location for R’ Chaim Nahum’s dry goods store. The

house was rented to the municipal chancellery, and in place of the

old Bet HaMedrash.... the municipal jail was put in place

[die Kozeh]. The building was last bought by Yisroeleh

Shia-[Be]zalel’s.20

Q. The Bath House and The Mikva

There is no

city that does not have a bath house and a mikva. There had

been a mikva in Zambrow for many long years. Without one, a

Jewish settlement cannot exist, however, a bath house requires

special permission from the authorities. It was difficult going with

the bath house: the authorities were not easily persuaded to permit

a bath house to be built – that is to say, a place to bathe in honor

of the Sabbath. From the perspective of the authorities, it had not

yet been demonstrated that this was necessary for the populace...

the Poles actually did not bathe. Up to the 19th century, only

special towns had concessions for a bath house. It was the Gabbai

Shmueleh Wilimowsky, who built the bath house in Zambrow. The Jewish

community invested about 1500 rubles in the building. It was built

on community land, near the Hekdesh. The bath house had its

own special brook, a cold and warm mikva, a sauna to steam

one’s self, and a cold room, after being switched with branches. The

bath house was leased for either a year, or three years, and the

community had a significant income from it. It was lit and heated on

Thursdays for the womenfolk, and on Fridays for the menfolk.

Occasionally, the baths would be kindled in the middle of the week,

and it was shouted out in the streets: ‘the bath is being heated!’

Friday, at midday, when the bath was thought to be sufficiently

heated (only men used the steam room) the stones in the oven would

glow, and Jozef the Shabbos-Goy had provided for enough

switching branches, the Shammes would go out into the street

intersections and announce: ‘To the baths!’ The military represented

a large clientele for the baths. Soldiers, officers would fill up

the baths, sometimes causing a scandal.. accordingly, for a while,

the bathing season was regulated: after candles were lit – the

soldiers can come and a gentile keeps watch and collects the

entrance fees.

They did not

always succeed in having a good bath house manager. The last of

these was R’ Alter Dworzec (Koltun) and it appears that the whole

history of the baths came to an end with him.

R. The Poswiatne

Together,

with the growth of the [number of] Jews in the city – the Christian

population also grew. They began to settle in the northeast side of

the outskirts of the town. Here, also, is where the post office was

set up, the court, and the religious Catholic institutions. And this

is the history of the gentile section at the outskirts:

Behind the

Rynek, on the way to Czyzew there was a large stretch of government

land, that was called Poswiatne. Shmueleh the Butcher bought this

land from the government for a song. Shmueleh the Butcher had an

‘in’ with the government, and was the contractor who supplied meat

to the military. Accordingly, he got this parcel for a cheap price.

A short time afterwards, the Zambrow parish decided to build a

large, stone Roman Catholic church, in place of the older wooden

building that stood at the entrance to the town, not far from the

Jewish cemetery. Since Shmueleh the Butcher sold off a parcel at a

cheap price for the construction of a church, Jews also bought

parcels and built new little houses along the church street, Ulica

Kosciolna, because this location had developed into a source of

livelihood: every Sunday, when the gentiles would gather from the

surrounding villages, to perform their religious rites – they

provide a great deal of earnings. The Jewish settlement grew and

branched out further in this manner.

S. The Military District

In the year

1882, Zambrow became a military [focal] point. The Russian

authorities decided to garrison two full infantry divisions and an

artillery brigade there. Smaller detachments of soldiers had been in

Zambrow for a while, before. Immediately after the Polish uprising (powstanie)

of 1863, soldiers were stationed in Zambrow. Seeing as there were

yet no barracks, they were dispersed throughout the town. At the

location where later there was a place for receiving guests, and the

old home of the Rabbi, and his small court house – was the post, and

at the place of the Red Bet HaMedrash – a mustering place for

the soldiers. The Jewish populace suffered some bit of morale

problems from the soldiers. They would constantly come around

begging for food, especially on the Sabbath – a piece of fish and a

piece of challah. Jewish daughters would be fearful of

answering the door at night. Jewish children learned the profanities

used by the soldiers. On the other side, they brought in income to

the town. Jewish tailors and shoemakers, bakers and storekeepers

that sold clothing, made a good living, and the population of Jews

in the town increased. It was only after deciding to station two

divisions of soldiers, that consideration was given to constructing

barracks. To this end, Captain Radkiewicz was sent to Zambrow from

the Warsaw Military District. He then purchased a large parcel of

land from Shmueleh the Butcher, on the road to Czyzew, on which to

erect the military compound: tens of barracks, places for drilling

and mustering, a Russian Orthodox chapel, housing for the officers,

warehouses and stables, an arsenal for ammunition, clothing, etc.

The contract to put up the entire military compound was taken by a

Jew from Lomza, named Manes Becker. He was an orphaned and solitary

young boy, and studied at the Talmud Torah in Lomza. Later on, he

apprenticed with a mason, and worked his way up a little at a time,

u8ntil he became a contractor for sizeable structures. Together with

his son-in-law Abramowicz (the son of the coppersmith of Lochow), he

built the first of the military barracks on Ulica Kosciolna, and the

street then took the name Koszaren. Many Jews, tradespeople,

merchants, contractors, all made a good living at the Koszaren.

Those Jews who were engaged in the construction, were called

koszarers’: Avreml Koszarer, Herschel Koszarer, etc.

Zambrow

became a large Jewish town, that provided sustenance to hundreds of

families, and people came to engage in employment from all

directions.

T. The Post Office

With the

growth of the town in line with the needs of the Jewish populace,

which made meaningful use of the post and telegraph services, the

small post office on Ulica Wola near the nobleman Sokoliewski, moved

over into the large premises, in Bollender’s house, on the ‘Uchastek.’

The post office was in Jewish hands, and was closed on the Sabbath.

Letters and other posted articles were conveyed by Jewish wagon

drivers, to the train station, and from the train station, in

accordance with an annual agreement with the postal authorities. The

first mailman was Jewish, ‘Alter the Mailman.’ His mother was a

midwife, and had relationships with the wives of the nobility and

the wives of appointed and employed people. It was because of her

connections that he became the mailman. The post office served the

entire Zambrow Gmina. However, it would not distribute to local

addresses in the villages. They would have to come to get their

mail...

No small

number of Poles fled the country after the Polish uprising.

Accordingly, their parents and relatives would come every Sunday to

Alter the Mailman, to inquire whether or not a letter had arrived.

Often, he would set out a small table on Sunday, not far from the

church, and respond to the interested parties. He was well

compensated for letters with produce from the villages and money. So

Alter became rich. His two-story wooden house on Ulica Ostrowska was

one of the nicest in the town.

In time, the

post office bought its own horse and wagon, and transported the

postal items to the train, as well as passengers. The post office

could no longer remain closed on the Sabbath because of the Jewish

mailman.

The post

office became secularized, and the meaning of ‘Jewish Mail’ was

again applied to letters that were not delivered in a timely

fashion, but languished somewhere in a pocket... Alter’s position

was taken over by a gentile from Goworowo.

U. The First Great Fire

As

previously mentioned, Zambrow survived a number of fires

concurrently. However, of special note, was a ‘Jewish fire’ that

broke out in the month of Tammuz (July) of 1895, that burned down

the entire Jewish settlement, the synagogue and the Bet HaMedrash.

From that time, Jewish Zambrow began to reckon time with reference

to this fire: [to wit]: ‘I was born a year after the fire.’

‘Such-and-such was before the fire,’ etc.

The first

great Zambrow fire – made [quite] an impression, and was written up

in HaMelitz and HaTzefira – the two Hebrew daily

newspapers of Russia-Poland. No Yiddish newspaper existed yet.21

Mr. Benjamin

Cogan writes in HaTzefira, Friday, the Parsha of Balak,

5655 (1895), that a large fire broke out. Approximately 400 houses

were consumed, and 100 stores, food shops and storage facilities,

two houses of study, and the synagogue. Only 20 houses remained, and

about 2000 people were left without a roof over their heads. When

the news reached Lomza, R’ Nachman Drozowsky organized an aid

initiative. The Rabbi, R’ Malkhiel, went on the Sabbath, with

balebatim from house to house to collect food, clothing and

money.

In

HaTzefira of 15 Av 5655 (1895) number 167, the committee thanks

Mr. Eliyahu Frumkin of Wysoka, on behalf of the victims of the fire,

for the bread and 100 rubles that he came up with. The committee

approaches the public with a request for assistance to the

unfortunate of the town after the fire. When Czyzew, Sedziwuje, and

Rutki had burned down – Zambrow did not rest, and it collected a lot

of money and clothing. Accordingly, it was now time to return that

help....

In

HaMelitz of November 19,1895 in 29/11. the Rabbi, R’ Dov

Regensburg thanks his friend, the editor, for the aid initiative

that he published in his newspaper, which on one occasion brought in

150 Rubles and another time, 50 Rubles.

In

HaTzefira, number 55 of 3 Nissan 5556 (1896), the correspondent

complains that since the Kozioner Rabbiner22 R’ Moshe David Gold moved

to Nowogród, municipal affairs have been neglected. The Chevra

Kadisha required 1000 Rubles a year for its needs, and no fence

has been put around the cemetery. Today, one finds bones there...the

money that was sent for those who were burned out, has been

distributed without an accounting, and those who stood closest to

the trough were the first to benefit from it...

In

HaTzefira Number 36, from the year 1897, Y. Gurfinkel writes

that the economic situation in the town has already improved, the

kosher canteen for the observant soldiers, who do not wish to eat unkosher food from the [regular] canteen, has re-opened, after two

years of dispute. Before this, a midday meal would cost a soldier

ten kopecks, and as a result there were few patrons. Now, a midday

meal is much cheaper, because the contributions from the supporters

has increased.

V. The Zambrow ‘Gangsters’

Every town

had its own pejorative nickname. For example there were the ‘Wise

Men’ of Chelm, and Warsaw Thieves. In the Zambrow area there were:

The gartl-wearers of Czyzew, The Bullies of Ostrow, The Kolno

package [carriers], the Jablonka Goats, the ‘Guys’ from Lomza, the

Jedwabne Crawlers, the Cymbal-players from Staewka, etc. Every town

knew how to describe its pedigree, and the story of its nickname.

Zambrow also

had such a nickname: The Zambrow Gangsters, meaning, bands of

thieves. This name was notorious in Poland. In a book, ‘By Us Jews’

which appeared in Warsaw in the year 1923, Mr. Lehman tells in his

article ‘Thieves and Robberies’ (page 56) why people from Zambrow

are called ‘gangsters:’ ‘In the 60-70 years (it really should be

70-80) of the previous century, there were gangs of horse thieves in

Zambrow. It is told that the horses were stolen deep inside Russia,

and at night, they were brought to Zambrow, and they were quartered

in the stables of the large Zambrow taverns. A couple of nights

later, the horses were taken out of their clandestine stalls, and

taken off to the Prussian border. The investigating judge, Tuminsky,

undertook to excise these gangs, and he succeeded. That is what is

written there, in the book.

Correspondence concerning the trial of the gangsters was printed in

the two Hebrew daily newspapers at the end of the prior century –

[in] HaMelitz in Odessa, and HaTzefira in Warsaw, and

we will introduce them here, in abbreviated form: A certain A. Z.

Golomb wrote the following in HaMelitz Number 123, on June 4,

1887: Approximately 90 men joined together, from the entire area,

even as far as Grodno, and carried out large scale thievery and

murders, assaults with intent to rob, and so forth. However, they

were especially notorious for the stealing of horses. The Chief of

the Secret Police in Lomza harassed these thieves, so they stole his

horse as well. When he became very upset and ashamed, the thieves

told him: he was to put 200 Rubles in a certain place, and they will

then return his horse to him. He placed the money in that spot – and

they took the 200 Rubles and didn’t return the horse as well. At

that time, he did a very daring thing: he traveled to Petersburg,

and went through a course on how to apprehend thieves. Upon his

return to Lomza, he had acquired the [added] title of

court-Investigator’ and had obtained all the rights to arrest the

gangsters. His attack against the gangs lasted for three years,

until he captured and arrested them all in Lomza. The trial took

place in May 1887 in the Lomza district court. Among the accused,

held in irons, were 33 Jews from Zambrow. The sentence was announced

on May 28: Of the men, 23 were found guilty, and 10 – innocent. One

of them, Moshe, was accused of informing on a gentile. Joseph L. and

Joseph Sh. robbed and raped a noblewoman. A boy, Mikhl L. stole a

goose and a few days later, attacked the owner and beat him, because

the goose was so scrawny. Among those arrested were a number of

prominent and respected balebatim from Zambrow, owners of

taverns, who were sentenced to several years of imprisonment. Two

prominent horse dealers from Zambrow Y. and N. were sent to Siberia

with their wives and children.

In the June

28, 1887 edition of HaTzefira Abcheh Rokowsky (see a separate

chapter about him later on) offered a rebuttal to the article by Mr.

Golomb, indicating that he was guilty of a sacrilege, because the

Russian and Polish dailies seized on it, and reprinted it. Mr.

Rokowsky argued that the court had added a variety of criminals to

the trial of the gangsters, because the police, in this manner,

wanted to raise its prestige. [He complained that] prominent

balebatim from Zambrow were arrested not because they were

partners in the gangs, but – because they were considered disloyal

citizens: they had not told the authorities that the gangsters were

stopping off in Zambrow on their way to the Prussian border. Abba

Rokowsky writes that Mr. Golomb created a tempest in a teapot

[literally: a storm in a glass of water] and insulted the Zambrow

Jews....

This matter

was discussed for many years in the shtetl. It was later

shown that a political issue was involved here: Germany was

interested in buying Russian dragoon horses. A gang of non-Jews,

Poles, carried this out. They would bribe soldiers who stood watch,

officers, etc., and they opened the military stables. Some of them

would then mount some of the horses, tie a row of other horses to

them, and go off n the dark night to the border. Zambrow was a

strategic point for them. It was possible to reach the border in one

night. Here, there were large stables that belonged to the three

brothers B. who owned taverns. From time to time, the gangsters

would lodge there, posing as horse merchants. The local Polish

community put pressure on the Zambrow Jews, the owners of the

taverns, to maintain silence. Also the Gabbaim of the

community, who were responsible for the deeds of their brethren, had

to keep quiet. For this reason they too, were arrested – but later

on they were released.

However, for

purposes of enhancing their prestige, the criminal police added

charges of ordinary theft and murder to the charges against the

gangsters, which had been ‘discovered’ and were, incidentally

recorded in reporting to the authorities. It was told: Horses were

stolen from a nobleman near Zambrow, night after night. the Chief of

Police said to the nobleman: leave two good-looking horses in the

stable tonight, and I will hide in the haystack, and will harass the

thieves. So that night, they not only stole these horses, they also

stole the jacket and sword of the secret agent...

For many

years, the family of horse traders that was sent to Siberia were

called – the Siberians,’ when they came back from Siberia. In town,

the truth was known, and the dignity of those who were mixed up in

this trial was not impaired.

So this is

the story of the Zambrow Gangsters, who marked out town with a less

than stellar reputation in the larger world.

W. The Second Great Fire

After the

[First Great] Fire, the town got itself back up on its feet. The

marketplace, and the surrounding side streets were quickly rebuilt.

Instead of single small houses, two-story houses were built. Several

tens of additional Jewish homes were added on Ulica Ostrowska, on

Ulica Bialostocka and Ulica Cieciorka. Commerce flourished, and the

houses of study – full of worshipers. Zambrow became the principal

city of all the surrounding settlements. Zambrow looked after the

Jewish settlement in Brzeznica, in Szumowo, etc.

Approximately 400 Jewish recruits were installed in Zambrow, and the

town had to provide for their kosher food., for their Sabbaths, and

Festival holidays, and other matters pertaining to their Jewish

faith. In general, it was the military that contributed most of the

income to the town. During the summer, the Jewish small businessmen

and tradespeople would be drawn to the ‘summer residence’ in

Goszerowo, where the Zambrow soldiers would spend the summer in

camp. Maneuvers would frequently be conducted – and at that time,

the town was packed with soldiers and the stored were full of them.

The town considered itself to be entirely Jewish, and was enclosed

in an Eruv,23 thereby permitting the town Jews to carry a

handkerchief, or a prayer book on the Sabbath, or to carry a

cholent, etc, until the Second Great Fire arrived, which broke

out on Saturday night, May 1, 1909.

About 500

Jewish houses were burned down. The misfortune was laid at the foot

of the Zambrow Christian Fire Fighters Command, which was

anti-Semitic in its sentiments. Once again, the town got back on its

feet quickly, and became much more beautiful and prosperous than

before. Ulica Kosciolna, with its sidewalks and pretty businesses,

became equivalent to what one would see in a large city.

From Bygone Zambrow

By Mendl Zibelman

(Miami, FL, USA)

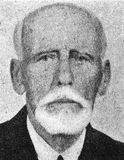

Mendl Zibelman

Introduction

How old was

Zambrow of yore? Who were its first Jews? How did they make their

living:

The

Pinkas of the Zambrow community was in our yard, from the first

day of its existence in 1828 until 1914, as well as the census books

of the same period, which were also in our possession, and

therefore, I can remember things that I would see, from

time-to-time, in the Pinkas. I also remember what it was that

I heard from elderly Jews of that time, and that which I am capable

of remembering on my own.

My name is

Mendl. a son of Israel-David the Shammes, of the former red

Bet HaMedrash in the Zambrow that used to be. My father was a

son-in-law to Moshe Shammes k”mz. These two people, my father and

his father-in-law, were the administrators of bygone Zambrow, for

approximately one hundred years.

A. Moshe Shammes, and My Father, Israel - David