|

Blood, Fire, and Columns of Smoke

By Yitzhak Golombeck

I. Zambrow – My Birthplace

Who among us

from Zambrow does not remember our shtetl with its precious young people, with

its

synagogues, its Yeshiva, with its skilled craftsmen, and its

workers, who brought honor to the

Jewish

populace, depriving the gentiles of the canard that Jews are only

fit to conduct trade: Jews

in Zambrow

plowed, sowed, and also reaped.

While being

a shtetl of Mitnagdim – Zambrow also had a reputation from its

Hasidim.

In the ‘Red

Bet HaMedrash'

(called that because it was built

out of red bricks) it was mostly the

occupiers of

land that worshipped. In the ‘White Bet HaMedrash’

as it was called in the final years,

the Bet HaMedrash of the craftsmen, one could come to hear

all the wonderful

Maggidim and

orators,

that appeared before us in our shtetl. The beautiful Zambrow synagogue was a

center for the

town’s

intelligentsia. There, on the High Holy Days, one would encounter

Jews, who for the entire

cycle of the

year, had not sat down in a Bet HaMedrash. The synagogue graciously

took in all those

who came to

collect funds for the benefit of the Land of Israel. Neighboring the

White

Bet

HaMedrash ,

was the so-called ‘shtibl,’

the [sic: spiritual] home of the Hasidim of Zambrow.

The ‘Zionist

minyan,’

could be found in Salkind’s house, where the activists worshipped

with

Koczor and

Rawikow at their head.

The Jews of

Zambrow founded a Manual Trades Bank, a Gemilut Hasadim Bank, and a

Bikur

Kholim .

Zambrow, which had been small, became a city and a magnet for Jewry.

Zambrow, the city

of

merchants, craftsmen and land leasing, did not know much of the

bitter need and deprivation,

which never

left all the other surrounding small towns. There was a large

military camp here, and

twice a week

there were market days.

In the years

1934 and 1935, Zambrow began to feel the heavy hand of the risen

Narodowa Party 40

they began

to boycott Jewish businesses, and beating Jews in the streets. Life

became difficult, and

unbearable.

Young Jewish men organized themselves in order to offer resistance.

Once, on a market

day, it was

on a Tuesday, peasants, who had arrived from the surrounding

villages launched a

pogrom. They

tore out paving stones, and used them to knock out the panes of

windows, while

robbing

stores. Many Jews were wounded. That day remained in the memory of

Zambrow as ‘The

Black

Tuesday.’ It was from that ‘Black Tuesday’ that all of the trouble

started which Zambrow had

to

withstand, in the coming years, until its demise.

The young

people of Zambrow began to look for ways and means to flee. With

great difficulty and

the

expenditure of much energy, a very few managed to get to the Land of

Israel. Many other young

people left

their ancestral home at that time, and undertook to go all over the

world, without any

specific

goal in mind.

II. The War

Between Poland and Russia

A

Market Day

The outbreak

of the war between Poland and Germany heralded the destruction of

the Jewish

communities.

In the year 1939, I returned to Zambrow from the front, as a Polish

fighter. It was

difficult to

recognize the shtetl.

The side, in the direction of

Lomza, and the left wing of the

marketplace

lay in ruins, gutted by fire. [Also] the Red Bet HaMedrash went up in smoke, the house

of the

Yeshiva, the White Bet

HaMedrash, and all the

surrounding houses. Upon my arrival in

Zambrow, the

Germans were still there. We had no roof over our head, but my

family was intact, and

I later

heard from people that the Germans still held back their hands from

murdering, and did not

touch anyone

in the shtetl.

However, a fragment of shrapnel pierced a store, and Leibl Golombeck

and an

additional number of Jews, whose names I do not remember any longer,

fell at that time.

After the

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Germans pulled back to the second side

of Szumowo,

meaning to

the Bug River, which was a natural boundary between Germany and

Russia, after

partitioning

Poland.

When the Red Army entered our area, we were overjoyed: the dark

terror that weighed heavily on

the burned

down and impoverished city, lifted, and there was dancing in the

streets, the joy being

so great –

we had gotten rid of the Nazi murderers!

Life in

Zambrow began to normalize itself in accordance with the Soviet

style. It was our communist

youth that

had a large part, in the introduction and establishment of the

communist way of life. The

gentiles

immediately changed their skin, and changed their appellation of the

Jews away from shame:

no more

would be heard ‘zyd-kommunist’

or ‘zyd-spekulant.’

The communist régime did not tarry,

and it

sentenced masses of Jews for the crime of ‘speculation,’ for long

years of prison.

Slowly, life

acquired a certain normalcy to it. Commerce came to a standstill.

The balebatim

got jobs

in the

government. The larger houses in the city were nationalized. New

houses began to be built.

III. The

Expulsion of the Jews of Ostrow-Mazowiecki Begins

Like an

outpouring that comes from a broken dam, Jews began to come

streaming, across the border,

into our

city. The Germans, on their side of the border began their work of

extermination. Thousands

of people

sat in the streets, without a roof over their heads, and Zambrow did

everything within its

power to

help, and lighten the suffering of the refugees. Meanwhile, the

Russian authorities looked

away at

those events transpiring in our street. But not for long. Some time

later, the Russian

authorities

began to look upon the Jews as spies for Germany, and shipped them

off en masse to

Siberia.

Tens of families remained living with their Zambrow relatives, until

they were later

transferred

to Slonim. Our young people were mobilized by the Russians and sent

to Russia to serve

in the Red

Army.

IV. The Russian War in 1941

|

|

|

|

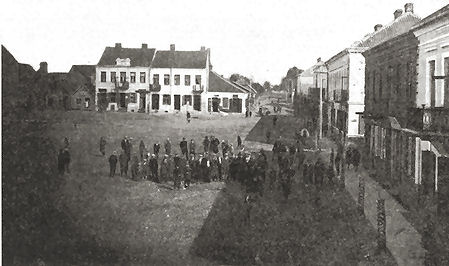

Soldiers Drilling in the Marketplace |

|

A

Spot in the Marketplace

|

The Germans

had taken possession of our region beginning from the first day of

the war. On the

second day,

German patrols roamed the streets. In the month of June 1941, the

Germans called

together the

activists of the shtetl

and said, that they want to

have a Jewish representation for the

Jewish

populace. It was at that time that the first Judenrat was created, with R’ Gershon Srebrowicz

at its head.

The first demand, that the Germans put forward, was – a financial

levy. It was the

responsibility of the head [sic: of the Judenrat]

to provide this ‘contribution’ in the sum of hundreds

of thousands

of gold marks, a levy which the German authorities imposed on the

Jewish populace.

A failure to

provide this contribution at the precisely designated time, placed

the lives of tens of Jews

in jeopardy.

The demands of the Germans became ever more difficult and

oppressive. They began

to seize

Jews and send them to work on the digging of trenches near the

Zambrow barracks. Among

those

seized, on one day, was my father vg.

My father told us that, at work, an officer approached

him and

asked: ‘Jew, what is your occupation? – ‘I am a tenant farmer,’ my

father replied. The

German then

screamed at him in a wild voice: ‘You lie, Jew, you are lying!’ He

went off, and asked

other Jews

about my father. Discovering that my father had told the truth, the

German called my

father away

to a side, and asked him to stand on a bench. He called together a

number of Germans

to look at a

Jewish tenant farmer. He questioned my father about his family,

about the children, and

wanted to

know if the children are also tenant farmers. After work, he gave my

father a loaf of bread

and told him

never to come back to work on the digging, but to remain at his work

on the land. When

our father

told this to us, we understood that we needed to hide ourselves...

Living in

Zambrow became increasingly more bitter from day to day. One early

morning, the

Germans went

into the Wander Gasse,

and they seized my uncle Leibl

Slowik with his son, Moshe,

the old

cow-herder and his son-in-law, Leibl Dzenchill, and other additional

Jews, whose names I

no longer

recall. They were taken away – and we never saw them again alive. We

were told that they

were working

here, or there, on roads, and similar stories...

After this

incident, Jews began to hide themselves, avoiding the possibility of

appearing in the streets. The

Germans then took to the

Judenrat demanding they

provide people for labor, most of

them for

work in the Zambrow barracks. Regarding the ‘contributions,’ the

Judenrat failed, not

having the

resources to satisfy the very high German demands. The members of

the Judenrat were

beaten

murderously more than one time. In the end, the Germans dissolved

the Judenrat.

They found

a Jew named

Gl icksman, and gave him full power to set up a new Judenrat on a completely different

basis. Glicksman, a scion of Grudzonc, was an assimilated Jew

without any Jewish feelings, and spoke

the German language. He verbally abused the Jews, had bad names for

them, and raised his voice to

them even higher and more sharply than the Germans. His power over

the Jews was practically

unconstrained. His police – stern and insolent. If it happened that

they could not get what they wanted

in a gentle way, they knew very well how to extract it with

severity.

V. The

Sorrowful Tuesday

Tshizev

Street

The order

was given that on August 19, at 5:00AM, all the Jews in Zambrow were

to assemble on

the

marketplace. All, except for the small children, have to be in the

street. Anyone that will be

encountered

in a house, will be shot on the spot. Glicksman issued this order.

His police force then

went from

house to house to inform everyone about this issued order. There

were many craftsmen

that worked

in the surrounding villages, so Glicksman’s messengers traveled

there and brought them

back to the

city. They were told to dress themselves in their holiday finest.

Various rumors began

to spread:

some said they were to be taken to work; others said that they were

looking for

communists.

On the day

of August 8 41,

at 5:00AM, young and old alike in Zambrow, found themselves on the

marketplace.

At about five o’clock, there appeared armored vehicles with S.S.

troops in them, armed

with machine

guns. They took up a formation surrounding the marketplace. We were

arrayed in rows

like

soldiers. And then the ‘work’ started. Incidentally, the Poles knew

how to keep a secret, that they

[sic: the

Jews] were to be taken away and killed. They stood behind the

houses, and looked out from

corners

towards the marketplace, waiting for the moment, when they could

begin the work of

plundering

the abandoned city. We, from our places in the marketplace, could

see how the company

of Poles was

forming itself, with bands around their arms. It became very clear

to us, what it was that

the Poles

were intending to do.

The

selektion then began. The bandits went about

between the rows, and selected the best of the

young men,

and women, and took them out of the rows. They were immediately

arranged in groups

of five,

facing the direction of Lomza, diagonally opposite the Tshizev

Street. I was standing with

my father

and mother, and my two brothers, Israel and Yankl. My brother Moshe,

and his wife, stood

in a second

row. A thought dawned on me and my youngest brother: since another

row was formed,

selected by

Glicksman’s men, we were not to stand and wait for the S.S. troops

to come to us, and

we ran over

to the second side of the street, and placed ourselves in that row.

And this is how I saw,

five minutes

later, how my father with my brother Israel, and the brothers Meir

and David Bronack,

came to the

general row. We stood facing the direction of Bialystok. Later on,

it became forbidden

for us to

look at the second side. I will recall here, that for the elderly in

the city, with Rabbi

Regensberg

at their head, the Germans brought a big freight truck, and took

them off in the direction

of Warsaw.

Meanwhile

the groups were closed. Our group became filled. My brother Moshe,

and his wife, were

the last

ones that finished out the large row, that was headed towards Lomza.

The order came to

march. The

first to move was the group facing Warsaw. After them, we went off

in the direction of

Tshizeva,

The group headed toward Warsaw was guarded by Poles carrying staves,

all from

Zambrow,

well-known among the Zambrow populace, and by the S.S. troops. The

wailing and

keening was

indescribable. Mothers ran after children, and children after

parents. The Germans

opened fire

to drive people off the marketplace. The wailing and crying could

continue to be heard

even very,

very far from the city. Little children without parents, parents

without children. Entire

families

were eradicated at one time. A terrible sorrow fell upon those who

were left behind. The

little

children, who remained without parents, were divided up among

families. I took I took Chaim

Kuropatwa’s

child. He was called Yankl, and he became our child – until

Auschwitz.

VI .

Dealings with the Germans about a Ghetto

A

Street in Zambrow

The Germans

cordoned off the streets that ran parallel to the Tshizev Street,

that is, the Jatkewa and

Neben Gasse,

which was to include Szliedziewsky’s and Dembrowsky’s factories, and

the river

should be a

boundary line. The burgomaster of the city was Augus t Kaufmann, the

German, who

lived

diagonally opposite the cemetery. He confiscated Szliedziewsky’s

wealth from Gedalia

Tykoczinsky

kz, and

from Dembowsky – our yard along with the buildings. It looked like

the deal

was done,

but something behind the scenes caused them to regret this and walk

away from

abandoning

their businesses. For us Jews, this change was a matter of great

significance. It meant

that we

would have more room for those who would be taken into the ghetto.

Because of this change,

things all

of a sudden quieted down. And since the space on the two small

streets was too crowded

for the

those Jews who remained, rumors spread that the town council had

taken a decision to

approach the

Germans, and ask them to take away another couple of hundred Jews,

asserting that the

severe

overcrowding in the ghetto would endanger the health of the

Christian populace, which, by

the way,

would be separated from the ghetto by a barbed wire fence. In the

meantime, they began

to build a

fence, and in the corner of the Bialystok road, near Kaufmann’s

house, a tower was

erected. It

became clear, that this enclosed area had been designated to be a

ghetto.

VII. The New

Aktion

The Town on a Saturday

Two weeks

and two days later, the Germans again ordered the Judenrat to call all of the Jews

together on

the marketplace, with the same warning, that they will shoot anyone

on the spot, who

failed to

come. Everyone has to appear at the designated location on the

marketplace. Everyone,

except

children. This notification from the Jewish police, engendered a new

outbreak of panic, which

was

anticipated, because they no longer forcibly dragged people along.

Whoever could hide

themselves

did so. I, the rest of my family and the little Yankeleh Kuropatwa,

spent the night at our

colony under

the open sky. At seven o’clock in the morning, the peasants, who had

come to the city,

were

intensely amazed, when they found us in the field. They brought us

the tidings, that the

Germans had,

once again, led off many people, men and women. At ten in the

morning, I was already

at the yard

on the Lomza Gasse.

The Poles had come to see if any of the Jews remained, fully

prepared to

seize booty. And when they saw me and my brother Yankeleh, they said

to me, in

amazement:

‘You are still here?’

It was

harvest time. And since we had just constructed a new barn,

small-time peasants came to us,

and asked if

they could place their grain in a small corner of the barn. Their

intent was premeditated:

since they

expected that I would be taken away, they would come to reclaim the

grain they had stored

with me, and

who would be there to keep them from taking everything?

It was

Thursday, September 4. Many people were missing at that time, and to

give orders to others

as to what

they should do, was not possible. Everyone dealt in a way dictated

by their own common

sense. As we

were later told, the Germans raised a hue and cry that they were

short on Jews. We

thought that

the Germans needed Jews to do labor, and therefore, as a result,

they would take only

the able and

young. Accordingly, everyone made an attempt to appear worn out and

old. Women put

kerchiefs on

their heads. The intent of the Germans this time, however, was much

worse than before.

They seized

people randomly, young and old, even pregnant women. ‘They are

taking us to the

slaughter’

the terrifying thought stabbed in our minds. That morning, they were

led off in the

direction of

Bialystok. And as we later found out, they were killed in a forest

near Ruti Kasaki. May

the Lord

Avenge Their Blood.

VIII. The

Preparations to Occupy the Ghetto

‘Now there

will be enough space for the Jews,’ the Poles were heard to say. The

Zambrow ghetto

was created,

but all the Jewish tenant farmers were obliged to remain on their

places outside the

ghetto, and

work their fields. This was the wish of Kishel, the German land

farming inspector. It was

harvest

time, when the grain needed to be gathered in, the potatoes dug up,

and to get ready for the

winter

planting, and he therefore had need of the hands of the Jewish

tenant-farmers. The entire

population

of the ghetto derived help during that time by this. When a Jew was

caught outside of the

ghetto, he

would say that he had been working in the fields with a Jewish

tenant-farmer – and this

was

legitimate.

At the end

of September 1941, we were given no more than fifteen minutes of

time to go out, that

is, to leave

our houses, the barns with grain, the machines, horses and cows –

and return to the

ghetto. My

mother, myself and my brother Yankeleh, were taken in by the family

of Yudl Eusman.

Together, we

were in a two-story house – the Eusman family, Alter Dwozhets and we

three.

IX. Life in

the Ghetto

It was a

hard and difficult life. We had many orphaned children. Also,

parents that had lost their

children.

Fate, however, declared, that there would be some solitary families

that remained intact.

The Zambrow

ghetto became a place of refuge for Jews from the surrounding towns.

The ghetto was

literally

the center and gathering point for workers, that the Germans drew

from there, for labor

gangs to

build and pave streets and roads. Our gang worked at breaking

stones, and pouring asphalt.

All of the

Jewish workers worked only for the Germans. there was a gang that

worked in the

Zambrow

barracks, where the Germans had created a camp for Russian prisoners

of war.

We lived in

the ghetto under a despotic régime of self-governance. Glicksman,

the ‘Chief Jew’ has

a police

staff under him, and ruled his kingdom with a high hand.

X . A Typhus

Epidemic in the Ghetto

The

thousands of prisoners in the Zambrow camp fell victim to hunger and

typhus. The typhus

disease was

carried to the ghetto. It was said that since the surrounding fields

had been made filthy

with the

fecal waste from the barracks, that the cucumbers that we ate from

those fields carried the

typhus

bacteria.

Near the

river, in the ghetto, we had a hospital. The doctors were Dr.

Grundland and Dr. Friedman.

The Head

Nurse was Masha Slowik. Their dedication was without limit. But

their reach was to

limited to

be of help.

Here, in

praise, I wish to recall the lady, Elkeh Kaplan

kz, a truly

righteous woman, who collected

kasha,

grits, potatoes, and cooked up a bit of food for the abandoned

orphan children.

The ghetto

did not know any spiritual life. There was no

Bet HaMedrash,

no school, and there were

no resources

to be found in the ghetto. In the last months, the Germans permitted

the transfer of a

new,

unfinished house from outside the ghetto. The house was moved, and

was set up on the account

of the

owner, Sender Kaplan. This house became our Bet HaMedrash.

In the

meantime, a variety of news reached us, brought by refugees. They

told of Treblinka near

Malkin. The

human mind could grasp, and then not grasp what this meant. However,

we did grasp

that we,

too, were exposed to the danger of extermination.

We also

received a variety of false reports. Regarding the people, who were

led away on Tuesday,

we were told

that they were seen working on a road in Ostrow-Mazowiecki. All of

these reports

came from

gentile mouths, from Poles, that the Germans put up to this. There

is a story about a letter

from David

Bronack, which a Pole named Klosak brought. This Pole had worked

steadily for Yossl

the Painter,

and we knew him well. He demanded 150 marks for the letter from

Rivka Bronack. She

immediately

came running to tell me the news, that the people are alive. We gave

the Pole 150

marks, and

he gave us the letter. He told us that David Bronack gave him the

letter, and apart from

this, we

could not get another word out of him. In the letter the following

was written: ‘We are alive

and are

working on the roads.’ Sadly, neither Rivka, nor her son Moshe,

could recognize David’s

handwriting,

but because of the many errors that we found in the letter, we

understood that this was

a

fabrication, a means to swindle us out of money.

During the

time that I still was living outside the ghetto, Poles told us that

they heard from other

Poles, who

had accompanied Jews along the way, that they were all shot in

Glebocz near Szumowo,

in an

incompletely built Russian fortification, and in this same mass

grave, many other Jews were

also buried,

who were from the area, until the substantial fort, intended for the

Russian artillery, was

filled up.

XI. Jewish

Valuables are Turned Over to be Hidden in Gentile Hands

When life

had already lost all semblance of order, all those who remained

alive, gave away a large

part of

their furniture, bed linen, and clothing, to Poles that they knew.

And on another day, it was

already

possible to see how displeased they were, to encounter someone from

the family, who knew

about these

transferred valuables. There were also instances, where Poles

immediately refused to

return any

item, that someone wanted to sell, in order to buy bread, and it

became necessary to look

for help

from the Judenrat,

meaning from the Germans, to reclaim those items from Polish hands.

The Jews of

the ghetto were like a thorn in the eyes of our neighbors, the

Poles. They would say:

‘See, the

Jews have been settled in the ghetto, and its like nothing, they are

alive. If it were us, we

would have

died of hunger within a month.’

We began

hearing rumors about the liquidation of the ghetto in September.

Beinusz Tykoczinsky

and I, once

when we went together outside the ghetto, ran into Beinusz’s good

friend Szliedzesky,

who, under

the Russian régime, held the post of Chief of the Fire-fighters

Brigade, with Beinusz as

an

assistant. Szliedzesky says to Beinusz: ‘It goes very badly for the

ghetto. This morning, we were

given an

order to set up a guard over it.’ We already knew what this meant,

because we had heard

from

refugees that the Germans always call out the fire-fighters when

they are getting ready to

liquidate a

ghetto. We brought this frightening news into the ghetto, and a

panic broke out

immediately.

Despite this, a couple of days went by, and nothing happened, and

the tension subsided.

In those

days, a group of comrades, who had left the ghetto, in order to join

the partisans in the

forests,

came back home. This matter was kept in extreme secrecy, so that,

God forbid, the news not

pass to the

Germans by way of an informer. One of the group was Yitzhak Prawda.

The group went

out of the

ghetto well-dressed, shod, and provisioned with a sum of money. In

the fields, they

encountered

remnants of the Russian army, mostly Ukrainians. The Russians and

Ukrainians beat

them, took

away their money, stripped them naked, and barefoot, and drove them

away in shame,

back to the

Germans.

Immediately

rumors about the liquidation of the ghetto started up again. As

previously already

mentioned,

the Jewish craftsmen worked exclusively for the Germans. Among them

were tailors,

shoemakers,

furniture makers, and other sorts of trades. One day, the Germans

appeared and

demanded of

the Judenrat that they gather up all work, whether

finished or unfinished, that the

Germans had

ordered. The Judenrat police went out to carry out this order. For

us, this was the

signal, that

the danger of liquidation’ was near. The ghetto residents, in

resignation, and terrorized

by fear of

death, began to look for stratagems by which to save themselves.

Whoever had gentile

acquaintances, carried off whatever remnants of goods they had, to

have them hidden, or to plead

for mercy,

that they should hide that individual himself. The work gangs

marched into the ghetto.

We gathered

at the Judenrat, and demanded that Glicksman tell the truth.

XII. Glicksman and His Truth

Glicksman

began by addressing his police, and began to shout over the heads of

the gathered people:

‘What do

they want, the dirty Jews? The Germans took away these things in

order to exchange them

for other

things.’

The Zambrow

Jews, seasoned from their troubles, and knowing their ‘Senior Jew’

didn’t take him

at his word.

When nightfall came, everyone took for the barbed wire. The barbed

wire was cut, and

we fled

underneath to the river, near Dembowski’s and Szliedzesky’s. Men,

women, and older

children

ran, with packs on their backs, to the extent that they had the

strength to carry. We fled to

the nearest

forest. I, and my mother and brother, at about ten o’clock at night,

went off in the same

direction.

In the ghetto, the only ones left were older people, who surrendered

to their fate, and

children in

cradles, that parents were unable to take along. In the late hours

of the night, when

Glicksman

saw that he was left without Jews, he, and his entire coterie also

fled and hid themselves,

out of fear

of the Germans. Those who arrived in the forest later, told that it

had already become

difficult to

get out of the ghetto, because the Germans had surrounded it.

XIII.

Zambrow Jews in the Forest

Fate decreed

that one misfortune should be worst than the next. Fleeing into the

forest, we knew, was

no

salvation. However, people, when exposed to the danger of being

killed, will run anywhere in the

world,

driven by an inner force, an impetus, that cannot be contained.

Having run a considerable

distance,

one remains standing, spent, without any strength left, and one asks

the other: ‘Where do

we go?’ The

only answer that could be was: ‘Into the forest!’ And how will they

be able to live, even

if just

being able to regain some equilibrium – men, women, and children,

hungry, beaten down,

without

help, surrounded with a murderous foe on all sides? – To this there

was no answer.

My mother,

my brother and I, dragged ourselves to the Czeczork Forest. We

sought out a hiding

place

between shrubs, and settled ourselves there. We hear people running

nearby, hearing their

heavy

breathing and mumbling. The night was long, and didn’t want to end.

Very early, we heard

a great

disturbance in the forest, the sound of a struggle. I crawled out of

my ditch, and immediately

see in front

of me a cadre of Poles, in groups of five, six, or more, with staves

and scythes in their

hands,

pushing the Jews, and striking out left and right. The Jews cry,

begging for mercy from their

beaters,

pleading with them to take bribes, ha – money, gold – that is what

they want though. Having

gotten rid

of one band, we immediately fall into the hands of a second band.

With each band, little

shkotzim

ran along, from seven to ten years

of age. They climbed under every shrub, making noise,

whistling,

shouting: ‘Żydy!

Żydy!

Żydy! I crawled back into my hiding

place and sought counsel

with my

mother and brother, as to what we should do. I had just begun to get

back into our ditch, and

we have a

small shaygetz

near us, and he is shouting at the

top of his lungs: ‘Żydy!

Żydy!

Żydy!’

He

lets out a

whistle, and the adults immediately came running. As soon as they

saw us, they remained

standing,

and called out, ‘Oh, Jesus, the Golombecks!’ They covered the mouth

of the little rat, and

sat down

next to us. As beaten down and broken as we were, we burst out in

tears.

Who were

these shkotzim?

A person named Proszenski lived on our street. His sons worked for

us as

shepherds. In more recent times, one of them worked for August

Kaufmann, the burgomaster

of the city,

and sitting on the ground with us, beside the shrub, he told us: in

the city placards were

hung about,

which carried the notice that for the number of Jews that will be

apprehended and

brought to

the gendarmerie, a reward of an amount of money and a bottle of

whiskey will be given.

I was able

to sense that they had already gotten the whiskey. The placard also

warned that, whoever

would hide a

Jew, will be shot on the spot.

It was under

these circumstances that the bandits from the city went into the

forest – and after them,

came the

bands [sic: of predators] from the village.

They let us

go free, and we proceeded further. After each bit of the journey,

that we took, they

confronted

us. They robbed us, and took away whatever they could find that we

had. There were

those among

them who did not allow themselves to be bought off. They did as

follows: One of them,

who was

their representative, first robbed us, emptying what he could of the

Jews, after which they

began to

beat and drive the people further. The seized a couple of tens of

Jews this way, and drove

them into a

barn in Czeczork. There, others were waiting, who led the Jews into

the city. At first,

resistance

was offered to them, struggling with the assailants. In the end,

however, it was necessary

to

capitulate. We were too weak to defend ourselves against murderous

enemies, who only wanted

our deaths,

in order that they could have all our assets, which would remain as

booty for them to

plunder.

There was not a single Christian family that didn’t have one sort of

Jewish valuable or

another in

their possession.

In this

manner, the Poles rounded up hundreds of people that day. When the

sun was getting ready

to set, we

also were apprehended, and driven into the barn, which we found to

be full of captured

Jews. They

robbed us of our money, watches, good clothing and shoes. We

gathered up money

among

ourselves, dollars, and shoved it into the hands of the leader of

the Polish band from the city.

It was now

clear to us, that they will enthusiastically lead us to be killed.

XIV. We

Leave Our Mother in the Forest

Night fell.

Again, I sought counsel with my mother, as to what we should do. One

of the members

of the band

told us, after he had received money from us: ‘Run!’ So my mother

said: ‘Children, if

you can save

yourselves, run away from here! Let at least a memory of this family

remain.’ The first

one to run

was my brother Yankeleh kz.

And as soon as Yankeleh went off, my mother said to me:

‘Yitzhakl

try to save yourself.’ It was difficult for me to get myself moving.

I was suffering from a

broken foot

that I had gotten from an accident while working in Szumowo. Despite

this, with the

elastic

bandage, which wound around my thigh down to my toes, with all of my

strength, I undertook

to flee with

all of the others. In this way, I reached Bielicki’s garden. There,

I hid myself in a field

booth – and

had a long bitter cry.

In the still

of the night, yet another cry was carried in my direction, the

crying voice of someone who

thought they

were talking to themselves:’ There no longer is a mother, there is

no longer a brother,

alone like a

rock.’ I tear out of the booth, and I run to the fence. I call out:

‘Yankeleh!’ – but I didn’t

see him any

further. In the morning, my neighbors told me that Yankeleh stayed

with them, and left

in the

night, and they do not know where he went. Later on, I was also

told, that had he not left

immediately,

he would have been taken away with all of the others to the Zambrow

barracks.

Glicksman,

and his men, as I heard it told, presented themselves to the

Germans, and he will be the

‘Senior Jew’

in the concentration camp.

XV. My

Third Day in the Forest

With the

setting of the sun, the Germans surrounded the forest, and opened

fire. After that, they

penetrated

deeper into the forest, accompanied by Poles. They again trapped a

lot of Jews in their

dragnet. The

truth of the matter is, that life had become repulsive to these

people, and almost all of

them had

decided to give themselves up.

The Poles

did not permit any Jews to come into their homes. When they sold you

a bit of bread, they

demanded

that you immediately go away.

In the

garden of a peasant, I found a pit full of potatoes, which had a

cover with a small door. That

is where I

made a place for myself to live. During the day, I wandered about

the fields. At night, I

went into

the potato pit. I loitered about this way for two weeks, in the

field and in the pit. With each

passing day,

I saw fewer and fewer Jews. The Poles told me that all are going

into the barracks of

their own

free will, and they are given food there. the peasants provide

potatoes for the camp.

Hearing that

the people were alive, I decided to give myself up and go to see if

I could help my

mother.

After 14 days of living in a pit, I presented myself to the

gendarmerie. I was led to the

ghetto. That

was the gathering point for all the apprehended Jews, and those who

came of their own

volition.

The fire fighters escorted the captured as far as the barracks. I

asked to be allowed to go into

my home, to

take a towel. I was permitted to do this, but not to take any more

than fifteen minutes.

I could not

negotiate the street in the ghetto, which was covered in mountains

of pots, bottles, pieces

of

furniture, utensils, shoes, linen, clothing, pillows, books, copies

of the Pentateuch, and volumes

of the

Talmud. Every home – was barricaded by loose goods, that had been

extracted from the

houses. I

made a path for myself through this, to our house. The door was

broken open, and

everything

from the drawers had been pulled out, thrown about on the floor,

linens, clothing, shoes,

– the

furniture upended.

The Zambrow

Jews, who had gone off to the fields, took practically nothing with

them. They left

everything

behind, abandoned to be plundered. By contrast, the Jews from Lomza

arrived in the

camp with

bedding, pots and utensils.

XVI. The

March to the Barracks

The Jews

wore Yellow badges, in the form of a Jewish star, on the front and

back. The Jews were

forbidden to

walk on the sidewalk, being compelled to walk in the middle of the

street, where the

sewer waste

ran. Marching over then Zambrow Kosciuszko Gasse,

I saw Poles, residents of

Zambrow and

its vicinity, workers, merchants, peasants. All looked to the side,

but I saw one shikseh

who was

weeping, as she went by. This was a woman of the streets in Zambrow

whom I knew...

XVII. Entry

into the New Hell

A German

soldier with a death’s head insignia on his helmet, opens up the

stalag??? and lets us in.

Up to then,

the Poles had fulfilled their sacred mission – and then left. There

is stalag number one,

number two,

and tower number 3. Thanks to God, I too, am now in Hell. People are

running back

and forth.

Later, I found out that this was the day when the peasants had

delivered a contingent of

potatoes for

the camp. But this is a story unto itself, as we see so later on.

I inquire

about as to where Jews from Zambrow might be found. I am told, that

block 3 will be

designated

for them, and those from Lomza will occupy block 1 and 2. Block 4

held Tshizeva,

Wisoka and

Umgebung. In block 5 – Jews gathered up from various places.

When I

arrived at the block, I was surrounded on all sides. They began to

tell me about the great

extent of

the hunger. As previously mentioned, those from Zambrow fled into

the forest empty-handed;

no

protection for their skin, not a pot to cook in, and a pail in which

to hold water was totally out

of the question. In order to get water into the camp, it was

necessary to let each other down, one

over another, into a deep well. The people from Zambrow were eager

to draw water, but they had no

pail at hand – so, they are suffering this way for two weeks

already, slavering for a drop of water.

I

immediately began to inquire: ‘Who has seen my mother?’ I was led up

to the second story. In the

large

chambers, with plank cots in three levels, lost in a forest of

people, I found my mother

vg.

This is the

picture: The ‘residence’ was the middle one of the three levels of

cots, running the length

of the wall,

cots banged together from boards and poles. Shrunken in there, sat

my beloved mother.

Seeing me

approach her, she gave her self a push, tearing herself to me, but

then immediately falling

back for

lack of any strength. I jumped up onto the cot, and my first words

were: ‘Mama, forgive me,

for having

left you alone.’ With tears in her eyes, my mother said to me: ‘ But

I was the one who sent

you away. Do

you have any news of Yankeleh?’

In the

meantime, my entire family gathered around us: my uncle Slowik’s two

daughters, Chaya and

Masha, my

uncle Isaac with the children, Rivka Bronack with two daughters and

a son, and a little

daughter of

my brother Moshe, aged 2 ½ years old. She was called Racheleh. I had

brought a couple

of loves of

bread with me, and I divided this and in doing so, bought myself

into both worlds.

My mother

told me, that she is living this entire time on the ration of bread

that she receives. She had

not tasted

so much as a single spoonful of soup. Once she ascended to her place

on the bunk bed, she

no longer

stirred from there. And this was also the case with many other

women. I sat myself on the

bunk bed.

When my mother regained some of her composure, she spoke further:

‘Since I

figured that I had lost my children, and that I would not live much

longer than another

couple of

days, I took my packet of jewelry, and threw it under the bunk bed.

Since life has ended,

and there

are no children, what do I need it for?’ This packet held the legacy

of generations –

precious

stones, golden chains, rings and small watches.

The lowest

bunk bed was about ten centimeters from the ground. I went

underneath, found a stick,

and swept

the packet out from underneath.

In the

kitchen, they gave out a bit of soup and kasha. So I went down, and

got a bit of soup, ‘ vashka’

in the lingo

of the camp, in the pot that I had brought with me.

A little

later, I went down again, to see and hear what was going on

downstairs. Again a running

around, a

movement, with shooting that came immediately after it. I barely am

able to become aware

of what had

happened, that they are now first carrying dead out on stretchers.

I must say

here, that the Jews from Lomza were far more bold than the ones from

Zambrow. On that

day,

potatoes were brought into the camp, and the hungry, pity them, let

themselves loose wildly at

the

fully-laden wagons, and began to grab potatoes. The soldiers at

their posts opened fire, and about

five or six

people fell. Despite this, a number of wagons were emptied of their

contents. People fell

on the

potatoes and began to gnaw them while they were still raw, as if

they were good, sap-filled

apples.

Everyone in

the camp could not understand why I had come. There is no way back

from here. A

barbed wire

fence – and then another fence. And such surveillance! Hemmed in,

walled in, unable

to penetrate

through, and getting close to the barbed wire means a faster death

from a bullet in the

back. Death

here is sown left and right.

XVIII.

Getting Out – And Returning

A long row

of wagons, loaded with potatoes, stood outside. The peasants, who

had to wait in the line

for

unloading, came inside with whips in their hands, to take a look at

the ‘ òyds.’

In this way, I

encountered

a peasant that I knew, inside the barracks, and struck up a

conversation with him. And

in talking

to him this way, I took off the yellow star from myself, put up the

collar of my short jacket,

and took the

whip out of the hands of the peasant. The peasant did not catch on

to what was going

on. I ask

him: ‘Where is your horse and wagon?’ He says: ‘On the other side of

the fence.’ So I

gesture to

him: ‘Come out of here. Here they shoot. Why do you want to loiter

around here? Come

to the

wagon.’ We went out of the barracks and continued talking. I passed

the first guard tower

uneventfully, then the second tower, and I am now at the main tower.

My heart was pounding out of fear, but

I steeled myself. And here, I was out free. I am proceeding without

my clothes badge, in

the middle

of the sidewalk, to spite the Poles. I am stared at, indeed, with

wonder, but I continue

along my

way, insolently, with feigned haughtiness. I come to the ghetto, do

not go in through the

gate, but

through the back way, on the side of Dunovich’s fence. Big Tiska, a

wall-builder encounters

me. He says:

‘You were led out of here this morning, how is it that you are

coming here?’ I say: ‘The

camp

commander sent me to bring back wood for the kitchen.’ In the

meantime, I grabbed a

neighbor of

mine, Litwinsky, with a horse and wagon. He tells me that he works

in the city council,

transporting

things from the ghetto. I give him 30 marks for him to transport a

bit of wood for me.

The gentile

permitted himself to deal. I entered my own home, and began to pack

up some things

with which

to cover myself, grabbed a blanket, a bit of underwear, a couple of

towels. More to the

point, I

wanted to take some pots, bowls, plates. And this was mostly to be

retrieved from the street.

Also, I

found small sacks of food, that the peasants felt was not worth

taking away, lying in the

street. I

filled a wagon with pots and pans and utensils, with kasha flour,

with everything that came

to my hand.

On top, over all of these things, I put wood that the gentile

through out through the gate;

I went out,

the way I came in – through the back way. I went into a bakery, and

bought ten old loaves

of bread,

literally dried out, for which I was charged a high price. With

everything loaded onto the

wagon, I am

now traveling with a great deal of merchandise. I had made up with

the gentile, that at

the gate, he

should say that he was sent from the ghetto for the Jews, with me as

the interpreter. And

that is the

way it was. I said that I was coming from the forest, and that the

bread was for my family

in the camp.

With luck, I got through the first gate. And they then permit you to

go on further,

because they

know that there is no way back. I ride over to the third block. I

was greeted with great

astonishment

and tumult; from whence did I bring all of these things? Previously,

I had not entrusted

my great

secret to anyone, so they would not know what I was thinking. I

recall the elderly

Chaimsohn

falling upon by neck and beginning to kiss me.

When the

wood was taken down from the wagon, and they saw the pots and pans

and utensils, there

ensued such

a melee of grabbing, that if I had not grabbed a pot for myself, I

would have been left

with

nothing. Also, all the sacks of food were taken up, but the people,

afterwards, brought back part

of it for

me. On that day, I brought life back into that block, and one could

now see people standing

by the

kitchen with plates and pots.

On that day,

Donkland, a man from Zambrow, approached me, who had been a former

police-lieutenant in the

ghetto, and wearing an official armband in the camp, and he asked

me, if I wanted

to come and

live with him in his room, designated for a couple of families,

since it was within his

discretion

to pick whom he wants, and since I am a ‘sidekick’ he wants to

include me in these couple

of families.

I was taken into this room with my mother. We got a corner, and in a

couple of days

time, my

brother Yankeleh arrived in the camp.

They were a

few tens of Jews near Sendzjawa in a barn on a field (also Chaim

Kaufman was in this

group). The

Poles turned them in to the German gendarmerie. From that time on,

Yankeleh was with

me.

XIX. The

Bread of Hunger

Life in the

camp got progressively harder and harder from day to day. The little

children that were

with us,

began to die off. Also, our child, who remained after my brother

Moshe & Sarah Bronack,

died. The

typhus epidemic grew more intense, spreading death and desolation

around. A sort of

hospital was

set up, in a large and cold barracks. Using straw as the bedding,

like in a horse stable,

and covered

in rags, the sick expired from the cold, in pain, and agony beyond

human capacity.

It was the

months of November-December. Tortured by hunger, strategies were

sought for how to

get bread

brought in from the outside. Those who have survived must surely

remember how we used

to drain the

effluent from the latrines in the barracks, and take it away in

large barrels as the refuse

with which

to fertilize the fields. It was believed, as previously already

mentioned, that it was this

waste

material that was the cause of the typhus epidemic in the camp.

Using these very same barrels,

the carriers

of the typhus plague, they were employed for smuggling bread into

the camp. We struck

a deal with

a certain gentile, a latrine worker, that on the way back from the

field with an empty

barrel, he

should fill the vessel with a sack full of bread loaves for the

camp. We paid for the bread,

with gold

and precious stones, which not only once, had traces on it of having

been in that barrel.

We literally

fought with one another, almost like a war, for this bread. And

indeed, this war led to

the

revelation of this ‘conspiracy.’

The Germans

would never have thought that these vessels would be used to conceal

food. And when

the fighting

broke out in the camp, an open war, the Germans investigated, and

discovered the reason

for it. They

beat up the latrine barrels, but there was no one that was willing

to take the cover off the

barrel and

stick his head inside – well, the Germans then used long tongs

????...

There were a

group of ‘toughs’ in the block that wanted to seize the ‘monopoly’

over the bread. The

police in

the block oversight were partners in this endeavor. On the other

side, stood people starved,

totally

spent, furiously impelled to buy a morsel of bread for themselves.

Who were these ‘toughs?’

The

ringleaders were Arky and Barky. The police had to get involved in

order to make a

compromise:

on one day, the ‘toughs’ will get the bread, and on the next day –

the remainder of the

block.

About the

camp, there straggled people who were mere shadows, who begged for

their own death.

The block

became infested with lice. The lice crawled all over the clothing,

those items that were

already

worn, but had to be worn during the day, and slept in at night. With

the coming of the day,

some of the

clothing was taken off, first the overcoat, and put out on the snow,

in order to freeze the

lice. This

aired out coat was then put on again, and some other part of the

clothing was taken off to

be frozen.

XX. The

Lomza Refugees Plan to Escape

The Lomza

Jews had organized themselves to plan a breakout from the camp. And

one out of every

ten of the

group volunteered to crawl through the barbed wire, and to reach the

fence. The post watch

opened fire

on them, but nobody was hit, and the group escaped. At a second

time, a group of

Zambrow and

Lomza residents also attempted an escape. Once again, they were

fired upon.

Shmulkeh

Golombeck’s son who had blundered into the barbed wire, and was

wounded, was

captured,

this being the younger one from Dobczyn and another young man from

Zambrow, whose

name I do

not remember. The third one captured was from Lomza. The

executioners carried out their

vengeance in

a very basic way, in front of the people as witnesses. All the Jews

in the camp were

driven

together on a large plaza, and the three young boys were brought

there, one of them crippled

in the feet.

Four S.S. troops stepped forward to do whipping, holding nagaikas.42

All three were

stood up,

and one after another, were whipped with the braided nagaikas. Two of the beat them as

if they were

threshing wheat with grain in them, and each one was given thirty

lashes. After the

whipping,

they were taken to the hospital and they died there.

I had

previously told that the peasants used to provide potatoes for the

camp. Two of the young men,

who has

gotten away in the first escape, from the Lomza group, bought a

horse and wagon, and

brought

potatoes, pretending to be peasants. Hidden under the potatoes, they

would smuggle meat,

butter, and

other sorts of foodstuffs. Young men, from Zambrow and Lomza, worked

in the

commissary

of the camp, and they knew how to conceal these provisions. One time

the boys dealt

with this

stuff in an unguarded fashion, perhaps out of too much confidence in

themselves. They

came into

the camp with a wagon load of potatoes, at a time when there was no

one else with them,

real

peasants. The guards inspected these ‘peasants’ and they were not

satisfied. A patrol was sent

after the

wagon. An investigation and search was conducted in the wagon, and

they found what they

found. For

this crime of bringing food to the hungry, the Germans sentenced

these two young men

to death.

They were hung in the barracks. If I am not mistaken, they were

called Itzik and Yudkeleh.

I knew them

from the labor camp at Szumowo. We were there together, both people

from Lomza

and Zambrow.

Once again,

all contact and dealing with the outside world was broken off. We

literally expired from

hunger.

Death hovered over our heads.

The dead

from the camp were interred in the Zambrow cemetery. There was a

small wagon in the

camp, on

which, day-after-day, the dead were placed, and under watch, taken

to the cemetery. The

graves were

dug to a depth of forty centimeters, and lightly covered with the

earth. On the way back,

usually we

bought a bite of bread, onions, and potatoes from the residents that

lived beside the

cemetery. On

time, Schaja Henoch’s son-in-law came along. He stepped away from

the funeral

procession

to buy bread. When he returned, the soldier shot him. He was shot,

and we were ordered

to bury him

immediately. People told that when he was lain in his grave, his

still showed signs of

life.

XXI. The

News

It was the

middle of December, 1941. Seeing that the typhus epidemic grew more

intense, and people

were dying

on a daily basis, either from typhus or from hunger, the commandant

of the camp, on one

day, called

our representatives to him and said to them as follows: ‘I see that

you are all going to die

here, and I

have decided to convey you ‘further to the east,’ near Odessa. There

you will work and

remain

alive. Here, we have no work for you. Tell you brethren, that they

should comport themselves

quietly and

in an orderly fashion, and we will deal with them in a good way.’

When the

representatives came back to the blocks, and relayed the news to us,

there was no doubt

in any mind

that this means – Trebl inka! The exhausted ones were shaken, and

the spirit of

rebellion

rose in the blocks. This was true with the people from Zambrow and

Lomza, as by those

from

Tshizeva and Wysoka. Voices were raised that said: ‘We will be

killed here, but not to go to

Treblinka!’

Talk began about a rebellion. With bare fists, however, nothing

could be done, and there

could be no

talk about having arms and ammunition. And even, at the price of

hundreds of victims,

we were to

break through the gates, where would we go? We had already fled once

– and come back,

or having

fallen again back into German hands.

XXII.

Glicksman Feigns ‘Making an Effort’

As we

understood it, Glicksman, along with the senior from Lomza,

Mushinsky, again made a deal

with the

camp commandant. Now the commandant no longer spoke of Odessa, but

only about a labor

camp. I am

not certain if he actually called out the name of Auschwitz. At this

time, that name was

not familiar

to us. The commandant said that in this labor camp there were

factories, and he

promised

that we will have the same seniors and leaders there. That is what

was communicated in

that hall,

that after long negotiations, that Glicksman engaged in, that we

will not be sent ‘to the east’

but rather

to a second camp.

XXIII. The

Preparations for the Trip

life has

become repulsive, and it is not possible to continue this way!’ –

You could hear this in every

conversation. People, who were half-dead, for whom there are no

words to describe their misfortune,

gave up on

everything, making peace with their dark fate. In the meantime, news

reached us, all

manner of

rumors. First the Lomza block would travel. The transports will

depart by night. The

extraordinary situation will be clarified. The people in all the

other blocks will remain confined, not

even

permitted to stick their heads out from their confinement, and it is

forbidden to light candles.

Between the

eighth and the tenth of January 1942, the ‘work’ began. In the

middle of the night,

movement

began in the first block. Immediately short shots were heard, and

there was no lack of

victims. The

same took place on the second night, in the second block. And now

comes our turn:

block number

three. I think it was about eleven o’clock at night. A fresh newly

fallen snow shone

in the

window with its pristine whiteness. We began to drag ourselves out

of the barracks to a rear

gate. There

was a deathly silence all around. We felt like we were going on our

last walk. No one

brought so

much as a word to their lips, as if everyone, simultaneously, had

turned to stone. We go,

and fall in

the snow. One person helps another. Each one has a pack on their

backs. On the other side

of the gate

there was a long row of sleighs and wagons waiting for us. One way

or another, we got

on board.

The entourage moves. There are a hundred sleighs and wagons. I was

among the last. I am

not among

those who are in any hurry. It didn’t matter to me if I was the last

one to die. We are

traveling in

the direction of Tshizeva, to the train station. On the way, once

again, I spoke my

thought out

loud: ‘Perhaps we should flee?’ My mother was silent and didn’t

utter a word. This time

she didn’t

say ‘yes’ and not ‘no.’ She was mumbling with her lips as if she

were reciting the

Tehilim.

Yankeleh

said: ‘I no long will flee. I have nowhere to flee to. The Poles

drive you out, turn you over

to the

Germans. There is no Jewish settlement. Where am I going to go?’ I

myself lacked nimbleness

on my feet,

and I had decided to stay with my mother. And Yankeleh added:

‘Whatever happens to

you, will

happen to me.’ And so we traveled. The road was strewn with frozen

people, who had

fallen off

the wagons. Sleighs came up from the rear, and collected them. I

will never forget this

terrifying

trip.

XXIV. On the

Train Station at Tshizeva

Dawn began

to break when we arrived at the Tshizeva station platform. A chain

of about 50-60

freight cars

stood there. We were driven across the icy stretch. Those who were

frozen, were dragged

by the head,

and the feet, and thrown into the wagons. As to the living, about 50

were crammed into

each car,

and the doors sealed from the outside. And this way, we stood and

froze for long hours. In

the end, the

train moved. After riding for a couple of hours, we again remained

standing. We are

expiring

from the cold, oppressed by hunger and thirst. We lick the ice from

the rivets on the sides

of the

wagon, that had grown up on their large steel heads.

In my car

were: Velvel the Fisher with is wife and little daughter; Elkeh,

Meir-Yankl Golombeck’s

daughter

with children. We still harbored the thought that, despite all, we

were being taken to

Treblinka.

When we arrived at the Malkin station, and the train stopped there,

a frightful panic

immediately

broke out. We knew that from Malkin, one rode into a forest, and the

distance is not

more than

from ten to fifteen minutes a ride. Velvel’s little daughter began

to tremble and spasm

over her

entire body, and she screamed that she did not want to die.

Following here, everyone broke

out into

bitter wailing. I sat stonily in a corner, and looked at my watch.

Five, six, seven minutes...

ten

minutes...fifteen minutes. We are proceeding to travel further. Who

can convey the agony of that

moment.

‘Yes’ – Velvel says to me – ‘Glicksman didn’t deceive us after all.

Indeed, we are not going

to

Treblinka, just as he said.’ Velvel, who belonged to the police

staff, knew Glicksman and his ways

well.

XXV. Not to

Treblinka!

We are happy

with our newly won life. Not Treblinka, well, then it can be

whatever it will be. And,

lo, once

again we remain standing at a station platform, parallel to our

train. My Yankeleh sticks his

head out.

‘Yitzhak, it is a military train,’ he says to me. And the kitchen

stands exactly diagonally

opposite my

little window. Since Yankeleh ad worked for the Germans, he spoke

German quite well,

and so he

says to the cook: ‘We are refugees, can we ask for something to

drink?’ The cook says:

‘Give me a

pot, and I will give you coffee.’ I had a small bowl with me, that

we used as a urinal in

the train

car. It was quickly wiped out, and Yankeleh stuck it out between the

grating on the little

window, that

went up and down, and in the blink of an eye, we had a bowl full of

black coffee (at

the time

that the bowl was on the way from the kitchen to our little window,

a soldier shot twice in

that

direction. However, the bowl came into our hands intact). We divided

the coffee by drops, and

everyone got

a taste of it. We were happy: not Treblinka, and to that, we even

got a bit of black

coffee –

well, there must be a God in heaven! But this joy did not last for

long.

After two

days and two nights of travel, we finally came to a junction. Taking

down the covering

from the

grated window, we saw a lit up area with large excavation machinery.

The snow had

covered

hills and vales. These were the chambers of Birkenau, Auschwitz.

And if so,

are these the machines used to dig graves? Is it here that we will

come to our eternal rest?

Meanwhile, a

variety of ideas came to us. Velvel says: ‘If they let us take our

packages, this will be

a sign for

life; and if, God forbid not – it means that we need nothing

anymore, it will be a sign of

death.’ We

hear a noise, and it sounds Jewish. Yiddish is being spoken. What a

joy, we are among

Jews. A

wagon platform arrived with pickaxes and spades, Several tens of

people in pajamas, who

speak

Yiddish, led by Germans in uniform, and it was about midnight, going

from Friday to

Saturday.

They immediately went to work. The locks on the doors were covered

with ice, and they

were hacked

apart with the pickaxes. They began shouting ‘Everyone out! Everyone

down!’ They

began to hit

us with batons over the head. In a minute an entire movement

started, and an alarm

broke out.

Around us,, there stretched a long line of freight trucks, covered

in black brezenten ???

We hear the

command: ‘Into the trucks, up!’ The unloading was hellish, like out

of a nightmare. You

immediately

saw a pile of people. Frozen, fainted, half-dead. And I saw one, who

had pulled his

overcoat

over his head to protect against the cold, and he was beaten with

batons, and thrown onto

the huge

pile of people. Another command: ‘Women separate! Men separate! To

the Trucks!’ And

the freight

trucks are soon overfilled. I remain with my mother and brother,

locked and impoverished

in the great

trap. We see how men and women are picked off. They are set out in

rows of five. The

job of the

selection was being conducted by German officers. A significantly

large number were

picked out.

The Germans don’t let anyone through. We see the way people tear

themselves away to

come into

the ranks of those selected, and they are driven back. And here my

mother said: ‘Run

children,

maybe you will be able to save yourselves.’ We exchanged kisses with

our dear mother.

She remained

standing with outstretched arms, and tears were flowing from her

eyes. In a moment,

we no longer

saw her.

We get

closer to the row which is very strongly inspected. The big German

shouts at us: ‘No more

room,

locked!’ We force ourselves over to him. We present ourselves

anyway. He takes us in with

a glance.

Two handsome young men. He asks me: ‘ What is your occupation?’ I

answer:

‘Construction workers.’ And Yankeleh says: ‘ I am a gardener.’

‘Remain here!’ the German says.

And in this

fashion, we were the last two who had the privilege of being in that

group.

When we left

that place, dawn had already begun to break. God had begun to look

down upon his

great

handiwork. On the killing field, the mountain of the dead, frozen,

beaten, and half-dead

remained.

They waited for new freight trucks to arrive and take them away,

because they could not

walk under

their own power. I remember that Chaim the Harness Maker wanted to

push himself into

that line.

But everyone had received the order to lock [arms] and not let

anyone else in. Pitiably, all

he got was a

whack in the head with a baton, and he was driven away. A minute

earlier, before the

lined were

closed, Bendet Fekarevich the watchmaker smuggled himself in. We

begin to march. That

is, those

Zambrow Jews able to work, approximately a hundred in number. What

the number of the

women was, I

do not know, but I gathered that it was much less. The remaining

Jews of the Sacred

Congregation

of the Jews of Zambrow, were killed that same night in the gas

chambers.

XXVI. The

March to the Birkenau Camp

The march

began with beating and kicking, with pushing and hitting with clubs

and rifles. We came

to a large

tent. We were taken inside, and turned over to the hands of the camp

people, dressed in

pajamas.

This was the

dress in the camp. We were arrayed in two rows. Those who were

occupied with us,

were Jews,

big, strong young men. They shout like the Germans, and also hit

like the Germans. My

Yankeleh

says: ‘See, it is possible to make a German out of a Jew.’ One, the

senior among them,

gives his

speech. The first greeting was accompanied by a hail of curse words.

listen up! Do you

know what

Auschwitz is? You came here by yourselves, you were brought here in

chains. So, damn

your father!

Turn over your dollars, gold and precious stones. If any of these

things are found with

you after

the bath, he will go directly to the ovens. That is a ‘K.L.’ ‘Kein

Leben. 43’

You go in through

a gate, and

you go up to God through the chimney. You understand, that here, you

need nothing!’

He goes

through the row this way, stops at an individual and asks: ‘What,

you are not pleased?’ –

raises his

hand and delivers a hard blow to the face.

A blanket is

spread out – and immediately a sum of money fell on it, along with

watches, golden

chains, and

rings. Who could take the risk of trying to conceal something

valuable on his person?

After this

welcome, a number of us were granted a small dish of hot kasha. In

this time, less robust

five or six

men had fallen down from lack of strength, lying by the door,

lacking the strength to get

up on their

own. After eating, the procedure began of etching us with a tattoo

number on the arm.

when this

was over, we were told we would be taken to bathe.

XXVII. Into

the Bath!

They lead us

out of this barrack and bring us to a second barrack. This is the

location of the baths.

We are given

the order: ‘Undress!’ To strip naked, immediately outside at the

entrance to the

barrack. We

strip off our lice-filled, but warm clothing, and we stand naked as

the day we were born

in the

frosty outdoors. ‘Wait a bit, another party is bathing right now.

They will come out soon.’ We

wait this

way for about a half an hour, frozen, contracted from the cold. Our

clothing was cleaned

off.

Finally, with luck, we are going into the bath. Barbers were waiting

for us with hair-cutting

machines,

and they took to us, to shear off the hair from our heads. After the

haircut, we went and

stood under

the spigots. Water is pouring onto us, water as cold as ice. A

number of us first take to

having a

drink. Imagine if you will, how great the thirst was, that oppressed

us.

After the

bath, we were driven to a disinfection station. We were made to sit

on benches, like in a

bath house,

no comparison intended, and released a bit of steam onto us. After

this, regardless of

how wet we

were, we were driven into yet another large barrack. Here, we were

allocated clothing.

‘Fall out

into rows!’ – the order was given. And again a speech, with the same

theme: ‘anyone who

might steal

an extra shirt, or a legging for the feet, will immediately go into

the oven!’ Shirts are

given to

some, drawers, pants a jacket, a pair of shoes with leggings.

Shivering from the cold, we

donned these

rags. Some got three-quarter trousers, others shoes, that could

barely be put on the feet.

There was no

covering for the totally shorn heads.

Now, Polish

guards take us over. We are told, that we are going to Block 21.

Again, we stand,

petrified by

the cold. under an open sky. We wait until everyone gets dressed.

XXVIII.

Block Number 21

Finally, the

‘party’ begins to move. We wind through, in a serpentine path,

through small streets of

barracks. We

come to Block 21. ‘Remain standing!’ – the block senior orders. We

remain standing.

And another

order: ‘Undress, and enter the block one at a time!’ We undressed on

the snow, and we

waited. We

are allowed in, one at a time. I happened to be among the first.

Inside, near the entrance,

there was

the camp doctor, not a German. He begins to examine me. As

previously mentioned, I

wore a

bandage on my right foot. I had already torn off the lower part of

it, but the top part still

adhered to

me, even to the point of having melded with my skin. ‘What is this?’

– the doctor asks

me. I

explain to him that I received a blow to my leg, when I worked for

the Germans, and this was

put on me

then. He asked me to sit down, and to raise myself fifteen times,

and when I did this, he

let me

through. And this is how several went through the examination, and

if someone displeased

the doctor,

he made note of the tattoo number on his arm.

Now we go to

sleep. The bunks are concrete, with five people to a compartment.

And on the concrete

there was a

blanket and two coveralls. We arranged ourselves on the hard bunks,

and immediately

fell asleep.

[After] a couple of hours of deep sleep, and they are shouting

already: ‘Get up!’ We tear

open our

eyes, and bandits are already standing there with irons and shovels

and they are banging

on our feet.