Besides being good craftsmen and very talented skilled workers, the Jews made up the largest proportion of merchants in the large cities and small towns. Latvian companies in all industries were also highly developed by the Jews (Milman, R. Kaplan, the Hoff brothers, K. Misroch. R. Feldhuhn and others). The export and import of raw materials and finished products was in Jewish hands (Berman, Rosengarten, Schalit etc.) because of their good connections with the outside world. The Jewish bankers, for example the Lewstein brothers, Schmulian and Epstein (from Liepaja) were also well-known abroad. Large and small banks were founded with Jewish capital (the Nordic Bank and others). The founders of the Nordic Bank were Leiba Minsker, Ber Lewitas, Rabinowitz, Kirschbaum and others. Leading positions were held by Saul Hurwitz and Silitzki.

After Latvia became independent, it was the Jews who introduced it to the world and more or less got it off the ground. Latvia's good economic standing was created by the Jews alone. The Latvians themselves are an industrious farming people. For years they were subjugated by the German barons and had no talent for trade. Only a few Latvians became manufacturers, with the help of the Latvian government (1935), which endeavored to create a purely Latvian industrial sector. This effort, however, cost the Latvian government quite a bit of money. The country's currency was also created by the Jews (Friedman). The Jews played a large role in cultural life. It was Jewish professors who occupied the lecterns of the university and the polytechnic college. Moreover, there were many physicians who had an international reputation (Professor Wladimir Mintz, Dr. Idelsohn), musicians (Professor Metz etc.) and numerous other scholars and artists. Jews also played a huge role in the legal profession and the drafting of all the laws of Latvia. In this area they were supported by the Jewish lawyer Oskar Osipowitz Grusenberg of Petersburg. In Riga itself there were many extremely talented Jewish lawyers.

Jewish religious life was very vigorous. There were Jewish schools that gave instruction in Yiddish and Hebrew, as well as a few yeshivas and Talmud toras (Talmudic colleges and schools). In all the large cities and small towns of Latvia there were splendid synagogues and houses of prayer.

BesIdes the two goanim rabbis (Talmudic authorities) - the Rogazow rabbi (Josif Rozin) and Meir Simcha (Kahan), who both lived in Daugavpils and whom the reader will get to know in the chapter "The Jewish City of Dvinsk" - there were many other great rabbis. In Riga it was Mendel Zack, in Jelgava Owcinski, in Liepaja Polonski, in Zilupe and later in Friedrichstadt it was Paul, in T ukums it was the old rabbinic dynasty of Lichtenstein.

All of the names cited above are associated with the publication of various works of religious philosophy. Also well-known were the rabbis Kilow (Riga), Jemin (Vilani), Donchio (Ludza), Schub and Klatzkin (Kraslava), Placinski (Viski) and many others. Only a few of them died a natural death; all the others died as martyrs. Rabbi Kuk ZeI, who died in Palestine, was also born in Latvia.

Jewish religious life in Riga was strengthened thanks to the arrival of the world-renowned Lubavitcher rabbi (Schneiersohn). The deputy Dubin enabled him to come from Russia. In his Riga residence on Pulkveza Brieza Street one could meet many Hasidim (pious ones) from Latvia and the rest of the world. Shortly before the war he moved to America together with his whole family. His son-in-law Gurarie also followed him, and later on so did Chodakow.

Jewish liturgical singing was cultivated in all the towns of Latvia. The creator of music for the synagogue was Rozowski. World-famous singers graduated from his school (Hermann Jadlowker among others), and his compositions are known throughout the world. After his death, his position at the synagogue in Gogol Street in Riga was taken over by Hermann Jadlowker. Fortunately, he emigrated to Palestine before the outbreak of the war. Cantor Rabec (now in Africa) and Abramis were also very popular and well-known in Riga. Cantor Rabinowitz was active for a long time in the great choral synagogue of Daugavpils. Several important singers graduated from his school as well. After his death his place was taken by Friedland. Cantor Schloßberg was also born in Latvia (Ilukste) and thus bore the name of "Leibele lIIukster". Among the most significant conductors of Riga are the Jews Pisecki, Sklar and Abramis Jr.

In Daugavpils and Riga there were also well-equipped trade schools, whose graduates included leading professional craftsmen.

In Riga there was a splendid Jewish club with a permanent Jewish theater; there were also two other clubs, which bore the names of our great Jewish poets Bialik and Peretz. There were also numerous clubs in the provinces.

The Jewish university students had their own fraternities (Hasmonea, Vetulia). The Jewish polytechnic society was also very well-known in intellectual circles, and the Oze (health services) and OPE (education) organizations were active throughout Latvia.

There was a daily Jewish newspaper called "Frühmorgen" (Early Morning), edited by LatzkiBertoldi (Palestine) and Dr. Hellmann. One of its co-workers was the writer HerzMowschowitz. A monthly illustrated journal, "Jüdische Bilder" (Jewish Images), published by Jakob Brahms, had a large circle of readers not only in Latvia but in the Jewish world as a whole. The artist Michal Jo, among others, worked for it. The Russian press with all of its well-known newspapers such as "Segodnia" (Today) and "Segodnia Wietscherom" (This Evening) was actually in Jewish hands. The owners were Jakob Brahms and Dr. Boris Polak. The aforementioned newspapers had the Jewish co-workers Michael Milrud (Editor), Boris Oretschkin, Lecturer Weintraub, Professor Lasersohn, Anry Gry, the Machtus brothers, Lewin and others. All of them without exception wrote well. The owner, Jakob Brahms, was known for his excellent lead articles. The large modern printing house tor these newspapers, Rita, was also under Jewish ownership (Kopelowitz, now in Palestine).

The Zionist movement was especially well-received in Latvia.

The Nurock brothers, who were rabbis, and the lawyer Trohn were the veterans of the movement, and they participated in the first Zionist congress in Basel (Switzerland).

Later on, the revisionist Zionist movement (Betar) began in Riga in the person of Wolf Jabotinsky. He had founded his party on 17 December 1923 in Riga after his lecture at the Trade Union Club in Kenina Street. The other founding members were Aron Propes and the engineer Michelsohn. After a time they were joined by Dr. Jakob Hofmann, Benia Lubotzki and Moses Joelsohn.

A socialist Zionist movement (Poalei-Zion) also existed in Riga. The Jewish socialist party, Bund, also exerted a strong influence on Jewish working people. The Bund party was most strongly represented in Latgale.

The Mizrachi and Agudat Izrael parties had a decisive influence on the religious life of Jewish Latvia.

The Jewish Communists were also active, largely illegally until the introduction of the Soviet system. Thus many of them were incarcerated in the prisons of Riga and Daugavpils, and their names - Breger, Maitlis, Cipe, Rafael Schäftlin, Cenciper, Nochum Rappaport, Bubi Tuw, Isak Kohn and others - were very familiar there. After the establishment of Soviet power in Latvia, many Jews were appointed to responsible positions. For example, Dr. Joffe Jr. became the People's Vice-Commissar (Deputy Minister) of Health Services. The blind Professor Schatz-Anin also played an important role.

In the Latvian Saeima (Parliament) there were always Jewish representatives, such as Fischmann, the rabbis Morduchai and Aron Nurock, Morduchai Dubin, Professor Lasersohn, Dr. Meisel and Simon Wittenberg.

Rabbi Morduchai Nurock was even appointed once by President Cakste to form a Latvian government. Deputy Dubin also exerted a great deal of influence on governing circles (Dr. Ulmanis).

Until 15 May 1934 - that is, until Dr. Ulmanis seized state power - national cultural autonomy officially existed. The head of the Jewish division at the Ministry of Education was first Dr. Landau and later Chodakow. Morein had a position at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Samunow at the Slate bank.

In the beginning, the Jews in Latvia did not do badly. But in the final years (from 1934 on) various anti-Semitic currents arose, thanks to the proximity of Fascist Germany. These currents originated in the well-known Latvian Perkonkrusts (Swastika) organization. There were also various restrictions on Jews in trade and education.

After the Soviets set up their first bases in Ventspils and Liepaja in 1939, many wealthy Jews (Owsey Misroch, Felix Glück, Adolf Kaplan, Orelowitz, Kopylow, Bazalkin, Schmulian Jr., Elia Scher and others) sold their businesses within a year and emigrated abroad. In this way they saved their lives. Still others, such as Dr. Polak, Jakob Brahms, the industrialist Rafael Feldhuhn and others, who happened to be abroad at the time did not return to Latvia.

The establishment of Soviet power in Latvia then changed the situation of the Jews in general, The Jewish population of Riga increased to more than 50,000 as Jews moved in from the provinces. The larger merchants in the provinces did not wait for their businesses to be nationalized, but moved to the large cities before the Soviets could notice them. Likewise, the Jewish intelligentsia of the provinces, whose professional skills were no longer wanted, found work in the large cities. On 14 June 1941 the Soviets began a large-scale resettlement of the bourgeoisie to the Russian interior. This involved about 3,500 Jews in Riga and about 5,000 in Latvia as a whole, which amounted to 5% of the entire Jewish population. The list of resettled individuals reveals that many very wealthy people, for instance Misroch Sr. and Schmulian Sr., were able to stay, whereas small citizens such as craftsmen who were satisfied with the Soviets, or even people who were devoted to the Soviets and held responsible positions, were resettled. Only 1.25% of the entire Latvian population was affected. It is worth noting that the Latvians spread rumors to the effect that the resettlement lists had been drawn up by the Jews, which was absolutely untrue, since a far larger percentage of the Jews than of the Latvians was affected. The false accusations were only a pretext to retaliate against the Jewish population.

With the

introduction of the Soviet system in Latvia, the economic situation of

the Jews changed as well. For a short time the wealthy individuals

such as factory owners still had the possibility of transferring their

fortunes to foreign countries and selling their movable property. The

immovable property, however, was nationalized. The small and

medium-sized merchants were able to hold on to their businesses and

workshops until the outbreak of the war. During these years it was

possible for them to earn a great deal of money, but already people

were no longer interested in money in itself; instead, they invested

it

in valuables and other material assets.

During this period the Jews, like others, had more property than ever

before. Although the number of Jews in Latvia at that time was only

about 94,000 - that is, 5,500 fewer than before - the Jewish community

nonetheless entered World War II from a very strong economic position.

|

War (1941-1945):

The Germans March into Riga |

|

|

|

The Latvians fought on all fronts; they shot from the roofs and attics of their houses at the units of the Red Army that were in retreat. In the meantime, German planes could already be seen dropping bombs on the city's outskirts. On the radio we heard that Kovno (the capital of Lithuania) had been occupied by the Germans. The Lithuanian partisans were fighting just as the Latvians were. Every person one met had just one question: "What should we do?" There was no official evacuation, but a few trains were standing in the station. Understandably, they were stormed by a crowd of people, but for most of these people it was impossible to leave by train. Moreover, people said that the enemy was bombarding the trains, railroad stations and railway tracks, so it was impossible to get through. The city of Daugavpils, they said, was already occupied by the Germans and so only the stretch toward Valka-Pskow-Leningrad was open. Many Jews who got no seats in the trains came back from the railroad station. Others halted trucks and begged the drivers to take them along. On the way, many drivers demolished their vehicles on purpose and then disappeared. A large portion of the civilian population was also taken along by the retreating Red Army. Women with their children sat on the tanks that were rolling away. Some of the Jewish young people who had worked for the Soviets decided to leave on foot. Many of them were stopped on the road by the Latvians and then handed over to the Germans; others died during this march. There were also many Jews who did not want to part from their possessions, which they had worked so hard to acquire. Though the reasons for staying were extremely varied, there was one thing nobody could imagine: that the destruction by the Germans and by the local population would be so merciless. We knew, of course, that we could expect no good from the enemy. As for me, escape was entirely out of the question. At the time, my son was in the hospital with a broken foot and I had to bring him home from there, since everything was falling apart. Because he was confined to bed, we had to stay in any case. Only a few Jews came to Riga from the provinces of Kurzeme and Zemgale, which the enemy was already starting to occupy. By this time the number of Jews in Riga had already decreased by 10,000 through the evacuation. Thus when the German army marched in, there were still more than 40,000 Jews in Riga. On the night of 29 June 1941, strong pressure from the Germans could already be felt in the city. The Red Army withdrew in a totally disorganized way toward the province of Vidzerne. The soldiers were tired, hungry and thirsty. We put out pails of water on the street for them, we collected food from the neighbors and threw bread to them. But this was only a drop in the bucket! In the meantime, the Germans were bombarding the city. The bombs were dropped near the old city center, where the bridges were. But the bridges had already been blown up in the previous few days by the retreating Russians. St. Peter's church, known to us all, which had the highest steeple in the city topped by a rooster, burned down. It was not set aflame by the Soviets, as Latvian propaganda would have it (even photos of this fictional deed were distributed); it has now been determined that it was destroyed by the German military forces. The day of transition, 30 June, was very quiet. All one could see was individual Red Army soldiers who had been left behind. There were no people on the streets, only tanks on various street corners, whose task was to cover the Red Army's retreat. In the meantime, the Latvians prepared to greet the enemy. The red-and-white Latvian flag was brought out of storage; people also had flags bearing the swastika ready. The Perkonkrusts organization was already working out the plans for our destruction, having no doubt that the enemy would approve of them.

On 1 July the German army forced its way

into the city. The Latvians greeted the enemy with flowers, wearing

their Sunday best. All the houses were decorated and ornamented with

flags, The radio broadcast the old Latvian national hymn, "Dievs

Sveti Latviju" (God Bless Latvia), and also the Horst Wessel song.

All of this made a very strong impression on the Latvians, and they

were convinced that now a new era of independence would begin. But all

this was only a well-prepared prelude on the part of the Germans.

Power was never officially handed over to the Latvians; moreover, the

playing of the Latvian hymn was never again permitted. On the same

day, 1 July 1941, the Latvians announced on the radio that all

nationalistic Latvians should register immediately for the struggle

against the internal enemy (the Jews). The gathering point for this

action was the headquarters of the Aizsargi (Guards). This was the

home of the professional associations. There, weapons and

red-and-white armbands were distributed to everyone who registered,

without exception. Every group was assigned a district that it was

supposed to "deal with". The call to nationalistic Latvians is

associated with the name of the Latvian Captain Weiß.

After the German occupation of Riga, Jewish life came to a virtual standstill. On the first day, no Jews went out onto the streets, and there were no incidents. In the early morning of 2 July I received a phone call to tell me that one of my brothers and his son-in-law had been arrested. I immediately got in touch with my friends and closer acquaintances and found out that the Latvians had begun to arrest Jewish men in the city. They were going from house to house and dragging out my fellow Jews. These were brought in groups to the police headquarters, police stations and prisons. The captors were Latvian youths in civilian clothing armed with weapons and wearing red-and-white armbands. Of course there was no lack of beatings and looting. Many people were even shot dead in their homes (e.g. Gogolstraße 7). That same morning the telephones belonging to Jews were cut off. It was dangerous to go out into the street, but people did not feel safe at home either. All the Jewish tenants of our building gathered together in the apartment of our neighbor Dr. Magalif to discuss the situation. We could think of no way out and were forced to accept our fate. The next day it was my turn. Armed Latvian youths forced their way into my apartment. They plundered whatever they could find, and took me and my son, who was still sick, away with them, along with the other Jewish tenants of the building. Then they led us all together to the police headquarters, or prefecture. On the way we were joined by more and more Latvians who walked alongside us and beat us mercilessly. They shouted, "Jews. Bolsheviks!" and jeered, "Stalin's unconquered army is in retreat!" As we passed the monument to the great Latvian poet Blaumanis. I saw my friend the lawyer Dr. Singel. He had been so badly beaten that he was covered with blood. He was accompanied by heavily armed guards. He signaled to me with his hand, as if to say, "My fate is sealed." And indeed he was murdered the same day.

Trucks stood ready at the canal near the

prefecture to take us to the prisons. As we walked into the courtyard

of the prefecture, it became clear to me that a catastrophe was

breaking in on us.

The large prefecture building was full of Jews. Screams were heard from every direction, so horribly were the Latvian murderers tormenting their victims. Their sadism knew no bounds. Old and sick people were brought into the courtyard without underwear, totally naked. People who had formerly played an important role in society now stood there beaten and bleeding. They were dragged around by their beards. Young women who had been brought in were stripped naked in the courtyard and thrown into the cellar rooms of the prefecture to be used for orgies. Venerable old Riga Jews were dragged here, doused with water, and beaten; their captors jeered at them the while. Moreover, they sought out Jews with especially full beards and forced them to polish the Latvians' shoes with them. This was so-called Latvian culture! So far, no uniformed German had yet appeared in the police headquarters. I stood in the courtyard all night with my son and my neighbor Osia Pukin, since there was no room in the prefecture itself. We did try to go upstairs, but it was impossible. This was lucky for us, because only this saved us from certain death. All of those who were upstairs ended up in prison and were shot. Many friends and acquaintances passed by me; among others. I saw my good friend Preiss. The next morning we were taken out of the courtyard to work. My son and I had to fill up the trenches opposite the Polytechnic College. On the way there, we were beaten again. It was unusually hot and we were tormented by thirst, but of course we didn't dare ask for something to drink.

Thus we were chased until late

evening from one task to another. Once again we spent the night under

the open sky in the prefecture courtyard. The next day we had to load

tires from a large warehouse onto trucks. The well-known Riga jeweler

Widzer worked with us. He was moaning and weeping because he had lost

his son. After we had finished loading the tires we returned to a

large room in the prefecture in which there was a piano. The Latvians,

who clearly were sadists, held truncheons in their hands and made us

do drills; for instance, they forced us to sing and play the piano.

They ordered some of the Jewish singers to sing Nazi songs that they

didn't know. Finally they forced all of us to sing the

"Internationale". None or us knew why we were being

forced to sing this particular song. They explained to us,

once

again with their truncheons, that this

would be the last time we sang it. I felt my strength leaving me and

feared I would be unable to stand the further tortures

of

the Latvian murderers.

My greatest

sympathy was for my young son, but of course I was unable to help him.

Fortunately, at this moment my neighbor Pukin appeared, accompanied by

a German soldier. The soldier requested that my son and I be released

so that we could work as decorators at the field commander's

headquarters.

We now left the house of martyrdom with relief and went to the command headquarters across the street from the City Opera. I was recommended to Spieß (Sergeant Major) Lockenfitz as a capable craftsman. He was convinced of my ability and gave me various instructions. We also received a pass that protected us from the Latvian henchmen. My wife's joy at our return was of course indescribable. She told us many things she had heard in the city during our absence. She had not reckoned on us returning at all. She herself could still move about unharmed, as she looked very Aryan. Many of her stories seemed totally unbelievable, but unfortunately all of them were later confirmed. From my balcony I saw the burning of the great synagogue on Gogol Street and of the OldNew synagogue and the Hasidic houses of prayer in the Moscow suburb. The synagogue on Stabu Street was not destroyed until later. The flames claimed victims everywhere, because Jews were driven into them to die. Thirty Jews and Rabbi Kilow were killed in the synagogue on Stabu Street. The holy torahs (holy scrolls) were dragged out of all these synagogues, defiled and burned. Many Jews, dressed in their prayer shawls and talith, flung themselves into the flames to save the torahs. All of them were killed.

The only synagogue the murderers left

standing in Riga was the large, well-known Peitavas synagogue in the

old town center. It was spared only because it stood in the midst of

apartment buildings. But its interior was demolished like the others.

In the meantime, the Latvians had moved the staff of Perkonkrusts (Swastika) to the house or the banker Schmulian on Valdemara Street. We knew that this murderers' den was the home of notorious Perkonkrusts members such as Arajs, Cukurs, Teidemann, Razum and Freimanis. Moreover, they attracted a considerable portion of the Latvian intelligentsia from the student fraternities to their side. Many of these people, who have hundreds and thousands of murders on their conscience, are living today out in the world in total freedom. They have simply made use of the right to asylum that is guaranteed by the great democracies. At that time, Riga alone did not satisfy their bloodlust, so they organized gangs - here too with the help of the Latvian intelligentsia. These gangs moved from city to city, from town to town, in order to kill the Jewish population there in the most bestial way.

The cellar rooms of the former home of the

banker Schmulian were quickly transformed into prison cells. Now

countless Jewish women and men were brought there either to be shot

immediately or transferred from there to regular prisons.

I myself had to work, together with my son and my friend Pukin, in the field headquarters. Every morning we went to work together, carrying our pass, which protected us from the Latvians. One time, as we were walking through the beautiful Wöhrmann Park in Riga, the Latvians drove us out of it. Nor can I forget how once during the first few days, as we rode in a streetcar, the woman conductor could not get over her outrage. She was beside herself with fury over the fact that a Jew would dare to do "something like this" at all. She immediately rang the bell to stop the streetcar and we were literally thrown out. In addition to my work as a decorator, I was also used at the headquarters as a cleaner, furnacestoker, and sweeper of the sergeant major's room and office. This sergeant major, who was regarded as the master of the house, was a very decent and sympathetic person. During the time I spent there, a large work crew of Jews was occupied mainly with bringing wood into the cellar and managing the transport and storage of the furniture stolen from Jewish homes. A Latvian artist named Pudelis pointed out to the commandership the Jewish homes that were most worth looting. My home also fell victim to these thieves. During my absence the Germans went to my home together with Pudelis, stole all the objects of value, and had them brought to the headquarters. They were immediately used to furnish the private rooms and office of General Bambergs. For nearly two years I now had to clean my own Persian carpets, but what was I to do?

In the field headquarters, we soon got to

know the gendarmerie administration, which in those days protected us

from the Latvians in emergencies. Later on, the Jewish workers at

the headquarters received certificates

stating that it was not permitted to use them for other work or to

confiscate any further items from their homes. Nonetheless, one day

the Latvians dared to go to a house in Mateja Street to arrest and

imprison eighteen people who worked with us. This incident was

reported to the sergeant major. Moreover, the Latvians had destroyed

the work passes that he had signed and stamped with the field

commandership's official stamp. He flew into a rage and decided to

free "his Jews" immediately. To this end, he and some of his

soldiers drove, heavily armed, to the prison. He had with him a list

of the imprisoned Jews and ordered the Latvians to release them at once. All

of them were released except for a barber. "Where's my face-polisher?"

the sergeant major called out, and he did not relent until the barber

was brought in too. On this occasion he noticed an old Jew. "That's

my rabbi," the sergeant major now said, and thus freed twenty-five

instead of eighteen persons. Unfortunately, such people were not left

in their positions for long; they were replaced with others who had

different views.

In the meantime, in the city the Jews' situation had worsened. Both the Gestapo and the Wehrmacht (army) were continually confiscating more and more furniture in order to furnish their own quarters. Without deliberation or planning, they took what they needed from Jewish homes. During these actions, people were often simply brought out and murdered on the street. This happened, for example, on the other side of tile Daugava to the lawyer Heidemann, the leather manufacturer Rosenthal, and a number of others. They were shot most cruelly on Uzvaras Laukums (Victory Square).(1) Because the Germans were still busy with their military affairs, power was still in the Latvians' hands. Nobody whatsoever thought of feeding the Jews. They were pulled out of the lines standing in front of the food stores if they were recognized as such. The atrocities against them were unending. For example, one day a vehicle full of armed Latvian volunteers drove to 9 Kalnu Street in the Moscow suburb. All of the building's Jewish tenants were forced to leave it immediately and taken to the old Jewish cemetery. Here they were locked into the synagogue and burned alive in it. Similar actions were also carried out in the new cemetery. The Jews who worked there were rounded up together with Cantor Minz, who was well-known in Riga, and his family, locked into the prayer house and burned alive. The bones of these martyrs have now been found and given a solemn burial.

The only Jews who were treated somewhat

better by the Latvians and were not arrested in the initial phase were

the members of the Jewish Latvian Freedom Fighters association. But

that did not last long either.

In the context of these notes I must relate the following experience. In mid-July 1941 I passed the house at 52 Krisjana Barona Street on my way back from work. /\ group of prisoners from the Red Army was being led past it. They were barefoot, ragged and starving. Latvians wearing red-and-white armbands were escorting them. At their head marched a young German wearing an armband with the swastika, At this moment, a poor Jewish woman holding her child by the hand came by. She was carrying a loaf of white bread, and out of sympathy she made the child give it to a Russian. When the German saw this, he shot the Jewish woman, the little girl and the Russian on the spot. The Latvians cheered! At the same time I remember another incident that happened five years later. In mid-July 1946, on the same street in front of the same house, we were passed by a group of German prisoners. Someone threw a full bottle from a top-floor window, and it fell on a prisoner and killed him immediately. Thus the innocent blood that had been shed before was now avenged!

The following experience also belongs

here. At that time a Jewish woman worked at the field headquarters

together with me and the others. Her name was Ellis and she had been

born in Hungary, She was a professional chanson singer and piano

player at the well-known Riga night club Alhambra. Now she worked as a

cleaning woman at the headquarters, mainly in the rooms of the

commander, Captain Fuhrmann. He noticed her and decided to save her.

He had Aryan identity papers issued for her. Later on, when the

situation grew dangerous, he sent Mrs. Ellis to Vienna with a letter

of recommendation that got her a job as a singer on the radio. By

chance, the all-powerful Minister of Propaganda Goebbels heard her on

the radio in Berlin. He realized that when she sang in the style of Zarah Leander, she performed the songs better than the famous Swedish Zarah herself. With great delight, he now told the people around him

that he had found a "genuine" German Zarah and would soon make it possible to listen to her in Berlin. The new "German" star was now

invited to come to Berlin. She was asked to report directly to the

great Goebbels, who would organize a concert for her with a

select government audience, The director

of Radio Vienna was in despair, for he knew all about this star who

was not quite "kosher". What to do? It was decided that "Zurah" would

be declared ill. Thus the "German" Zarah was saved, and today she is

walking around freely in Vienna with Jewish identity papers.

The Latvians' cruelties worsened from day to day. They would simply round up Jews on the street and force them to do all kinds of work; they not only beat them mercilessly but murdered many of them. For example, one group often Jews who were repairing a damaged bridge over the Daugava in an Organisation Todt (OT) work group were simply thrown into the water, where they drowned. The looting of Jewish homes became more and more frequent. The owners were not only robbed, but many of them were killed on the spot. The Latvian murderers even went as far as to simply hack off the fingers of living people merely to gain possession of their rings. If apartments were needed, the Jewish tenants were thrown out on the spot without being allowed to take a single thing with them. There were two methods: either the people were arrested and taken to the murderers' headquarters at the Perkonkrusts center, or they were put into prison. Nobody returned alive from either of these places. One day Lecturer Weintraub came to me in despair. He had had bad luck: after making a lecture tour in America he had returned at the worst possible time. Now his apartment too had been taken away from him, and he stayed with me for a few days. Shortly after that he tried to commit suicide, but was saved. On his second attempt he succeeded. Many Jews were driven by their desperate situation to commit suicide. The Friedmann family killed themselves by gas poisoning (both husband and wife were doctors).(2) The Well-known jeweler and circus entrepreneur Tabatschnik and the shoe dealer Fraenkel also died horrible deaths. Terrible news came from the prisons (see the chapter on the Central and Terminal Prison). There was no longer any medical help for Jews. All of them were thrown out of the city hospitals. Even the Bikur Cholim Jewish hospital (Milman Foundation) on Maskavas Street was cleared out by force. Later on, an SS field hospital was set up there.

The press was full of inflammatory

articles against the Jews, and leaflets illustrated with the most

fantastic pictures were distributed (see the chapter 'The Press in

Riga During the German Occupation").

At the end of July the Riga field commandership was changed into a city commandership. All authority for civilian affairs was also set up. Its director was Nachtigall, a Reich German. He was the one who signed the first regulations concerning the Jews. Regulation One banned them from public places. Jews were no longer permitted to use city facilities, parks and swimming pools. The second regulation required Jews to wear a patch in the form of a yellow star (mogen David). It had to be about 10 centimeters wide and be sewn onto one's clothing on the left side of the chest. Violations of this regulation were punishable by death. But the Jews of Riga wore their stars with pride!

Another regulation decreed that the Jews

should receive 50% less food that the Aryans; and they could obtain

even these reduced rations only at the risk of their lives.

Buoyed up by their victories on all fronts, the Germans decided to gradually take over civilian rule entirely and thus organize everything according to their own pattern. Calm and composed in their typically German way, they began to do so in August 1941, The Latvian language was recognized as the country's second official language. In order to cope with these extensive organizational tasks, they summoned the Baltic Germans to help them. The latter had previously been called on by Hitler to leave the Baltic countries. These anti-Semites were now the ringleaders of every measure. The Baltic German Altmeyer took over the city government. He signed every order to confiscate apartments and so on. In mid-August all the Jews in Riga were registered. This took place at two locations in the city center and one in the Moscow suburb. I had to register, together with my family, in Cesis Street. There, all the Jews were badly beaten by the Latvians. This registration was carried out in order to determine how many Jews were still living in Riga after the many murders in the city and the executions in the prisons (see the chapter on the Central and Terminal Prisons). In the meantime, further regulations were decreed:

1) The Jews had to wear a second yellow

star (mogen

David) in the middle of their backs.

One could now see the Jews walking to work, one behind the other and marked with two yellow stars, in the gutters of tile streets of Riga next to the sidewalks. Of course there were alI kinds of accidents due to cars and the like.

At first we were very downcast by this

treatment, but we soon grew accustomed to it, as

well

as to the jeers of the local people.

The Gestapo arrived during the first few days after the Germans' entry into Riga. Officially it took over all the prisons on 11 July J 941, but on this date the prisons already contained a significantly reduced number of Jews. The Latvians had made sure or that! A Jewish work group was forced to remove the furniture from Jewish homes. The first confiscation took place in the large house of the Nesterows in Andrejs Pumpurs Street. After that, not only all the Jewish homes but also all the Jewish shops on Ausekla Street in the Vorburg district were occupied. The Gestapo offices were set up in the former Ministry of Agriculture building on Raina Boulevard. Not only Germans but also Latvians and Russians were employed there. A special division with an examining magistrate was created for Jewish affairs, and the well-known Gestapo methods were introduced. All too soon, the cellar of this building became well-known to us Jews. Anyone who entered it could reckon with his death; at the very least, people were sent from there to prison, which also meant the end - that is to say, death by starvation. A large black flag hung next to the swastika flag on top of the beautiful city administration building across the street. The Gestapo administrative offices were located there. Later on, the Gestapo headquarters for all of Latvia were set up in a former museum building at the corner of Kalpaka Boulevard and Alexander Boulevard. It was full of the loyal pupils of the monstrous criminal Himmler. Their names were: Dr. Lange, Krause, Mügge, Kaufmann, Roschmann, Deiberg. Nickel, Jenner and many, many others. All of them shared the blame for the mass murders of the Jews. The reader will hear more about them later. The Police General of Ostland, General Jeckeln (reportedly Himmler's brother-in-law), had his residence in the former Saeima (Parliament) building on Jekaba Street, formerly know as the Knights' Hall. Now Jews died horrible deaths in this palace of "chivalry" too. On 5 February 1946 after the liberation, when General Jeckeln and six other generals were hanged by the Soviets on Uzvaras Laukums (Victory Square), we surviving Jews felt tremendous joy. The trial of Jeckeln was held in the building of the former Latvian Association, now known as the DOKA (House of the Red Army), in Merkela Street. In response to State Prosecutor Zawialow's questions he replied: "The number of Jews brought to Latvia from abroad is just as unknown to me as is the number of Jews killed in Latvia. Even before we Germans assumed power, so many Jews had been exterminated by the Latvians that a precise number could no longer be determined." When he was asked, "Why were Jews brought to Latvia from abroad to be exterminated'?", he answered: "Latvia was the appropriate venue for these murders."

We survivors are only too familiar with

the "appropriate venue" which the Latvians created at that time!

A special Bureau of Jewish Affairs was also set up in the prefecture. The business at hand was the introduction of the Nuremberg Laws, which dealt with the issue of mixed marriages and the children produced by them. Men and women in mixed marriages were forced to divorce their spouses. If Aryan husbands refused to divorce their wives, the wives were sterilized. This murderous operation was performed on many Jewish women. All of these prefectural matters were in the hands of the Latvian Captain Stieglitz. Besides the prefecture, a Field Commissioner's Department was established. It was headed by Field Commissioner Drechsler. On the first anniversary of the conquest of Riga he delivered a great eulogy to the "loyal Latvians" in the State Opera House. All of the later regulations against the Jews were connected with Drechsler. After a special ministry had been founded for the eastern territories (Ostland) by the notorious Jew-killer Rosenberg, the equally virulent anti-Semite Lohse was appointed Commissioner of Ostland. As a reward for their loyalty and devotion to the Hitler regime, the Latvians were granted their own administration. A small puppet government headed by the Latvian General Danker was created. In my opinion Danker, who was half-German, felt more sympathy for the Germans than for the Latvians. The directors - that is, ministers - in his government were well-known Latvian public figures. The former Latvian President Kviesis, now deceased, occupied an important position, as did the well-known Valdmanis. The former was Director of Justice, the latter Attorney General.

These "loyal servants" not only

contributed a very great deal to the great Jewish catastrophe, but

also poured oil on the fire whenever they could so as to make our

situation eyen more difficult. This is how the so-called "liberal

Latvian intelligentsia" behaved during that period.

The situation of the Jews worsened from day to day. There was no longer anyone who could defend our cause. All of the socially important Jewish public figures of Riga either had been murdered or were in prison. At this time my comrade A. Pukin and I were friends with the lawyer Eljaschow. At that time, many members of the Jewish Latvian Freedom Fighters' Association were still at liberty, because some of the Latvians still respected this organization. But when it came to looting, even they were not spared. Every day when I visited the lawyer Eljaschow I saw that another piece of his furniture was missing, taken away by the Latvians since my last visit. My comrade Pukin and I persuaded Eljaschow - by taking full responsibility for his decision to head the Jewish community of Riga. His wife, who was also a lawyer and very intelligent and clever, reinforced our efforts. We based our request on the fact that he, as Chairman of the Jewish Latvian Freedom Fighters' Association and a well-known public figure, would have a certain amount of influence on the Latvians. He accepted our suggestion and also persuaded the no less capable Blumenau (the older of the Blumenau brothers) and the universally respected Grischa Minsker to work with him. Both of them had also played a large role in the ' Freedom Fighters' Association. Now these three men made a genuine effort to improve the Jews' situation, using all their possibilities - but unfortunately without any success. They were not officially recognized by the Latvian administration, and they had no access to the German authorities. I myself once tried to arrange an audience for them with Fuhrmann, who was the commander at that time, at the German Field Headquarters, where I was working. And Fuhrmann promised me to grant them an audience. When they arrived I had to lead them through the back door of the courtyard, but even so they were not received. Fuhrmann explained to me that he could not risk it.

In the meantime, a regulation was passed

regarding the creation of a ghetto. An official representative body

for Jewish affairs was appointed and recognized. The three

aforementioned persons (Eljaschow, Blumenau and Minsker) were now

joined by Kaufer (of the Zasulauks Manufacturing Co.) and Dr.

Blumenfeld, and later on by a Vienna Jew named Schlitter, who had

easier access to the Germans. These men wore wide blue-and-white

armbands with a large Star of David on their left arms. These insignia

gave them the right, among other things, to use the sidewalks and the

streetcars.

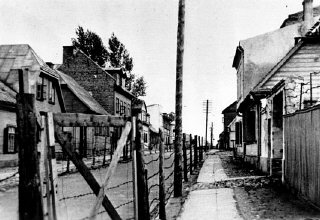

According to the regulation, "a ghetto in which all Jews have to be quartered must be established in Riga by 25 October 1941". The site of this ghetto included the left side of Maskavas (Moscow) Street, going from Lacplesa Street to Jersikas Street and ending with Zidu (Jews') Street next to the old Jewish cemetery. From there, the boundary extended along Lauvas Street to Liela Kalnu Street; then from the right side of Liela Kalnu Street along Daugavpils, Jekabpils, Katolu, Sadovnikova and Lacplesa Streets back to Liela Maskavas Street. The creation of the ghetto now moved the Jewish center to the Moscow suburb, A large schoolhouse at 143 Lacplesa Street was assigned to the Jewish Committee. In the garden and the courtyard of this house one could meet an endless procession of Jews who had been thrown out of their homes, together with their last remaining belongings. The pharmacist Katzin (owner of the Golden Series) greatly helped these unfortunate people. Many Jews also came to find out about the regulations concerning them and to hear news from the city center. The Jewish Committee created various authorities, including a Billeting Department, which was headed by Mrs. Blumenfeld (Peka). The Legal Department was headed by the lawyer Finkelstein, and economic affairs were the responsibility of Robert Schlomowitsch and many others. The surviving Jewish intelligentsia and all the significant Jewish public figures now tried as actively as they could to alleviate the great misery of their co-religionists. To enable the Jews to receive at least the 50% food ration allotted to them, shops were set up especially for them in the Moscow suburb. The first shop was opened in Sadovnikova Street under the direction of Levius (who had previously owned a clothing shop). Later the number of these shops increased significantly. The fact that now all Jews were forced to shop in the Moscow suburb eliminated the danger that they might have to stand in lines together with Aryans. Food was handed out in exchange for special food stamps that were checked off in a food distribution register. The food stamps and the book were yellow and bore the title "Zids" and "Jude" (Jew) in large letters. Of course everybody stood in long lines in front of the shops, and thus the question arose of whether the Jews had the statutory right to stand on the sidewalk. It was decided that the Jews had to stand in the gutter next to the sidewalk!

In the meantime, a barbed-wire fence was

erected in great haste around the new ghetto. Because one fence was

deemed insufficient, a second one was erected as well. The first

fenceposts were driven into the ground at the corner of Maskavas and

Lacplesa Streets, and from here the work proceeded rapidly. A few

large buildings were left out of the fenced-in area, contrary to the

law regarding the ghetto. This was a disadvantage for us. For example,

on Katolu Street a large comer building was excluded because it housed

the Svetlanov brothers' knitwear factory. A carpentry shop at 22 Maza

Kalnu Street, just inside the ghetto, was excluded: so were a small

chemical factory in Ludzas Street near Lauvas Street and a lumberyard

on Jersikas Street. A small wood-processing factory belonging to

Aryans on Blech Square, which was so bloody for us, was also excluded

from the ghetto. The Aryans who worked there now received special

passes that gave them access to the ghetto. All of these factories

were once again closed off from the ghetto on all sides with

additional barbed wire so that the Aryans could have no contact with

us whatsoever. Later the house on Maza Kalnu Street was handed over to

the Jews and included in the Large Ghetto.

In a space where previously a few thousand people had lived, tens of thousands of people were now forced to exist. This neighborhood had been inhabited mostly by Russian workers who were adherents of the old Orthodox Church (Staroobriadcy). It had traditionally been regarded as the Russian center. Now, even though because of the ghetto the Russian inhabitants were offered better and more comfortable apartments in the citym they did not want to part from their neighborhood. For them it was a tradition to have their splendid Orthodox churches near their homes. The housing issue in the ghetto was one of the most difficult problems to solve. At first, six square meters were allowed per person; later, this space was reduced to four square meters. Every inch of space was utilized. Great struggles were fought in order to get an apartment. Both the Wehrmacht and the Gestapo had requisitioned the best houses for the Jews who worked for them. The Jews exploited their connections with the units they had worked for, and thus received better apartments. The Jewish Committee member Minsker finally put an end to this preferential treatment by forbidding people to come to the Billeting Department together with Aryans, including even high-ranking military officers, in connection with housing affairs. My colleague Snejer and I received two small rooms for ourselves and our families in the large building at 2 Maza Kalnu Street. My comrade's father-in-law Borkon, a lawyer from Daugavpils, also lived with us. The days until our move to the ghetto were already counted, and gradually people began to prepare for the move. One must imagine this move to be roughly similar to the Jews' exodus from Egypt (Isaiah - Mizrahim). Everything happened bchipozoin (in haste). We were not allowed to take along large pieces of furniture, only at most our beds, small cupboards and the like. Now people packed only the essentials, and everything else was left behind. Some people sold their things for practically nothing, and still others were paid nothing whatsoever for them. The Latvians allowed nothing at all to be taken out of certain houses. The streets leading to the ghetto were jammed with small wagons carrying household goods. The Russian population moved in one direction toward the city center, the Jews in the opposite direction into the ghetto. Not only did the professional movers demand high prices from us, they also look things away from us. In some cases they even took off with all of our belongings. But whom could we complain to? Nobody was responsible for prosecuting such incidents. To "relieve" us further, the Latvians posted guards on Daugavpils Street and other streets: they took away everything they could from us and beat us mercilessly besides. All of our weeping and screaming did not help us. The hours were numbered and the ghetto had to be locked up.

On Saturday, 25 October 1941 we were locked off from the whole world. We were completely surrounded by enemies and felt as though we were in the lion's jaws. But we Jews had already experienced so many difficult times and great losses in our history. and had emerged as the victors again and again. So we thought to ourselves on this 25 October as well: be the sacrifices ever so great, we'll come through, no matter what! Today I sit in Germany. which we cursed so bitterly, and record the churbn of our people. But in my spirit I already see a new, healthy generation that has been tried in battle! We have lost millions of people, but in the course of time we will perhaps replace them after all. At this point I want to remind my readers of the words of one of our martyrs who bravely called out to the enemy as he faced certain death - the rifles had already been aimed at him: "Don't think the Jewish people will be destroyed with my death; the Jewish people lives and will live forever!" (Herbert Machtus) Our martyrs went to their death singing the Jewish hymn, the "Hatikva".

Od jisroel chaj!

(The

Jewish people lives!) II. As soon as the ghetto was locked, the following decree was issued: "Anyone who goes too close to the barbed wire will be shot without previous warning." On the very first night there were two victims on Jersikas Street. They were women, and when they were shot they fell directly onto the barbed wire, since the fence was so close to the narrow sidewalk that one practically had to touch it. After this incident the Committee immediately passed a regulation on travel inside the ghetto. Gaps were made in the fences of all the courtyards so that people could pass through them everywhere. At night our guards would disturb us with a lot of unnecessary shooting. The Latvian guards wore Latvian military uniforms, and at first they even had the old Latvian insignia on their caps. They wore green armbands, and for this reason we called them bendeldicke (armband wearers). The guards occupied a small yellow wooden house at the ghetto gate, and from the courtyard of this house they had access to the Jewish Committee. The Latvian guards were reinforced by a few German Wachtmeister (police patrolmen) from Danzig. These were the real leaders and gave the orders. In the first few days, the returning work crews entered the ghetto directly through the ghetto gate. Later, so as to monitor us more closely, they made us first go through the guardhouse courtyard. Here we were searched very thoroughly and beaten very cruelly. Many of us wiII never forget this narrow entrance to the courtyard. There too we had victims to mourn. After only two days, on 27 October, a Czech Jew was brought from the prefecture, shot immediately in the guardhouse courtyard and buried there. The poor man had gone to the prefecture to find out his future fate, and had been sent directly to the ghetto.

The Committee worked very intensely and meetings were held continually, since there was a great deal to do. There was no housing for the Jews who had come from the city at the last minute. Some of them even had to be housed in the Committee's rooms. Inspectors (Friedmann etc.) were appointed to monitor housing affairs. A home for the older people was set up on Ludzas Street, and a second one was set up next to Blech Square. Professor S. Dubnow had also been assigned a room on Ludzas Street. The Labor Authority was headed by representatives of the Field Commander's office, the Aryans Stanke and Dralle. It too was working at full capacity. The intermediary was the Jew Goldberg from Rujene; he had taken on a very difficult job. It was decided that the ghetto would receive food only according to its work perfomance. Now everyone had to work, so that the already reduced rations would not be decreased eyen more.

A further decree

of the Field Commander was that all Jews had to register their

valuables, money, and movable and immovable property within the

country and abroad. Property worth more than 100 DM was confiscated

and became the property of the occupying forces. Of course this decree

made us seek ways and means to save whatever we could. At night and in

the early morning people worked in attics and dug secret hiding places

in cellars and within walls. We hardly knew how or where we could hide

something most safely. Of course it was easier for those who had a

garden or similarly convenient places available to them. In the

meantime, Soviet money was exchanged. Ten rubles were now worth one

Ostmark. IV. A Jewish police force was set up, and the Riga jeweler Michael Rosenthal took on the job of leading it. He tried to maintain discipline and acted in a very decent and correct manner. For support he chose some of the intelligent young men, who literally sacrificed themselves for the common good. Of course it happened from time to time that they had to come and get people and put them into work crews, causing dissatisfaction; but after all, this was only done in our own interest, and the well-being and order of the ghetto required these measures. Besides Prefect (Police Chief) Rosenthal the following comrades were on the police force: Berel, Bag, Wazbutzki, Soloweicik, Schatzow, Berner, Ginzburg, Landmann, Gutkin and others. The reader will hear more later on about the German Jew Wand, who was also on the police force. In any case, all of them risked their lives during these difficult times in order to help us. The members of this police force wore uniforms. They wore blue caps with the Star of David. In the cellars of the Committee the former Saeima deputy and lawyer Wittenberg collected holy objects and other valuable antiques (Talmuds, Torahs, and so on). He also founded and headed the Bureau of Statistics. In one single outpatient clinic, the physician Dr. Josef tried with all his might to alleviate our sufferings. During the ghetto's short lifespan our doctors performed virtually superhuman feats. Because there was no room in the clinic for all the patients, they treated other patients at home, voluntarily and free of charge. One could see Dr. Mintz and Dr. Kostia Feiertag going to visit their patients day and night. And the other doctors were no less committed. There were plenty of medicines in the large ghetto: Every individual had supplies of medicine and besides, the ghetto did not exist for very long, so the supplies were sufficient.

After the first

few weeks it became obvious that the sanitation conditions were

catastrophic. The city government refused to pick up any kind of

refuse. Thus we were forced to dig huge pits in the courtyards so that

garbage and other refuse could be disposed of. The result was that,

although it was winter, the air was heavy, bad and polluted. If the

ghetto had existed any longer, an

epidemic would inevitably have broken out. Probably this was our

enemies' final goal! V. In the early morning hours, while it was still dark, the work crews had to assemble in Sadovnikova Street and some of the side streets. From there they marched, accompanied by a representative of their respective work stations, to do the tasks assigned to them. The largest work crews, which I will report on later, were those assigned to the Field Headquarters, the Billeting Department, the Gestapo, HVL, Knights' Hall, the Army Vehicle Park (HKP) and many others. Besides these work stations, many people also worked in the ghetto itself. Before the ghetto was closed, a large work crew was sent to Jumpravmuiza to build barracks for the new arrivals (see the chapter on Jumpravmuiza). The intelligentsia among the Jewish women set up a large ghetto laundry, in which people worked very hard. Mrs. Singel, Mrs. Trubek and others worked here under the guidance of the wife of Dr. Eljaschow the lawyer. Over time, even a Technical Authority was set up. Its first task was an attempt to set up a public bath. In the meantime, the committee was very busy setting up certain training courses. I too submitted a project for training workers to do weaving both by hand and with mechanical looms. I also wanted to set up an adjoining knitting workshop. I proposed that the engineer IlIia Galpern (of the textile factory) be the technical director. Because of the short lifespan of the ghetto, none of these many plans could be implemented. Among other things, the Jews now had to work as janitors, and people who had formerly played a grand role in society could now be met on the streets holding brooms in their hands. Because of the food distribution system, a great many people had to work in the shops newly opened by the Economic Authority. Of course those who worked in the work crews outside the ghetto tried to scavenge food for themselves somehow; but it was extremely difficult to smuggle food into the ghetto as they returned. My son worked in the Kassel construction crew, but only for a very short time. They were renovating a huge building (which was no longer part of the ghetto) on the left side of the ghetto gate. It had been assigned to the guards. This work made it very clear that the liquidation of the ghetto came very suddenly and that nobody had expected it. The Labor Authority had issued a limited number of special yellow working papers to specialists. Some craftsmen who were judged excellent received a special certificate marked "WJ" for wertvoller Jude (valuable Jew).

All too soon, a sad piece of news reached us. About thirty young girls and two young men had been sent to work in Olaine near Riga. After they had done their work, the Latvians took them to a nearby woods, shot them and plundered all their possessions. This incident caused extreme consternation in the ghetto and practically caused a panic. Moreover, on 14 November 1941 three women who had worked in Knights' Hall had been simply taken away and shot on the beach. Their boss, General Jeckeln, had by pure chance walked past the kitchen where they were working and seen that they were smoking. This was enough for him to order their immediate execution. One of these women was the wife of A. Tukazir, who had owned a wine business. The next day the entire work crew at Knights' Hall was arrested, together with the Oberjude (head Jew) Folia Zacharow. For about twenty-four hours their fate was completely uncertain, but then they were released. Every day news came from the work stations about people being arrested or taken away. For example Gorew-Kalmanowitsch, the former technical director of the "Frühmorgen" (Early Morning) and "Segodnia" (Today) newspapers, was arrested at his work station in the furniture work crew on Gogol Street. It was said that this arrest had been ordered by a former errand boy at "Segodnia", Danilow-Milkowski, who was then working for the Gestapo. All of us Jews knew him only too well. He ordered Gorew to explain to him exactly where he had hidden his possessions. He was told the addresses of various Aryans and went to them immediately, but nobody handed anything at all over to him. He did not attain his goal until he went to these people again, this time together with Gorew. Although he had promised to release Gorew, Danilow had him taken to prison, where he was shot.

There were also

suicides. For example, Mrs. Chana Meisel poisoned herself, her two

daughters Minna and Rasik, and her small four-month-old grandson. VII. Now people slowly grew accustomed to life in the ghetto, and in spite of all the difficulties they did not give up their hope for better times. The Committee also dealt with the question of schooling. Some teachers from the Sabiedriska college-preparatory school were already teaching small groups in the Committee's building. In the meantime, the issue of heating became especially urgent during the harsh winter of 1941 . If the ghetto had not been closed so soon, this would certainly have led to a catastrophe. To cover various expenses, the Committee levied a tax. An extraordinarily large amount or money was collected, but it was confiscated by the Gestapo even before the ghetto was liquidated. Later on, many people said that the Committee had certainly made mistakes, because with such a large sum of money they ought to have managed to annul the gzeire, or command to liquidate the ghetto. There were no houses of prayer in the ghetto. People prayed in the private quarters of Rabbi Zack and at various other places (Abrahamsohn, Katolu Street).

There were also

several attacks in the ghetto. For example, on the first Friday night

we received a "visit" in our house at 2 Maza Kalna Street. Drunken

Latvians and members or the German Wehrmacht (army) had climbed

over the ghetto fence. They robbed and beat us. Because our police

force was completely unarmed, their intervention did no good

whatsoever. Of course the people in the building were extremely

agitated. Because the front door was locked, the attackers broke a

window and climbed in through it. They brutally assaulted the

defenseless women. Later, a rumor arose that German deserters were

hiding in the ghetto. VIII. In our small apartment, my wife proved her great skill as a housewife and arranged everything as comfortably as possible with the few belongings we had left. Food was distributed in very small amounts, and people began to hoard it for future consumption. Already even potato peelings were being used in various dishes, and the new "ghetto specialty", liver paste made from yeast, could be found everywhere. In their free time our friends and acquaintances often gathered in our room. Because some of the men were already missing, most of the time there were more women. All the important current affairs were aired. Among the people who came - all of them later died, unfortunately, were Mrs. Pola Galpern, Zilla and Roma Pinnes, the lawyer Juli Berger, (Prince) Rabinowitz, Moritz Lange and his wife Beate, Simon Jakobsohn, Mrs. Chaikewitz, Dr. Prismann's wife and others. Many good acquaintances of ours also lived nearby (Mrs. Mila Jakobsohn. Dina Genina, Dolgicer and others). On the last Saturday before the ghetto was liquidated, my comrade Folia Zacharow invited my wife and me to his mother's room for a tscholent (Saturday dinner) with all the pitschewkes (trimmings). A large company had come together (Prefect Rosenthal, the Ritow brothers. ivlrs. Seligsohn, Abraham Lazer and others). Except for Ritow and me, not one of these people is still alive today. My wife and I often visited the ghetto representative, the lawyer Eljaschow, in Sadovnikova Street. During the very last week of the ghetto, this great pessimist was looking at the future with a bit more hope. The reason he gave for this optimism was some conversations he had had with the authorities. All of these hopes and suppositions were wiped out by the arrival of Minister Rosenbergs, because he ordered the ghetto to be liquidated. At this time there were more than 32,000 men, women and children in the ghetto. The large ghetto had lasted for exactly thirty-seven days.

With an aching heart I now begin the chapter on the ten bloody days. Although these events took place six years ago, they are as firmly fixed in my memory as though they had happened only yesterday. And they will remain just as unforgettable for everyone who survived them. Even today it is incomprehensible to me that Boira-Oilom (God) could sit on his kiseihakowed (throne of honor) and look down upon our great catastrophe. Why didn't the earth open up and swallow the murderers of our precious family members? Why didn't the sun grow dark when it saw the mass murder of our beautiful, pure, innocent Jewish children? The ten bloody days and other similar events will remain an indelible mark of shame not only for the people that claims world culture for itself, but also for the Latvian people. The world had never before experienced the sadism and the animalistic instincts which came to light at that time. And today all of these murderers dare to demand "just treatment" and "recognition"!

Unfortunately,

humankind is only too ready to forget - but we Jews can never and will

never forget! I. On 27 November 1941, a Thursday morning, a large printed announcement was put up in Sadovnikova Street in the ghetto: "The ghetto will be liquidated and its inmates will be evacuated. On Saturday, 29 November, all inmates must line up in closed columns of one thousand persons each. The first ones to go will be the inhabitants of the streets near the ghetto gate (Sadovnikova, Katolu, Lacplesa. part of Maskavas Street and others)." The announcement included various further regulations which I can no longer remember today. The decree hit the ghetto like a bolt of lightning, and total chaos broke out. Sadovnikova Street was swarming with people, and the work crews that had been standing there were not let outside until later on. People stood stunned before the momentous announcement and kept trying to puzzle out the meaning of the words "liquidated" and "evacuated". Nobody could imagine that behind these two terms something dangerous and catastrophic was concealed. It was decided that Vilanu Street and half of Liksnas Street had to be emptied of their inhabitants by the evening of 28 November. All the inhabitants of this block were driven into the interior of the ghetto. Work on the new fence around the diminished ghetto was begun immediately. The two streets looked as though a pogrom had taken place there. They were strewn with belongings that had been thrown out, and feathers from burst bedding were flying around everywhere. There was only one topic of conversation: the evacuation and preparations for the journey. The larger work crews were told they had the possibility of staying in the newly-formed small camp and rejoining their families later.

Three hundred

women were registered as seamstresses and sent "to work" at the

Terminal Prison. II. I now conferred with my wife and my older brother about what I ought to do. We decided that I should go to the barracks camp so that I could later have the possibility of helping my family through my connections with the outside. My son was to remain with my wife to give her support. On Friday evening I went once more with my wife to Dr. Eljaschow. In his room we met many acquaintances. I told him of my decision, and he also thought it was good. Of course nobody really knew the right thing to do I spent the last evening with my family at home. My wife made supper using the best food supplies we still had, and we talked till late that night. We agreed that if we should be torn apart, each of us would send his address in a letter to the Abe Ziw family in Palestine immediately after the war. We didn't sleep all night, and in the early morning hours I went one more time to my many relatives to bid them farewell, as though I already suspected I would never see any of them again. I had to go to work, and I now said farewell to my wife and my son. For a long, long time we stood there, our eyes filled with tears. My dear wife tried to comfort me by saying repeatedly that we would certainly meet again soon.

I went to work,

and my son accompanied me for a short distance. III. Very early on Saturday morning, 29 November 1941 the columns of people to be resettled assembled on Sadovnikova Street. Our work crews, which were also standing there, did not know for a long time whether they would be let out at all. The first resettlement column had to stand next to the ghetto gate. Its leader was Dr. Eljaschow. He was wearing his elegant black fur coat with a blue-and-white armband. The expression on his face showed no disquiet whatsoever; on the contrary, because everyone was looking at him he made an effort to smile hopefully. At his side one could see:: Rabbi Zack, who was somewhat shorter. Many well-known citizens of Riga were in the columns. for example old Wolschonok with his blind brother, Lewstein the banker, and many other prominent figures from our midst. SA members in their brown uniforms kept arriving continually: among them were Altmeyer and Jäger. The Latvian murderer Cukurs got out of a car wearing a leather coat, with a large pistol (Nagan) at his side. He went to the Latvian guards to give them various instructions. He had certainly been informed in detail about the great catastrophe that awaited us. The guards had been strongly reinforced, and large amounts of schnapps (liquor) had been delivered to them. After long conferences, the work crews were sent to their work stations, but the resettlement columns were ordered to go home. Of course this order caused tremendous joy in the ghetto, and people were already saying that the whole evacuation had been canceled. In the meantime, at our work station we were full of anxiety. So we sent a soldier to the ghetto to find out what was going on. He returned with reassuring news. Nonetheless we tried to get permission to go home earlier, as an exceptional favor. At three that afternoon we got back to the ghetto. We stood at the large gate, but we were no longer allowed to go in. Accompanied by the Latvian guards, we were taken to our new barracks camp. As we walked past the ghetto fence we saw that the ghetto was in an uproar. I saw many acquaintances, whom I greeted from afar. The barracks camp was already full of people who had arrived from the ghetto in the course of the day. One of them was my son with his baggage. My wife had not wanted to leave me alone. At that moment I was not at all happy about this new solution, for I had wanted my wife to have him with her for support. I looked for an opportunity to discuss the matter with her once more. A ruined building in Vilanu Street was assigned to our work crew as our shelter.

We started to

settle in anew. IV.

Habeit min

haschomaim urej!

(Look down from

heaven and see! Suddenly, late that evening the bloody evacuation began. Thousands of uniformed Latvians and Germans, all of them absolutely drunk, streamed into the ghetto and began to literally hunt down the Jews! It was a hunt to the death! Like wild animals they broke into the Jewish apartments and searched everywhere, from the cellars to the attics. People tried to hide, but these" wild beasts" dragged and tore everyone away from the most secret hiding places. They beat us and shot wildly in all directions and drove the defenseless and wounded Jews out of their houses. They tore children away from their mothers. They grabbed them by the feet and threw the poor little children out of the top-floor windows. Like tigers, the murderers ran from house to house and from room to room. They ordered people to get dressed as fast as they could and take only the bare essentials with them. Shuddering mothers looked at their small children whose hands had been broken and who could only moan in pain. The columns of people were driven from one side toward Sadovnikova Street, and from then: they were forced to march toward Maskavas Street. From the other side, the commandos wen: also moving toward Maskavas Street down Ludzas and Lauvas Streets. The columns of people were closely surrounded by Latvians, but each column was led by a German. Mounted policemen were also present. The large blue city buses were used to transport sick and weak people. They took people out of the Linas Hazedek hospital and the shelter on Ludzas Street. These vehicles drove back and forth all night and all morning. The ten Jewish drivers of the ghetto were also mobilized to transport the sick people. Only one of them, the driver Zamka, was lucky enough to come back. He too reported ghastly and nearly inconceivable events. All the vehicles and columns of people moved down Maskavas Street toward the big Kvadrats rubber factory. This was during the night of 29 November 1941, the tenth day of the month of Kislev. A bloody night, a bloody morning! Blood flowed in the streets, and in every street lay people who had been shot dead. Blood, blood everywhere! Everyone was driven forward toward Salaspils. There, at the Rumbula station near the forest, the Germans had already prepared graves. It was said that Russian prisoners of war had been forced to dig these graves. Men, women and children were ordered to strip naked in the bitter frost. They had to stand this way for a long time. They were beaten terribly, their gold teeth were pulled out, and finally they were pushed to the edge of the graves to be shot. Many women fainted from fright before they were killed. Small children were thrown alive into the graves. Many who were merely wounded threw themselves voluntarily between the dead in the open graves in order to die with them. Women and men embraced in farewell in the face of death. The luckless ones stood there in their thousands and had to wait their turn, watching their brothers and sisters being shot. Vehicle followed vehicle. When one was empty, the next one arrived. The adults' hair literally stood on end, and the children were stiff with horror. The religious Jews said their vide (prayers) before the schchite (slaughter). Quietly and calmly they said a prayer to God: "Eil rachum wchanum!" (God, have mercy!) and submitted willingly to death.

The earth still

heaved for a long time because of the many half-dead people. The

Germans had taken over the watch. Did they perhaps fear that the

murdered people would rise from their graves? V. The bloodbath was ended on Sunday, 30 November. The partial evacuation was stopped, and only the murderers moved through the ghetto, still shooting. The Jews crept out of their hiding places and whatever holes they had found and looked around them to see whether the Latvian and German gangs were still there. Ludzas Street in the center of the ghetto was full of murdered people. Their blood flowed in the gutters. In the houses there were also countless people who had been shot. Slowly people began to pick them up. The lawyer Wittenberg had taken this holy mission upon himself, and he mobilized the remaining young people for this task. Back and forth drove the hearse, collecting all the corpses and taking them to the old Jewish cemetery. Those who were already half-dead were also taken away and died on the way. Blood flowed like water! Large common graves were dug in the old Jewish cemetery. Certainly more than a thousand murdered people were buried in each of them, and it was no longer possible to record exactly who was among them. The Latvians also brought Dr. Freidmann's family to the cemetery. His wife and his child, although they had been shot, were still alive. Only here were they shot dead, and after that Dr Freidmann himself was forced to bury them. Bernhardt, the son-in-law of Maikapar (owner of a cigarette factory), was also brought to the cemetery from the city, where he had hidden with his wife and children near Baltezers (White Lake) in Jugla. He had been betrayed by an Aryan woman who was after his property. He and his family were shot. Only he was Jewish, for his wife came from a well-known Karaim family. The same fate overtook Bernhardt's mother and his two sisters. The Aryans who lived in the surrounding houses cold-bloodedly watched all of these events in the ghetto. Of course the news of our great catastrophe was immediately circulated in the city. Through this operation, all the inhabitants of Sadovnikova Street and all the streets near it (Katolu, Daugavpils, Jekabpils, Ludzas and Liela Kalna Street, as well as part of Maskavas Street) had been exterminated.

This bloody night

and the following morning had swallowed up more than 15,000 men.